So, what exactly do Kickstarter campaigns do to reach that coveted 100% funded milestone? For starters, it’s all about the pitch. A long while ago I had heard that in order to capture the majority of your audience that you need to grab them within the first 30 seconds of the video and that most don’t read the text below a few paragraphs. Unless you’re someone like me who reads every line of text, watches every video posted, and combs through every comment and update you probably skim through the main page at best. People lose interest fast and successful projects take advantage of this.

And communication is also key. Those that want to drum up interest need to stay in touch with their backers. Whether it’s by having discussions in the comments, posting regular updates, or just listening to fans’ concerns and suggestions this dialogue between creator and backer is essential to keeping up the momentum. I’ve seen some, particularly the Precinct and 7th Guest Kickstarters, not just fail but peter out very early on never to pick back up. Both failed to listen to backers’ suggestions and advice and both tanked miserably.

One of the biggest differences between Kickstarter in 2012-2013 and today is in what the developer has to show for themselves in regards to what they’re pitching. Gone are the days when a Tim Schafer or Richard Garriott can say “Hey, I want to make a game, I have a basic idea but nothing to show. Throw your money at me.” These days projects need some assets to show off, whether it’s as part of a series of videos or an actual playable demo. Few people would go in by brand recognition alone now unless they’re hardcore fans. And even then most of those have to have a track record of making good games.

And then we have the “asking price”. How much should a Kickstarter campaign ask for in order to (hopefully) assure funding? Back in 2012 it wasn’t unheard of to ask for several hundred thousand dollars or even in the millions and it could still get funded, usually pretty easily (like in the first several hours or even days) with plenty of time to knock out stretch goals. Today you’ll be lucky to see a few tens of thousands of dollars (or local equivalent) in any given indie game. And even then it’s hardly a sure bet. Sometimes even just asking for $10,000 is an uphill battle with so many other projects vieing for your hard-earned money.

One of the major issues plaguing game developers today that want to go through Kickstarter is an over-saturation of titles that seek funding. There’s hardly a moment when some game or another is looking to the fans and potential fans for money. There have been several times in which I was backing at nearly a dozen projects at a time and I either had to pick and choose what to keep or to lower my pledge considerably to be able to help them all. One sad reality with this glut of games is that lately it seems like most either don’t make it, have to cancel, or barely make their base goal. While there are some exceptions to the rule, such as the recently launched Tokyo Dark, quite a large percentage struggle throughout their month-long cycle. Several have had to outright cancel because of the lack of interest for some reason or another.

And making games is costly and time consuming. There are tactics that some developers take when going through Kickstarter. The most common that I’ve seen is to basically gut it to the base game and then re-introduce content in as stretch goals. By doing this, they can ask for less money. Which in turn makes it easier to reach 100% funded without sacrificing too much in return. Sometimes too much can be found on the cutting room floor but by putting concepts back in piecemeal as stretch goals they’ve at least (usually) secured some money to continue development. Sometimes something is better than nothing.

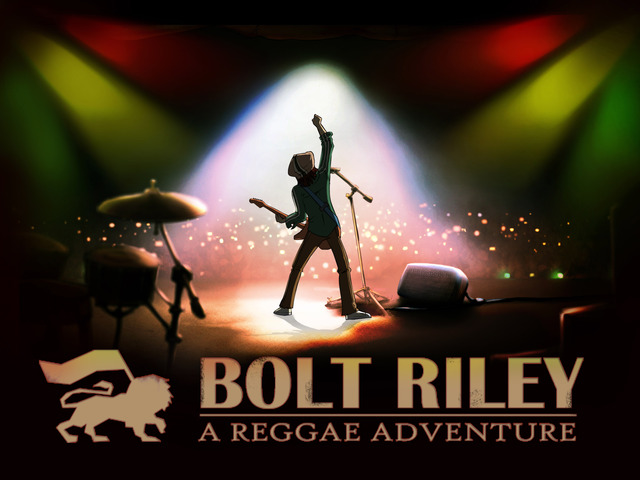

Another tactic that is growing in popularity is to offer a game through Kickstarter in “episodes” or “parts”. Generally this is done by campaigns that didn’t make it the first time around but still want to have input (and money) from backers. A good example of doing it this way is Bolt Riley. Initially they wanted to do a full game but had an incredibly hard time getting funding the first time out. A second attempt was made for just the first “chapter” and due to the lower funding goal managed to make it before time ran out.

At the end of the day the main driving force of any successful Kickstarter campaign is the backers. While a developer can have the best pitch in the world and the proof that they can pull it off, an idea won’t take off without others spreading the word. Sites like Kickstart Ventures and Cliqist that specialize in spreading the news about interesting and unique game ideas help a lot, but a good deal of the legwork is really done by the rabid fans that want to see their favorites succeed. Between social media and word of mouth the ones that do the best are the ones that are talked about. And to do that you need to capture your target audience.

Tokyo Dark was out their with what it wanted to present quite early on square collective. It was exceptionally visible and having square enix support at their back was pretty noticeable.

And that’s one of my points. It’s usually the high profile Kickstarters that get funding either right out the gate or within days. And I’ll be honest here. I didn’t even know about Tokyo Dark until my contact in the Collective messaged me about it.

Dear, i think there is one point you’re missing in your article (but you can’ talk about everything..). Sometimes it’s not about the pitch, the lack of demo, screenshots, presentation, i’ve seen perfectly presented project with everything in it fail (nice reator active and all) and i’ve seen horribly managed campaign (like little devil inside) been funded.

I think, it’s also a question of demography. In 2012 KS was in boom and the number of backers was growing exponentially, i don’t have the actual data but atm the number of new backers must decrease and more importantly the number of returning backers are decreasing. This is mostly due to how badly campaigns that have started in 2012/13 have gone wrong in every aspect possible and disappointed old backers (concept of whales also like you and me that are attracting people..and pledge a lot) and scared off potential new ones.

The list is long, between double dipping, scam, revoked exclusivity, broken games, unfinished games..etc..But the worst part is seeing a game you backed support waited being sold at lower cost than you paid for (including your goodies in DLC package). It’s not about the money, it’s rather when it happens you’re thinking “it’s not worth the wait..” and the potential backer who can have it this way think “what’s the point in pledging? I am no fool”.

Ultimately how badly the backers are treated by the creators will be the doom of this system. Which is why i think creators should find other ways to rewards backers by offering them things you wouldn’t get on a SEA (Beta & Alpha) or in DLC’s.

You’re absolutely right in all your points. Unfortunately, there’s only so much I can talk about in one article before it becomes way too long. This one (and pretty much all of my theorycrafting articles) are already double-length based on standard word count. That said, I’ve been dealing my thoughts on crowdfunding piecemeal. I could make this into a regular (or semi-regular) series.

I know, it’s a shame about the length though. This is really the kind of article i’d love to read more extensively.

“Between social media and word of mouth the ones that do the best are the ones that are talked about. And to do that you need to capture your target audience”…I completely agree with this! If people don’t get excited and spread the word, nobody will show up and back the projects. I do feel in some ways the Kickstarter bubble is floating in the background and whether or not it pop’s is up to the community.

P.S. There needs to be some bang for their buck, if developers expect crowdfunding cash, they need to offer something worth the risk; especially considering the bad reputation Kickstarter has picked up this last year.

Yes. Exactly. People generally don’t back projects purely out of the kindness of their own heart. Even I need a carrot dangling on a stick in front of me most of the time. At least to get me to pledge higher than a digital copy of the game.

[…] makes your project weaker. The best example I see time and time again, are developers who post stellar campaign pitches, only to ruin them with bad gameplay […]