The Retro VGS has been making its way around the gaming scene for over a year now in the idea stage. Since its earliest unveiling by mastermind Mike Kennedy, a variety of indie developers have pledged they will bring their titles to the fledgling modern-retro platform. After all, in many ways, the concept is awesome for those of us who feel a bit fed up with the modern state of games. For example, when I get the urge to play something, I’d like to play it at that very minute. Although digital downloads run mightily fast on my connection, video game downloads are increasingly huge. There’s also the matter of patches and frequent firmware updates which means it can take anywhere from 5 minutes to over an hour before it’s finally possible to play anything.

The Retro VGS proposes an answer to that problem. It also brings a lot of nostalgia with it. One of the focal tenants is a complete and total lack of firmware updates and downloads. Instead, games just are pressed onto cartridges and ready to go. Outside of portable devices such as the PlayStation Vita and Nintendo 3DS, we’ve not seen cart-based media on home consoles for years now. In that sense, it also proves a mighty fine appeal to collectors who adore physical goods. The Retro VGS has gained its share of verbal praise over time, but that praise alone wasn’t enough to get it to succeed on Indiegogo.

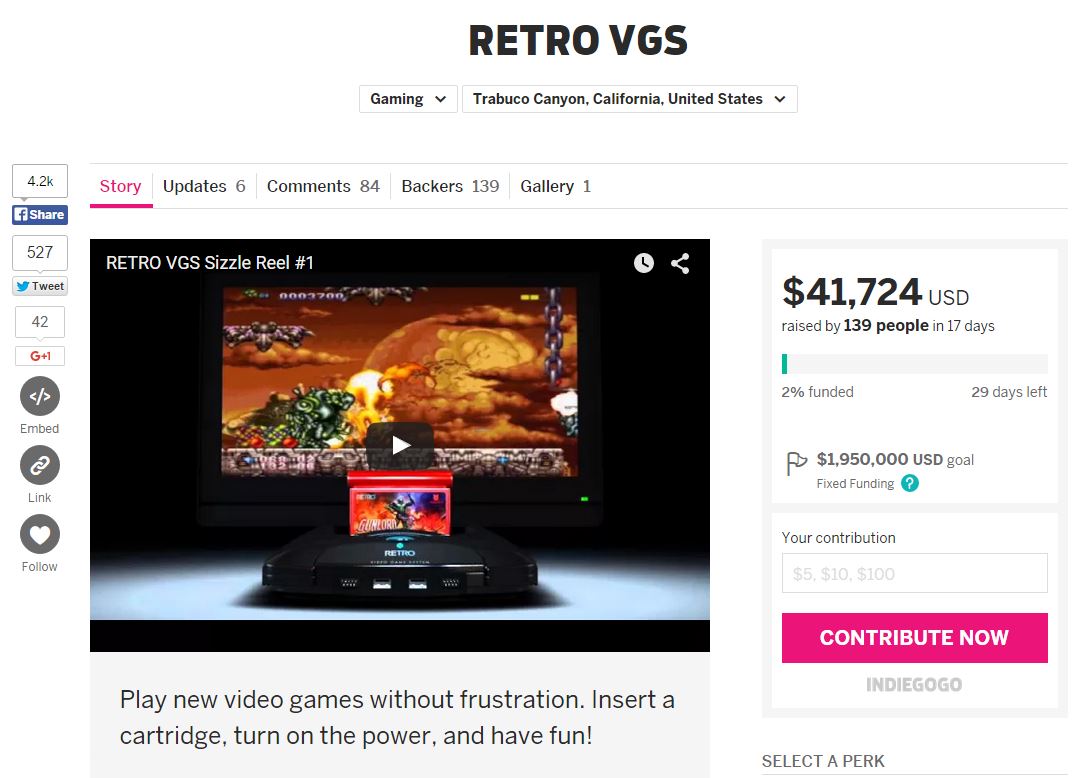

As you may have heard, the Retro VGS crowdfunding campaign has been canceled due to totally stalling out at just under 150 backers. Those backers were apparently immensely into the project as they managed to raise over $40,000 with such a small group. The question that some are now asking is why didn’t this project make it? Why was a certified retro enthusiast console unable to attain a goal of $1,950,000 when something like the Ouya managed $8+ million with just a fuzzy idea? It’s impossible to know for certain what all went wrong, but I certainly have my suspicions about what may have played into this Indiegogo failure.

I’m a bit of a physical game collector. Over the years I have amassed far too many games alongside an unhealthy amount of consoles. My interest in collecting is so vast that I’m even willing to buy systems even when I own absolutely no games for them! It’s just exciting to own bits of gaming history — even if it’s not kind to my wallet. That was the main reason I took interest in Retro VGS. It had nothing to do with playing modern indie games on a cartridge. As unique as the idea is, there are already tremendously many avenues to play these titles (both on PC and portable and home consoles). The novelty alone isn’t that big of a motivator for me and I assume this was also the case with other collectors.

Then there’s the question of expense. Sure, the system alone was set to retail for $349, but that’s just one portion of the equation. Collecting the actual cartridges is something many collectors had in mind, due to our habit of sometimes seeking to “complete” a set for a given console. On one hand, I was intrigued by the idea of maintaining a complete set of Retro VGS games. Due to my cautious nature, I viewed the system from the perspective that it probably would never see a tremendous amount of game releases despite early support. As such, it wouldn’t be a super expensive library. There’d still certainly be an expense, though.

But how much would these carts actually cost — and who would be the manufacturer? Would Retro VGS itself pay for fees to produce a bunch of carts per game or would it be on the indie developers to fund it themselves? If the latter, that would almost certainly destroy the potential of many releases because most small teams don’t have that kind of money upfront. No matter the situation, it would likely yield a higher sticker price when carts finally rolled out for sale. A penny over $60, though, would almost certainly cut out most modern gamer interest outside of for the most famous of games. For example, even those without a Retro VGS would probably pay big bucks to own Shovel Knight on a cartridge.

Let’s look more into the viewpoint of modern (not necessarily collectors) gamers. What about from the viewpoint of non-collectors? It seems an even bigger niche with a harder hurdle to surpass. After all, many of today’s gamers thrive on digital media. And when they don’t, they still are aware of the purpose of patches and accept their presence. As we’ve seen from infinitely many big budget releases over the past few years, video games are rarely ready for prime time on launch day. It’s a disturbing trend but one that seems here to stay. On that token, it sounds almost like the Retro VGS is a savior. But that’s not actually the case.

Just think about it — Many indie releases are also plagued with bugs and see themselves patched a handful of times. We just don’t tend to hear about it as much because it’s far more of a headline to say something about the newest Batman game being a glitchy mess. Indie developers often have fewer resources for bug testing than the big studios, unless they have a swath of Kickstarter backers to play through an alpha. As such, the promise of “no patches” is one which many rightly predicted would become an issue almost immediately. In theory it sounds amazing, but the reality can’t prove as positive.

The Retro VGS is not gone forever. As was stated in their last backer update, they’ll be coming back to crowdfunding in the future. They just recognized that their project simply wasn’t going to make it right now and that a reduction in costs was required first and foremost. I applaud them for trying with an honest goal value but unfortunately the nature of crowdfunding rarely works this way with big projects. For the most part, we see projects severely undershoot their actual costs.

Luckily for them, the most exciting quickly draw attention and gain far over what they actually asked in funding. The path to success is securing yourselves, hopefully overfunding to an immense degree, and then obtaining outside investment once your idea is a proven success. Given the right attention, the Retro VGS has the potential to succeed, though it is too niche to reach the team’s current expectations.

Been following the project and i had a lot of issues of it . Firstly was originally supposed to be $150 and on kickstarter then it changed to $299 and on indiegogo and i heard kickstarter requires a working prototype and indiegogo does not.Next i really do not know many developers who would want to commit to a niche cartridge projects and make them exclusive.Then one of the people involved with the development of the FPGA left the project i think he goes by kevtris. Imagining getting a cart version of the game that is available for other formats but on the digital formats they release updates and free dlc like with shovel knight ….and the cart version unable to do that.

I think they should have really gone with a retron 5 style device that can run as many cart based console games as possible. And then have a usb port that can run games of usb stick so for example they can perhaps release a version of shovel knight on a usb stick so you get a physical version. And for those type of games i really cannot see loading times being a issue.

One of the many concerns I had with this was the fact that they went with Indiegogo. I don’t know exactly why they went that way, but in my mind it had to do with the fact that Indiegogo doesn’t ask that you prove you actually have a product before starting your campaign. Definitely not saying they’re scamming, but I’m under the impression that they don’t have a prototype (which is what would be required for Kickstarter).

And that was what was causing a lot of issues as later in the project someone who said they were working on the project said they did have a working prototype. And then on the main page they showed a “working ” prototype but showed very little as they say cannot show much for patent reasons as they have not got the patent for it. Now someone else did a video saying that does make sense as once shown getting a patent is hard but then again if it is a Retro style system chances are patents have all been sewn up long ago