Before leaving to join Arcade Distillery, Conrad Zimmerman worked at Cliqist behind the scenes as an editor. It was my idea, as Executive Editor (whatever that means) to bring him aboard, and Cliqist’s founder and Editor-in-Chief Greg Micek agreed. For those three months, Zimmerman helped guide the two of us, as well as Joanna Mueller who rose to the position of Editor shortly before he left, through the perilous waters of running a video game website. It was invaluable experience for me, and I dearly miss working him and speaking to him nearly every day. While we’ve lost touch since he left Cliqist, I still consider him a friend.

Humble Beginnings

Before that, Conrad Zimmerman was one of my idols in this industry. Since I first started writing about video games blogging on GameTrailers when I was 17, I followed Zimmerman’s work – and that of his Destructoid colleagues Jim Sterling and Jonathan Holmes – almost religiously. Podtoid shaped my humor into the limp, pathetic, unfunny nonsense it is today. Zimmerman’s borderline nihilistic, yet realistic, perspective was a great foil to the bloodhound, zealous work of Sterling and the light-hearted and fun nature of Holmes’ dopey articles about Nintendo.

So when we said goodbye to Conrad shortly before the start of Arcade Distillery’s Court of the Dead Kickstarter campaign, it was a bittersweet moment. I was sad to see him leave, and I knew we’d fall out of touch, but at the same time I was excited to see what he could do working on his first video game.

I’m Damn Good

The possibility that I wouldn’t like Zimmerman’s first game always loomed in the back of my mind. I wasn’t worried about not being able to divorce my personal opinions of him with his game – that’s my job and I like to think I’m damn good at it. I’m not even worried about what me disliking the game would do for our relationship. There isn’t much of one anymore, and Conrad isn’t the kind of guy to dislike someone for speaking ill of his work.

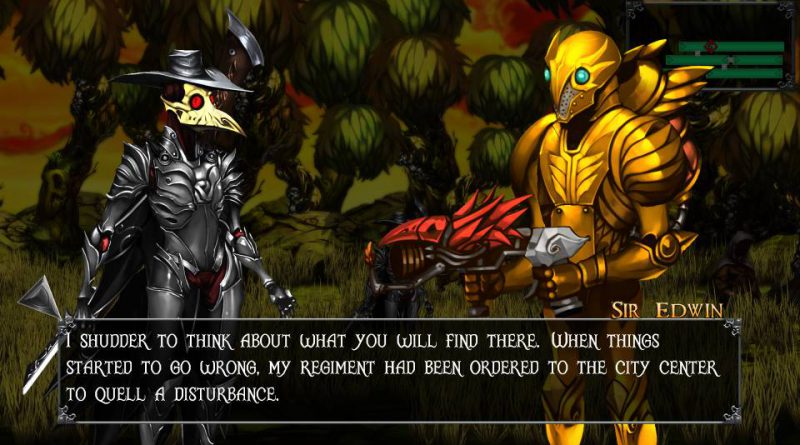

What surprised me was the depth in which I didn’t like what ended up being his first game – Plague Road.

I played Plague Road at an interesting time. Months ago, after temporarily leaving Cliqist, I thought my writing career was over. Then I picked up Jason Schreier’s book Blood, Sweat, and Pixels, a book that explores that process of making video games. There wasn’t anything too surprising in the book, we’ve heard stories about the grueling work it takes to make games for years now. But it still opened my eyes to how universal that slog is and just how much of a slog development can be.

Plague, Guts, and Colorful Art

I began to look at Plague Road as it if were a subject of the book, combined with my limited knowledge of events behind the scenes and my relationship with Conrad Zimmerman. I’ve never taken joy in ripping a game, so trying to deconstruction Plague Road as a way of trying to figure out why I disliked it ended up being a fascinating process, and some of that made it in the video above.

Some, possibly many, will say I’m in no position to review Plague Road. From Kickstarter to Release has never really been about reviewing a video game, it’s more about reviewing the process of a Kickstarted game from start to finish. Why was the campaign successful? Was the campaign any good? How much does the final game resemble what was in the pitch? What do backers think of the game? But if you think I’m compromised by my relationship, I won’t blame you. Maybe you think this article is terrible, and you’d like to deconstruct it the same way I deconstructed Plague Road. Or maybe you’ll start a coordinated hate movement against game journalism, both are equally plausible.

There’s a lot to consider when actually reviewing video games. Calling them “reviews” is silly. You review toasters, refrigerators, or TV’s. You review something to see whether it works or not, and if it does a good job at what it was made to do. But entertainment is so much more than that – it’s a living piece of work, you can’t just say if it works or not. You need to critique video games, and part of that critique, written by living human beings with their own biases, is taking outside factors into consideration.

What is Game Criticism?

I’m currently writing a Games of History episode about 1979 Revolution: Black Friday, a game about the 1979 Iranian Revolution. The developers of the game, most of whom are Iranian, were dubbed spies by the Iranian government. One even had to flee the country out of fear for their lives, all that simply for making a video game. The developers have also talked about how game developers are afraid to make games like this, that portray a real life event with complicated, deep layers and where there is no “good guy.” That’s exactly what 1979 Revolution is, a complicated game that shows a complicated real life event in a realistic way, without resorting to the standard video game or Hollywood trope of presenting a clear “good guy” to root for.

How can you not take all those factors into consideration when you talk about the game? They’re important factors that contributed to the final product, and they put the game in a unique place in gaming culture.

That’s the case with Plague Road. There are outside factors at play that inevitably play a factor one way or another: my friendship with Conrad Zimmerman gave me some insight on the behind the scenes production of the game (such as Zimmerman’s past interactions with Arcade Distillery’s founder, Luc Bernard, and how they weren’t trying to emulate Darkest Dungeon contrary to popular belief), which I thought about when reading Blood, Sweat, and Pixels, which got me thinking about the game’s Kickstarter campaign and the failed Court of the Dead campaign before it.

These are some of the things I think about when I made the above video about Plague Road. These opinions are my own, but that’s exactly what they are, opinions.