What is death? In A Mortician’s Tale, it’s a lot of things. It’s heartbreak, a respectable career, and an opportunity for profit. It’s as mundane as it is tragic.

[As well as death, content warning for discussions of suicide and transphobia.]

I, like most people, don’t like thinking about death. Forty-eight hours before playing A Mortician’s Tale, I was having a panic attack in the visitors’ bathroom of the assisted living facility where my grandfather is spending the last months of his life. So, yes, this game made me anxious. It made me squirm to carry out embalming procedures from the corner of my eye.

I also loved it.

A sense of mundanity

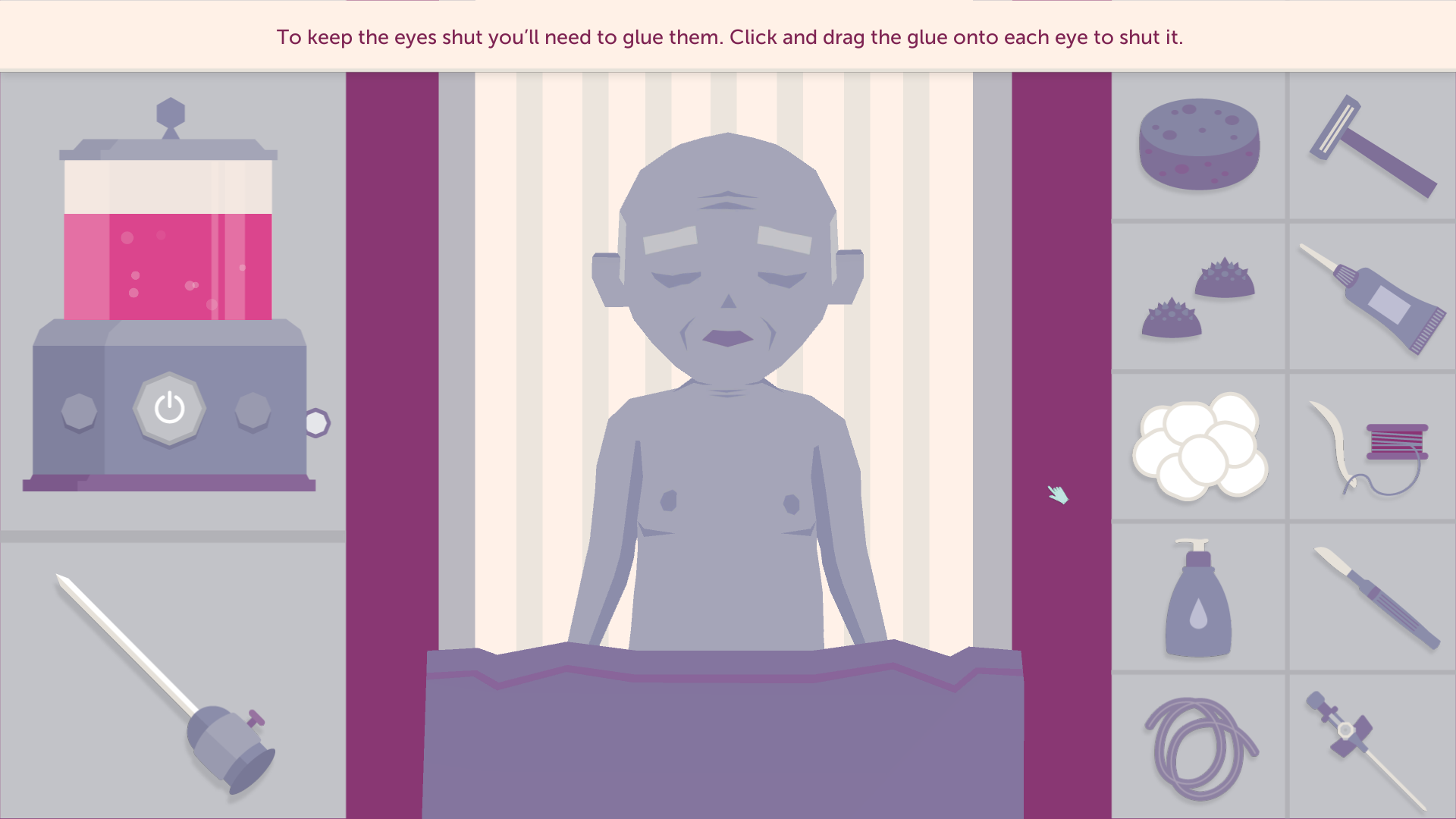

Death is a certainty. That means that, on some fundamental level, it’s mundane. Charlie, the game’s playable character, isn’t a Video Game Protagonist™. She’s an ordinary woman who prepares cadavers for funerals.

We only see her at work, but get a peek into her wider life via her emails; a back and forth with a long distance friend, plans for drinks with her co-workers, and so forth. These emails also tell A Mortician’s Tale’s overarching story. Caring for dead bodies and paying respects at funerals are regular, predictable moments in the game. They can provide education and reflection. Ultimately however, they are shown to be Charlie’s daily grind rather than being exploited for narrative drama.

That’s because it’s capitalism, rather than death, that haunts A Mortician’s Tale. Charlie’s employers, a mom and pop establishment called Rose & Daughters, are shown to be struggling financially and are eventually forced to sell out to a franchise. Contrasting the two approaches is how the game critiques the death industry – something it doesn’t shy away from doing despite its death positive intentions.

Choice and autonomy

Early in the game, Rose & Daughters is shown to be a genuinely caring business. They don’t just organise funerals to the family’s desires and budget, they point grieving customers in the direction of appropriate therapists and demonstrate a deep care for their employees.

In fact, the only real choice in the game comes from the concern that Amy Rose shows to Charlie. Most of the game plays out on rails; there’s no opportunity to stray from the methodical ritual of embalming or cremation. It’s a decision fitting for a game dedicated to respecting the craft and demonstrating its normalcy.

That isn’t to say that Charlie is completely without agency. When the family of a young suicide victim opts to ignore the will of the deceased (which is perfectly legal, as it wasn’t witnessed or notarized) and have an open casket funeral rather than the requested cremation, Charlie, and by extension the player, are given the opportunity to opt out of participating. It’s made clear that the funeral will go ahead regardless – Rose & Daughters are unable to respect the wishes of the dead over those of the family. So instead of being a plot-altering, “your choices matter!” style opportunity, the decision becomes a thought provoking exploration of post-death autonomy, (and a cleverly implemented content warning and avoidance system).

Compounded tragedies

Even these small freedoms fall away when Rose & Daughters is acquired by the Hillside Heritage. The new owners lecture Charlie in the importance of upselling grieving families, particularly overruling families who want cheaper and more personal at-home ceremonies. They outright ban green burials (which are eco and budget friendly). Charlie’s coworker, the hearse driver Matthew, quits quickly.

Charlie is signed up to an industry newsletter that explicitly addresses post-death transphobia: “There have been notable situations where trans women have had their wishes overruled by their families, and have had their hair cut, are buried under the wrong names, and subjected to the wrong pronouns in their obituary announcements.” Charlie isn’t asked to do this, but with the other pressures that Hillside Heritage puts on her, and with even Rose & Daughters being forced to overrule the wishes of the aforementioned suicide victim, it’s easy to see how these tragedies can occur.

A Mortician’s Tale cleverly weaves these concerns into a story. It demystifies death by facing it head-on, without shying away from the problems that the industry faces. It simultaneously cuts through taboo and showcases the troubles without compromising either aspect.

Charlie’s story ends with the burial of an infant. It’s a happy ending. In the complex world of A Mortician’s Tale – so, our world – those two sentences aren’t contradictory.