History and video games are like peanut butter and chocolate. They fit together perfectly, and until the day comes when David Hayter clones himself, there shall be no better pairing. It’s such a shame that there aren’t more history-focused games out there. It’s a bigger shame that the majority of the ones that do exist focus exclusively on war. War makes a morbidly fascinating subject matter for a video game, but there’s so much more to history that game developers and publishers ignore.

Like for example, 1920’s San Francisco. That’s exactly the setting developer Ben Wander chose for his game, A Case of Distrust, an E3 favorite that came out of nowhere like a rush of hot air. Wander even found a way to make this combination better: he made it a mystery game as well.

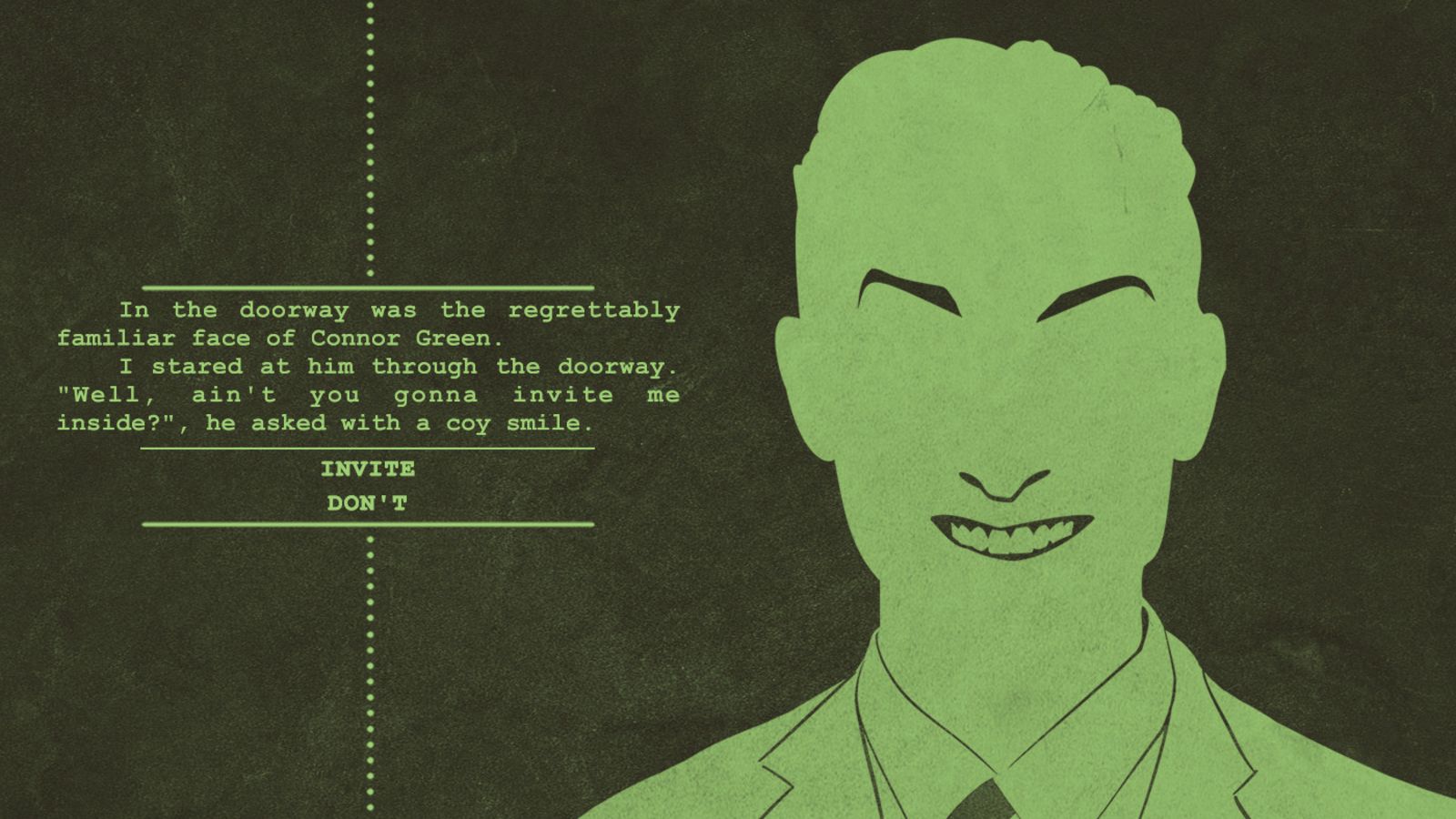

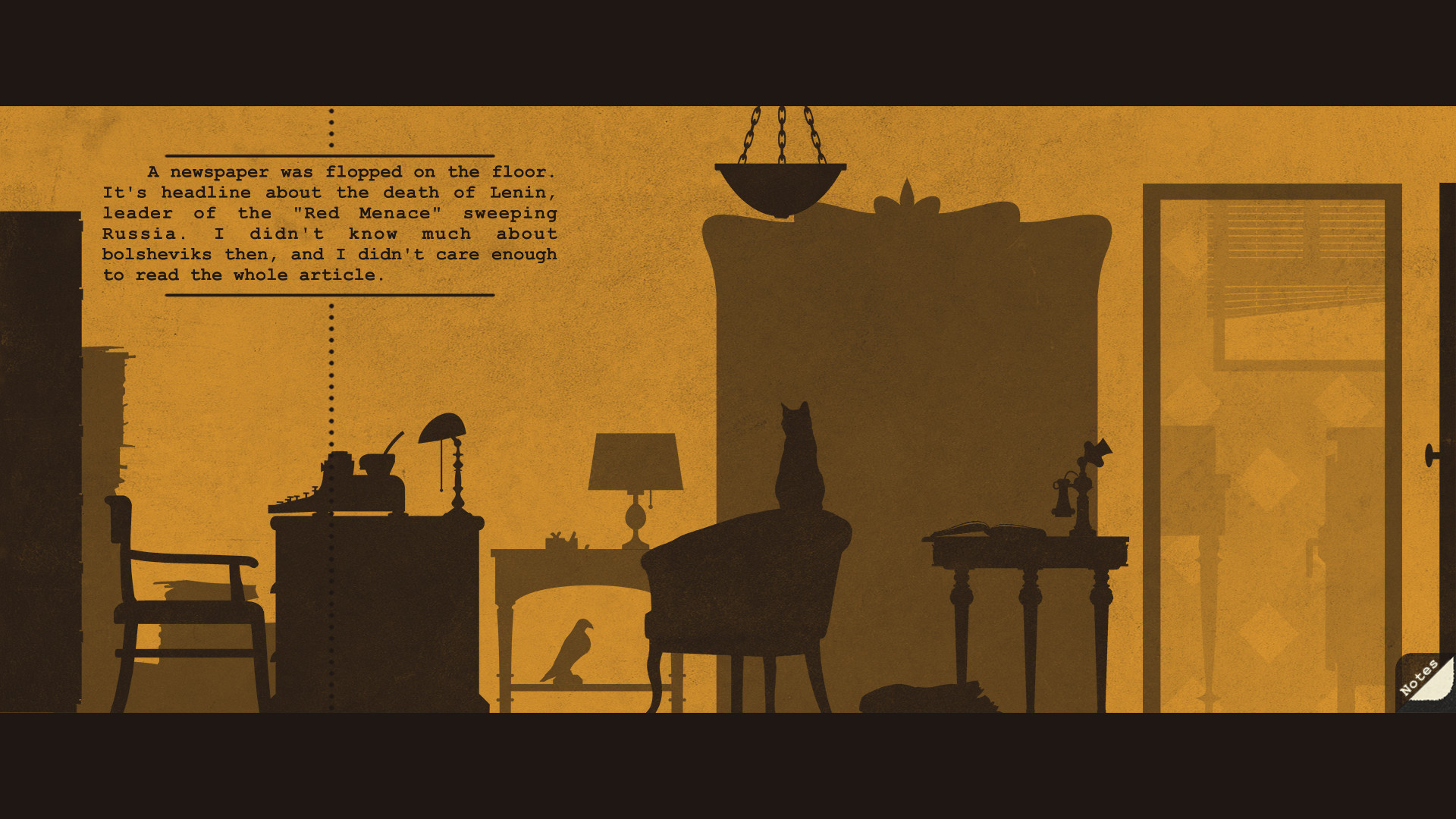

In A Case of Distrust, you play Phyllis Cadence Malone, a female private investigator in 1924 San Francisco. “This is the game Ben Wander left AAA development to make, founding The Wandering Ben in 2015,” the game’s press page reads. It’s no wonder he had to go indie for it. As well as the unique subject matter, the game also plays differently from any AAA game. It’s a text adventure, closer to 80 Days than Zork, and features minimalistic graphics that sells the hard-boiled, noir setting, one that promises to put a different spin on the well-worn genre.

To get a better understanding of the world of A Case of Distrust, we sat down with lead developer Ben Wander to talk about his game.

Cliqist: A Case of Distrust is everything I’m about, history and mystery. I’m curious what made you decide to blend the two together in an adventure game.

Ben Wander: I’m thrilled to hear you say that — I love history and mystery too!

I wish there were more historical games! There are vast amounts of untapped inspiration from our past — worlds that we haven’t explored, themes that tie to contemporary ideas. And, maybe, players can learn about the period while having fun!

I wish there were more mystery games! Detectives, especially the novelized ones, lead riveting lives, exploring all facets of humanity at all levels of society. They are clear heroes in their tales, with a definite goal and a main antagonist. But unlike their warring counterparts, these characters must use their wits to overcome obstacles. Why don’t games do more of that?!

A Case of Distrust is a game that I would want to play. Honestly, whenever I step away for a few days then come back to it, I’m astonished how much fun I’m having!

Cliqist: Would you characterize A Case of Distrust as a noir thriller, given the 1924 mystery setting?

Wander: I hesitate to use the word “thriller” for its present meaning. This isn’t a horror game, and while there are a few tense moments, it’s not action-heavy either.

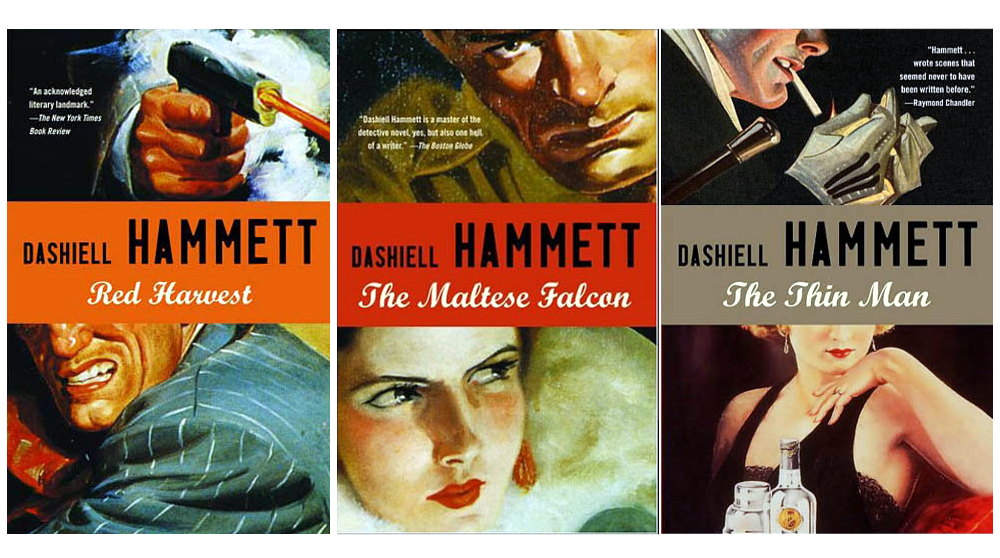

I tried to write it like a Dashiell Hammett or Raymond Chandler novel — hardboiled pulp from the jazz era. There’s a mystery afoot, with layers peeled back as the detective progresses. This game unravels by using your wits.

Cliqist: When you get mystery games like this staring a detective, you usually think of a man, sitting in an office narrating how miserably his life is, but that doesn’t seem to be the case here. Instead, your game stars a female detective. Was that a conscious decision to try and flip the genre on its head and play with the players expectations, and the genre itself, or is that just how the story developed in your mind?

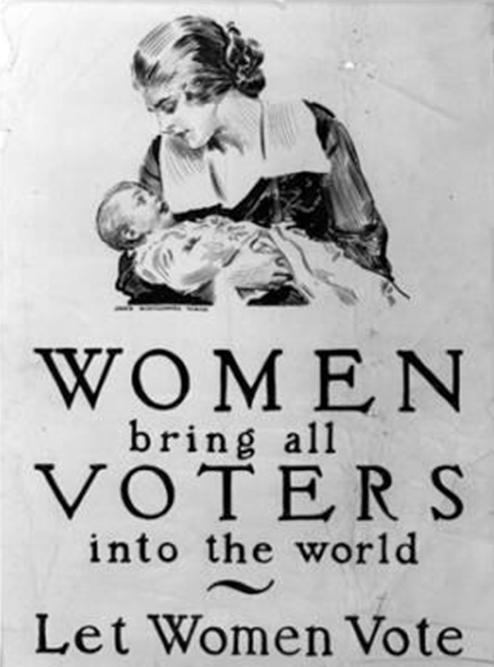

The biggest influence for Phyllis instead of Philip was a mix of 1920s research and our own struggles with women’s equality.

Women gained the vote in 1920. Women started smoking. They began wearing their hair short, their clothes baggy with little flair. They worked alongside men — women miners, welders, woodworkers, mechanics. Emancipation had finally come through. The modern woman was completely equal to man!

Except, not really. Certainly women had the same legal rights as men. But society still treated the sexes differently — after all, this is 30 years before the prototypical American housewife of the 1950s.

As a 1920s writer [Walter Lionel George] put it:

“Though I agree that the American woman has made herself a good position, when I go through a business reference book I find that not one in a hundred of the leading names is the name of a woman. In America man still rules.”

The 19th Amendment, which forbade states from denying American citizens the right to vote based on sex, was ratified on August 18, 1920.

Those themes, unfortunately, still resonate today. While re-reading mystery novels, I couldn’t help but wonder, how would the lives of hardboiled detectives change if they were women? Policewomen existed in the 1920s, but were not equal to male officers, used mostly to comfort victims of “the fairer sex”. And a woman detective was unheard of.

But what if she was a fantastic sleuth? Would anyone notice? Would anyone give her a second look? What struggles would she encounter simply because of her gender?

That nugget of an idea spawned the entire story. Which does tilt the genre in an interesting way, I think!

Cliqist: 1924 was a big year in the United States. It was an election year for the US that actually involved the KKK, it was a time of racism and sexism, as well as prohibition and the roaring 20’s. How much do these external factors of the year come into play in the game?

Wander: There are some large themes to the story — emancipation and prohibition being the most obvious two. But I’m obsessed with the 1920s, having researched so many of its aspects thoroughly. Youthful rebellion (jazz, “petting” parties), disruptive technology (radio, automobile), racism, gang violence, corruption, inequality — the source material is fascinating!

I can’t give proper time to all the aspects, but they’re each so engrossing that I had to find a way to include them. So I created conversations with taxicab drivers — sort of micro-stories in between locations. Players can choose to chat with drivers or not, but each one has a unique perspective on an important issue. I’m hoping players can gain many perspectives from those conversations, in ways that don’t burden my main plot with more themes than it can handle.

Cliqist: I totally agree with you that there aren’t enough history games, and a majority of them always end up being about wars as well. Why do you think the games industry tends to shy away from history, unless it can serve the basis for a shooter?

Wander: Haha, wow, that’s a big question! It’s multi-faceted, and something I’ve thought about a lot.

Many games, not just historical games, center around combat. Starting with a template, like an FPS, defines certain game design elements that developers know will hook, and publishers know can sell. There are challenges beyond the basic design, including how to differentiate the game from competitors, but the fundamental gameplay is fun, and there’s something to be said about starting with a known genre.

But I left AAA to push games in more directions. Don’t misunderstand: I love Battlefield as much as the next player, but combat games shouldn’t preclude other genres, just as action films don’t make comedies disappear.

Of course, I’m not the only one to think this way. Indie games for years, from Flower to Gone Home to Her Story, have been focusing on other interactive aspects.

Of course, I’m not the only one to think this way. Indie games for years, from Flower to Gone Home to Her Story, have been focusing on other interactive aspects.

So why don’t more indie games include history? I don’t know. They’re rich worlds already created. They share themes with contemporary ideas. Players can use the work as a springboard to further curiosity. I love historical fiction for all these reasons, which is why I’m doing it myself!

If I were to speculate, I imagine it’s because historical accuracy is challenging. Create your own fantasy world, or start with a world you know intimately, and players accept your rendition of it. But get a piece of history wrong — or maybe worse, represent history in a disagreeable manner — and suddenly the entire internet knows your folly.

I just happen to love the 1920s, so I’d already extensively researched the period before even thinking about this game. But that doesn’t mean I can’t be wrong, and that terrifies me with the internet! I’m nervously laughing at my keyboard now.

That said, the fact that fewer games are set in historical times might be a good differentiator. I know I want to play a game set in our real past, and it sounds like you do too. We can’t be the only ones. So let me make the gamble! I’m betting that there’s more of us gamers out there — and maybe some non-gamers that I can attract as well!

Cliqist: You mentioned the struggles a woman detective might have had in the 20’s. I’m wondering, how do those struggles manifest in the game? Will that be a plot thing, or would it also affect the gameplay somehow?

Wander: Malone is a great detective. But most of her contemporaries don’t believe her, and she has to work much harder to earn the same respect naturally given to a white, male detective of the same period.

That manifests itself in her own self-doubt, too. A heightened imposter syndrome, which I also feel at times.

I suppose it’s intrinsically part of the gameplay just like it’s intrinsically a part of her society (and, in a lot of ways, ours as well). It’s not as if there’s a UI button the player can’t interact with because they’re playing a woman. But there are assumptions she has to overcome.

Cliqist: I love the idea of talking with taxi drivers to get a little more context about life during that time. It kind of reminds me of 80 Days, where you could talk to people in each city you traveled to, and every city had its own, self-contained story, but you could also get useful information about travel routes too. Will these conversations with taxi drivers possibly give you clues as to the case you’re working on, or will they be completely independent of the plot?

Wander: An 80 Days comparison! I love that game and play it constantly for reference! I’d say, similar to their in-city exploration, the taxi conversations are mostly flavour. In fact, they’re completely skippable, and entirely randomized — so you might not even see all of them in one playthrough.

Those conversations are to get to know more of the world and the themes that aren’t inherently part of the story. But the travel mechanic itself is used to get around the city — and if a player just wants to get on with the mystery, I don’t want to punish her because she doesn’t care about President Coolidge’s views on immigration.

But, as a lover of history, I would want to know that. So it’s an area players can freely explore at their leisure.

Cliqist: I realize I was so wrapped up in the setting that I didn’t ask much about the plot or gameplay. So, will there be one overreaching mystery you have to solve throughout the game, or will there instead be a series of mysteries that need solving?

Wander: Like any good hardboiled mystery, the case isn’t exactly what it seems at first. So you will have to solve multiple facets, but it all ties back into an overarching mystery.

Cliqist: How would you describe Phyllis? Does she see herself as some kind of force for change for women, or is she simply just trying to do her job as a detective?

Wander: I tried to write Malone with some internal conflict on that. I didn’t put this part of her backstory explicitly in the game — though maybe I should! — but as a wide-eyed teen, she had a random encounter with Alice Stebbins Wells, the first American policewoman, who was a big force in the emancipation movement. That’s what started Malone on her dreams of become an investigator — to change society for the better, to prove that women are equals when given the opportunity, to break barriers for future generations.

But some days she wakes up in her tiny apartment, with only thankless adultery cases, trying desperately to just continue as a PI — or maybe thinking of giving it up for a more traditional lifestyle.

It’s in some ways an exaggeration of my own internal dilemma. Can I push games in new directions? Or am I just trying to survive as an indie dev? Should I just take contract work or go back to AAA?

I think those themes resonate with many people in different walks of life. Everyone has internal doubts, even those who don’t share them publicly. Though Malone dreams of becoming that force for change, she’s afraid she might not be able to be that person.

The Ku Klux Klan, once relegated to the history books, was reborn in the 1920’s, seeing a rise in popularity and new membership.

What a fantastic conversation. It’s not often you see developers willing to be so open about their game and their ideas, and it’s always a joy when they do. It’s even less often a developer quotes a magazine from 1921, and provides a citation for it. A Case of Distrust is scheduled for release sometime later in 2017. You can bet we’ll be keeping a close eye on it.