If you’re into horror, you’ve likely heard the term “pacing” before. A lot of people—critics, especially, because we’re smarmy pricks with English degrees—bring it up whenever they write about horror games. A lot of us are quick to point out that many horror games fall short because of poor pacing.

But the word gets thrown around a lot by people that don’t fully understand what it is. Why is it so important in making a certified Spooky Game™ (or, really, any good story in general)? That’s a good question! Hopefully I can answer it for you. Not that I’m qualified or anything. You’ll just have to take my word for it.

What is Pacing?

So first of all, what the hell is pacing? To put it simply, pacing describes the tempo of a scene in a story. Most stories have two speeds: fast and slow. Fast scenes are your action sequences, your chase scenes, your monster battles, whatever. They’re the scenes in Marvel movies where Iron Man is punching a guy while Spider-Man makes fun quips. Slow scenes are usually dialogue scenes; moments of downtime where the characters interact or details of the plot unfold. Whenever you see out-of-costume superheroes around a table discussing whether or not the bad guy is bad, that’s a slow scene.

The very first rule of Screenwriting 101 is that you should never overlap these scenes. Imagine watching a Marvel movie, and right as Thor brings his hammer down on Thanos, they cutaway to Gamora explaining how the Infinity Guantlet works, and then we cut back to Thor landing the hit. It’s jarring, right? Tonal whiplash. Your brain doesn’t want to learn new information while the action is happening. It’s working hard enough just to keep up. One at a time please, thank you.

The very second rule is that you can’t spend too much time with one over the other. Action pulls you in and puts you on the edge of your seat, but nonstop action can be tiring to follow, and without the slower scenes there’s no meaning or investment in what’s happening. Slow scenes—with no rising tension or conflict at all—get boring if they drag on for too long, because we’re here to see some drama unfold.

This chart from Gamasutra’s far more in-depth analysis of pacing provides an example of pacing through Star Wars: A New Hope.

As such, good pacing follows a rhythm (see the chart above). Have you ever described a movie as an emotional roller coaster? That’s good pacing. The fast scenes are interwoven with the slow ones. You’ve got heart racing action (the drop) and slower, more cerebral moments to take a breather (the rise). Generally speaking, a good story will save its largest drop for last, with smaller humps building up to it.

How Does This Apply to Horror?

In horror, pacing is a bit strange. The slower scenes can go on for a bit longer, because the audience knows they’re here to get scared, and they know they scare most easily when their guard is down. Even in really slow moments, there can be enough tension to keep you from relaxing. That said, the same basic rules apply: when you have a drop (a jump scare, a chase sequence, a monster introduction, whatever) you have to come back up. You have to rise before you can fall again.

And in horror, that rise is more important than the fall. Imagine yourself on a roller coaster. What do you freak out about: the drop, or the slow and steady climb to the ride’s highest point? Yes, the drop is scary—and it’s why you’re there—but the drop would be far less satisfying without that slow, dreadful climb. There’s a reason they make the chain clank so loudly as it pulls you up.

Every successful (or at least renowned) horror game follows this rule. It terrifies you with a chase sequence, or a monster introduction, or a boss fight. Then, it slows things down and lets you explore. Usually, this is when the game starts dropping plot beats on you. Your brain will desperately want to calm down, so it will be at its most receptive state here. After a tense moment, finding a file can be like a godsend. Normally you wouldn’t care about Jack McKeepsAJournal but anything to distract from the tension is welcome.

When you’re constantly scared, you get exhausted. You shut the game off, or your brain stops reacting to what’s happening, because you expect scares around every corner. But when you have moments of calm and quiet, your “pants-shitting” meter refreshes a bit. It allows the game to more effectively get under your skin.

Incidentally, this is also why horror games tend to have puzzles. By making you wrap your head around a logic puzzle, the game is forcing you to let your guard down for the next tension-rising moment. Sneaky, sneaky!

Effective Pacing in Horror Games: A Steady Rise and Fall

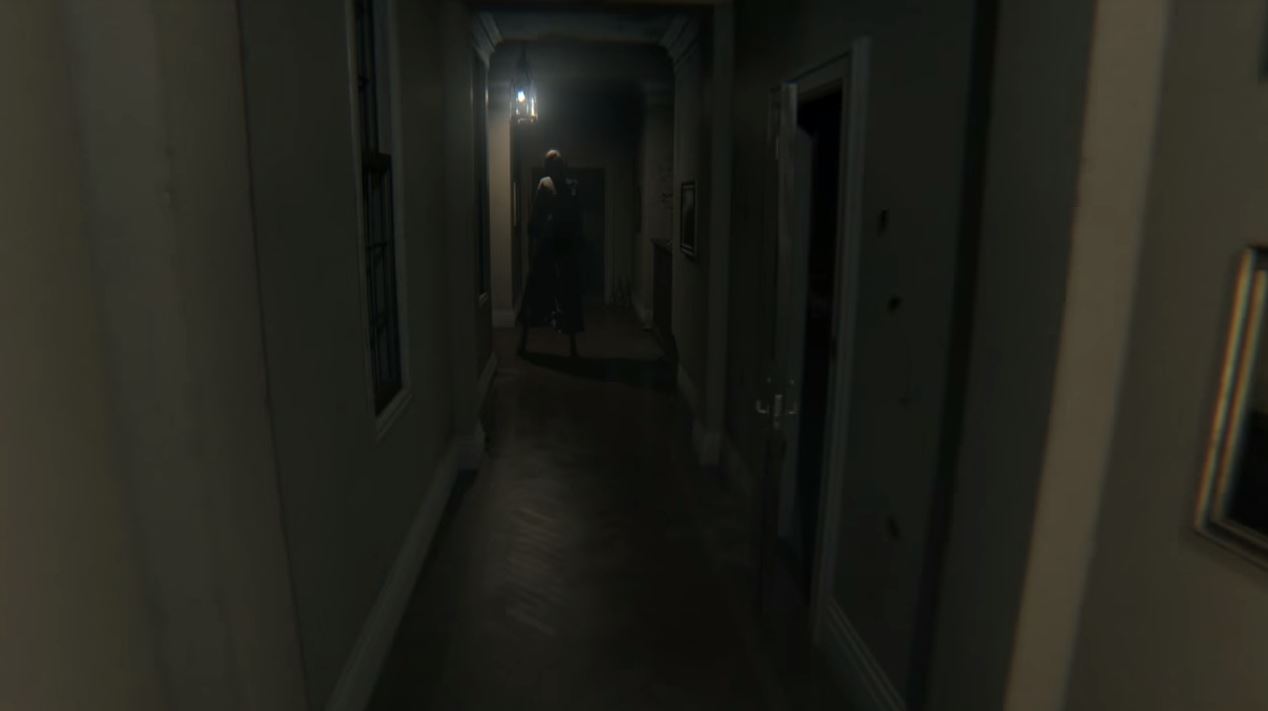

Remember Amnesia: The Dark Descent? Think about all of the horror games that came out shortly after it launched. Outlast, Among the Sleep, Neverending Nightmares, and way too many indie games to count; suddenly, defenseless horror games that placed emphasis on stealth were all the rage. But what sets Amnesia apart from these games, even the ones that alter and improve upon its formula?

There are multiple factors, but out of most of those games, Amnesia has the best pacing. Amnesia’s most terrifying, crucial moments ALL follow up with some breathing room.

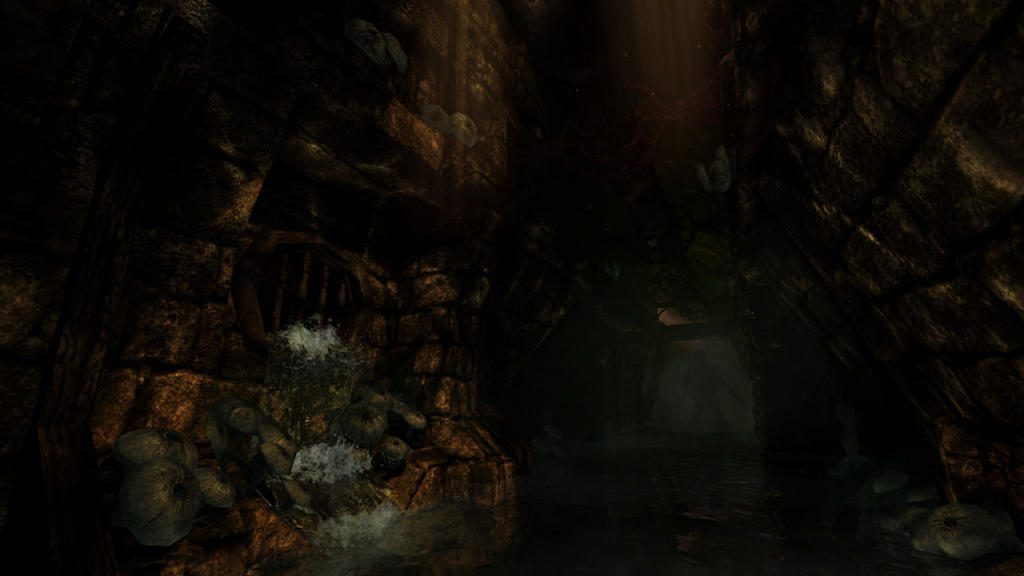

Think about the dreaded “water part”, for example. You’re stuck in a partly flooded cavern with an invisible monster that chases after you whenever you enter the water. In every room, there is a convenient box or two to climb on to stay safe. But as you go further through the area, the boxes become fewer and farther between, forcing you to spend more time in the water. Eventually there’s a timed puzzle where you have to lure the monster to one side of the room, jump in the water, and then slowly twist a valve to open up an escape route. It’s tense, to say the least.

The final moment is a chase sequence with no safe spots. You can only run, culminating in the final stretch where smaller boxes and bits of trash block your path, and you have to frantically throw them about to escape. Immediately after that, you escape through a door and enter a well-lit area, complete with a soothing melody. The game is patting you on the back. You survived, you can take a moment to chill.

A whole ton of indie horror games nowadays are basically just chase simulators. They looked at Amnesia and thought that the defenseless, frantic chases were the key to making a good, memorable horror game, so they pepper their games with them generously. But without the rising action—that careful, patient climb to the top of the roller coaster—those chases are far more annoying than scary, no matter how many lazy jump scares they throw at you (lookin’ at you, Outlast).

A lot of games (Amnesia included) will sometimes take a safe spot and turn it against you, but this should be done sparingly. Remember: horror is most effective when it catches you off guard. And the only way to lower someone’s guard is to make them feel safe. Trick them too often, and their guard stays up. In short: you NEED real, 100% safe downtime.

Let’s Talk About Silent Hill – An In-Depth Example of Pacing

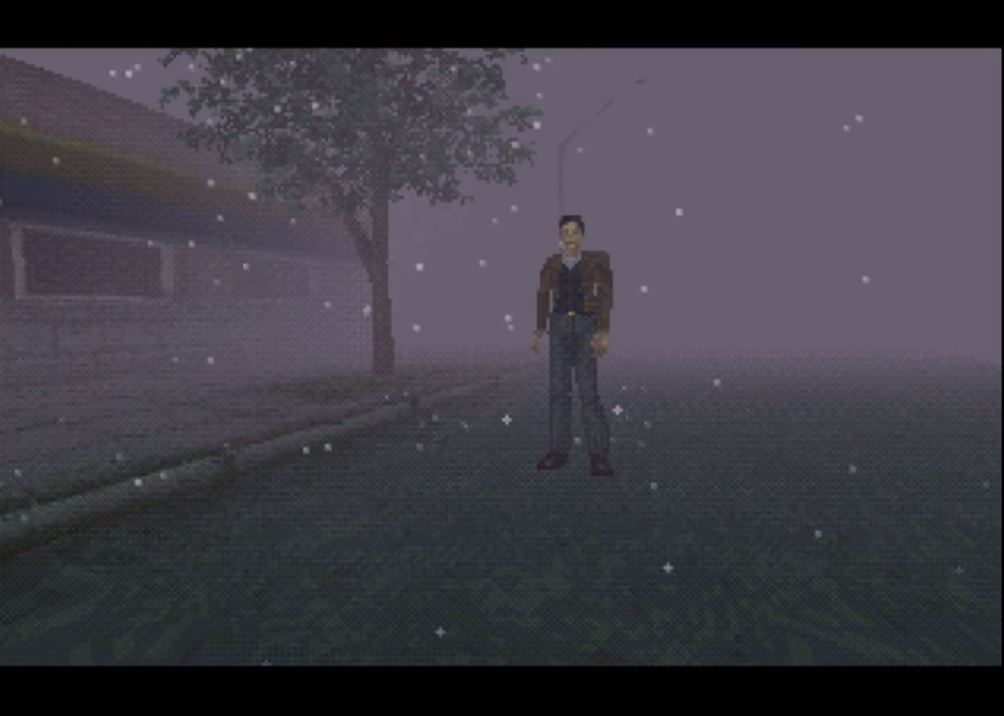

So let’s look at an another game that inspires and influences countless titles: Silent Hill. Specifically, we’re going all the way back to OG, PS1 Silent Hill. You know, when gripping terror looked like this:

There are some important things to remember before I dive into this, especially if you didn’t play Silent Hill close to its release: a lot of what I’m about to tell you has been copied to death. Silent Hill, by today’s standards, has no unique tricks. Nothing that really surprises you. But back then? HOOBOY, a lot of this shit was unprecedented.

When you boot up Silent Hill, you’re treated to an intro that briefly recounts the events leading up to the beginning of the game. Harry Mason is taking his daughter Cheryl to Silent Hill, a quiet little tourist town in America. To cut a long story short, some weird stuff goes down, and Harry crashes his car trying to avoid a young girl in the road. The game begins with Harry waking up in his car to find his daughter is missing, so he sets out to find her.

Already, things are a bit off. It’s snowing in the middle of summer. There’s a thick fog blanketing the whole town, limiting your vision and the PS1’s draw distance. The town seems deserted; there isn’t a single person in sight. Harry briefly comments on it before his attention snaps back to finding his daughter, and he spots her in the distance. She runs off, prompting the player to chase, and turns down an alleyway that would permanently etch its way into the memories of every single person who played this game when it launched.

As soon as you enter the alleyway, you see the bloody remains of an inside-out dog splattered on the ground. It makes nasty little crunching noises if you step on it (which you do, because tank controls take some getting used to). This is the first major part of the rising action: here, we now see present danger. Something has obliterated a dog, and it could be close by. More pressingly, Cheryl might be in danger. Shit!

As you make your way down the alley, it twists and turns constantly. The camera flips around a lot to disorient you. After some time, an itch forms in the back of your mind: isn’t this alley a bit too long?

When you enter the next door, the sun goes out completely. It’s pitch black. The snow turns to rain, a siren is heard, and the ambient spooky background noise slowly morphs into something more sinister. Harry gets out a lighter—the best he has on him—and you trudge on.

You hear the sound of creaking metal in the distance. Proceeding with unnerved caution, eventually you spot the source of the noise: an overturned wheelchair, seemingly abandoned. Not dangerous, but strange.

After another few turns, you encounter a dead body on a hospital gurney, wrapped up and primed for the morgue. Again, this is strange—and arguably a bit spookier than a rusty wheelchair—but not dangerous. None of what you’re seeing makes sense. You’ve gone from a normal alleyway to a labyrinthine corridor filled with random hospital equipment.

At this point, you’ll probably notice how the floor and walls have subtly changed. The brick walls now look metallic, and there’s rust everywhere. Parts of the concrete have melted away to reveal grating. Behind them is an endless void. It’s as if you’ve entered another world.

Soon, you start to see blood splattered on the walls, and a trail of it leading through a thin corridor. The music hits its peak, and then a cutscene plays out. Harry spots a bloody, mangled corpse, strung up and crucified on the wall before him. Harry, because this is a poorly acted game from the 90s, gives an exasperated, “What is this?” before you resume control.

Now, you’re surrounded by small humanoids (children?) with knives, and they’re swarming you. They grab at your legs and dig their knives into them. You’ve got no weapons, so the only thing you can try to do is run. But even if you make it back where you came, you’ll find a fence has appeared and blocked you in. Try as you might to survive, Harry eventually slumps over…

…And wakes up in a nearby diner. Was it all a dream? The tension shatters when it hits its breaking point (as a player, you probably didn’t know you were being tricked) and you’re left with brief confusion before a police officer steps into view and a cutscene plays. You get some exposition, a proper weapon, and are now free to explore the town freely in your search for Cheryl.

Compare that to how Silent Hill 3 opens. In that game, the main character Heather starts in the nightmare world. You’re armed to the teeth and find yourself fighting through a menagerie of crazy looking monsters. Eventually, the monsters will kill you (or you’ll reach a scripted death sequence at the end), and Heather wakes up in a nearby diner to find a weird police officer has been stalking her. That’s some consistency, at least.

These moments follow similar beats, but it’s rare you see people talk about Silent Hill 3’s opening. There are of course several factors to this (the third game, in general, isn’t as nostalgic or groundbreaking as the original for most fans) but I would argue that the original game’s opening is more memorable because it understood how to show you its hand one card at a time. Team Silent knew that the crazy nightmare world and knife-wielding monsters weren’t enough; they needed to build up the scene perfectly, so that the reveal would resonate harder. Not to mention how long the corridors are before the true danger hits, making escape seem impossible.

When describing the scene above, Silent Hill fans often recall the sense of dread and despair they felt as they slowly moved through the winding corridors of a normal alleyway turned living nightmare. The children killing you at the end is just the icing on the cake.

Conclusion

Think about how this applies to horror games in general. When a game marks Silent Hill as its inspiration, what do you get? Usually, you get weird, sprawling level design—probably with a “nightmare” world of some kind—and a large bloke that stole Cloud Strife’s sword, or other over-the-top psychological monsters. You also usually get a story about a dead family member the main character doesn’t remember killing, but that’s another article.

All of these can be good, but these games often neglect the basics. Silent Hill was influential because it found a way to tell a creepy story on limited hardware using a ton of clever tricks and some awesome monster and world design. But it rests on a foundation, and a large part of that foundation is proper pacing. The scary monsters and the themes of entering a terrifying version of the real world were just the seasoning; they’re overwhelming without a full-course meal to adorn.

Silent Hill placed all of its emphasis on the build-up, and saved the fall for when it knew it’d get you the hardest. If you crank the tension up to 11 and keep it there, eventually your players are going to get worn out and either turn the game off or numb themselves to the scares. Then the worst thing possible happens: they’re going to find your game boring, or at least too edgy.

Pacing is a simple tool, but it’s essential in keeping your audience engaged and open to being terrified. Remember: the more you let your guard down, the more effective a scare will be.

…

…

Hey Google, how do you write a jump scare into an article?