My grandfather passed away at the age of 97 years just the other day. He had been struggling with sickness and decay for quite some time, and his expiration date was always growing closer in sight. A handful of days preceding, lead vocalist of The World is a Beautiful Place & I Am No Longer Afraid to Die, Tom Diaz died due to as of yet unreported instances.

There is an irony to these deaths, besides the title of Diaz’s musical group, or the fact that my mother called me a day before her father’s passing to lament over his moving into hospice. I was playing Return of the Obra Dinn upon hearing about both of these instances, staring down Death both inside and outside of accepted reality, thus bridging the two and erasing the confines of media escapism. The game’s deaths became real; nonfictional accounts of people struggling to survive and failing terribly.

For Obra Dinn, Lucas Pope‘s latest masterwork, does not merely portray a snapshot of the very act of death itself, but aims to recall humanity’s mortal failings. People die because they were once people, living persons entrenched within the confines of a material world clawing and clutching at their souls. Once again, the auteur turns an otherwise menial task of identifying and rule-following into an emotionally-wrought venture which feeds on the conflicting compassion of its audience.

The Game’s Deaths Became Real

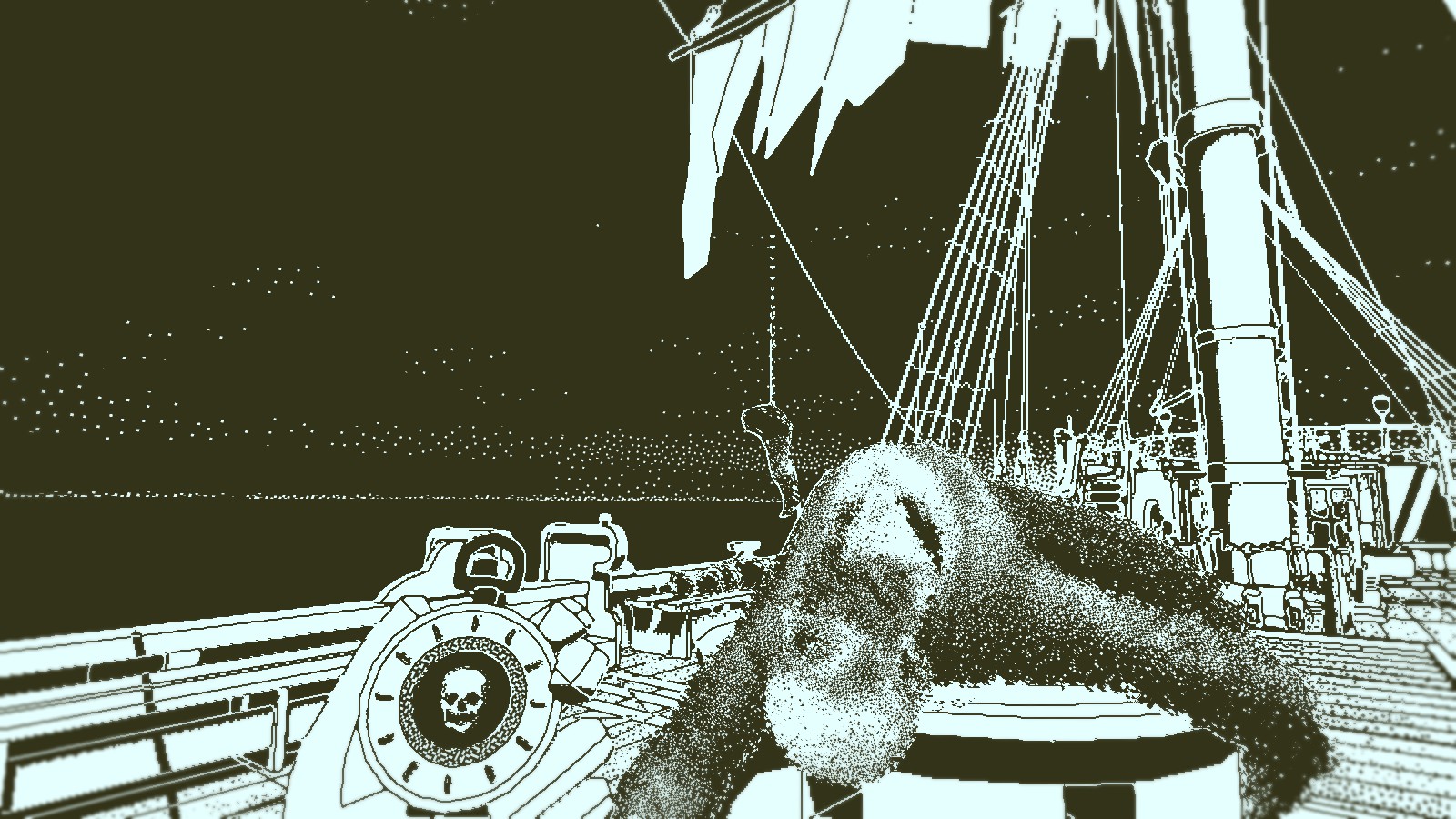

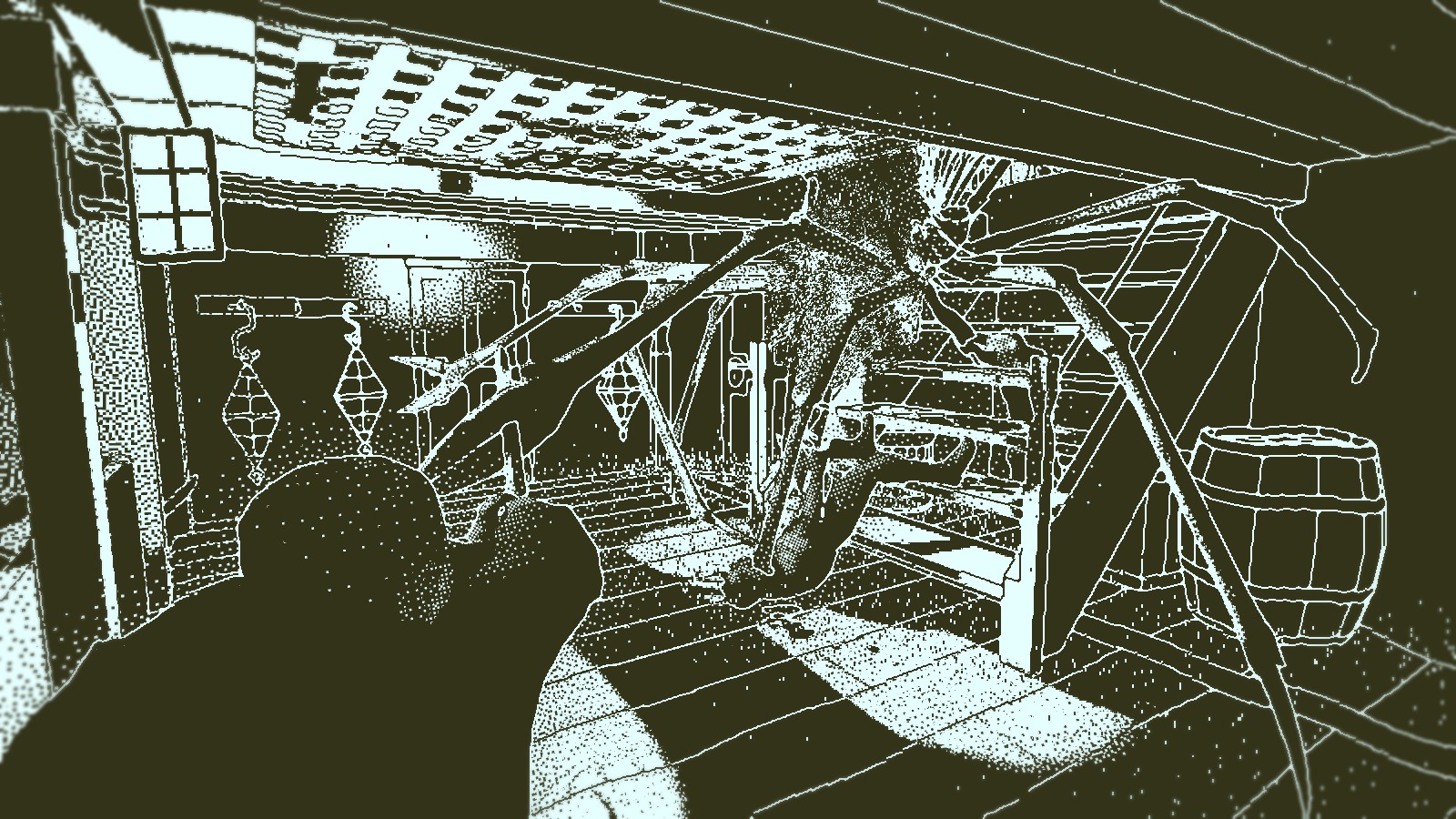

This sea-faring title, a nautical story told through an extended sequence of demise, intermittently devised by the player’s own catalogue of each shipmate’s demise; is submerged in chaos. It is a game devised by a litany of details both serving as illustrative characterizations, as well as a means of edging the player on to their next “A-ha!” moment. For Obra Dinn is a methodical puzzle game, evinced by tragedy, one in which its audience is met face to face with the very notion of mortality, time and time again.

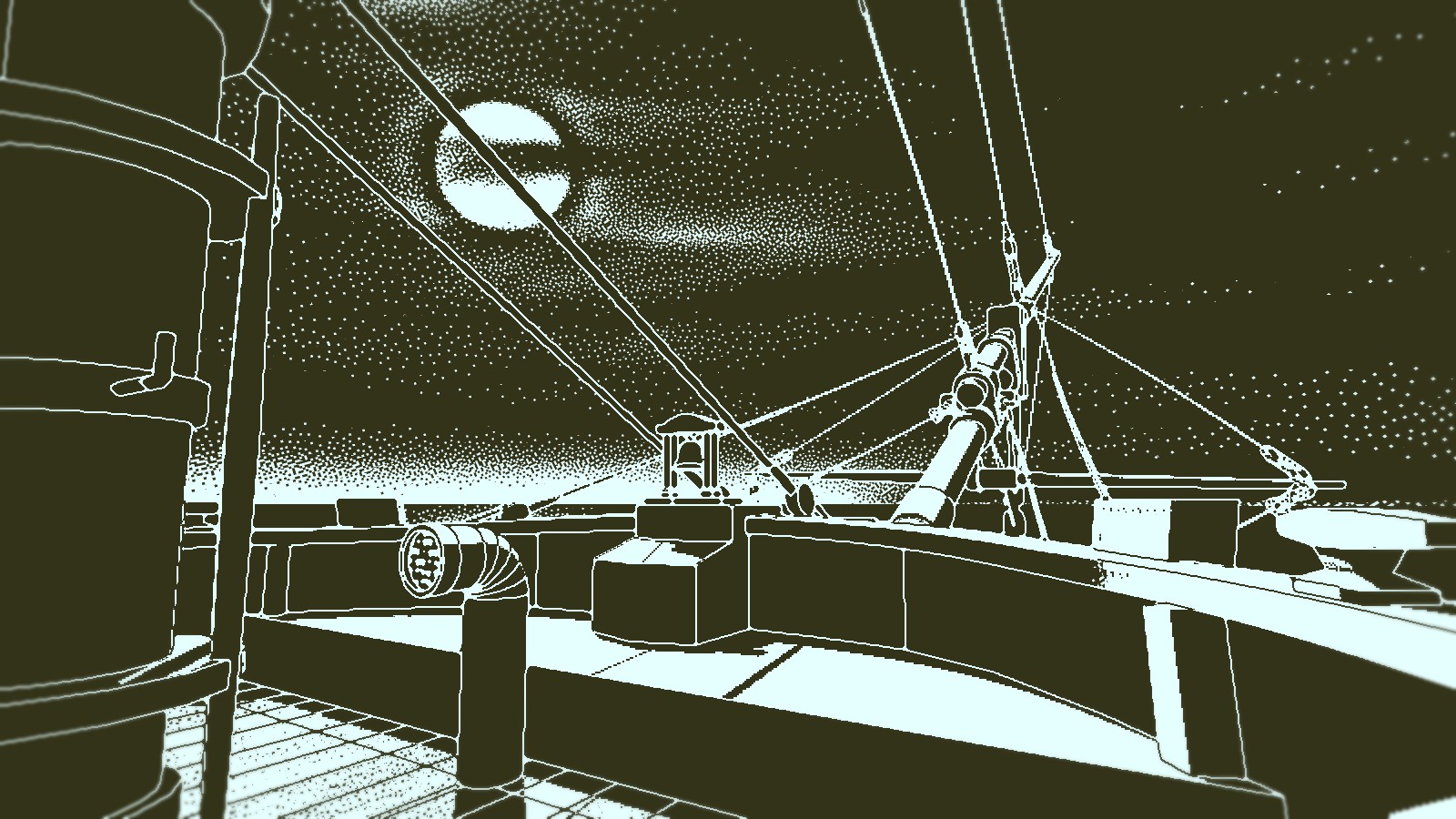

The game does not so much present a cinematic experience, but suggests one, pausing the drama mid-sequence during flashbacks of dire circumstances, to allow the player to freely explore the very orchestration of a moment. How does one draw a beating heart? With lines of expression, of course. And so the game refuses to show us the action of any given scenario, only allowing us a glimpse through auditory recollection.

That is, up until the fatal blow lands on whatever slain shipmate has been discovered, during which time itself halts, solidifying the moment for an eternity. The player is then tasked with deducing the cause of death, over and over throughout the game’s runtime, reliving the very last instance of Life for these dozens of tragic figures lost at sea.

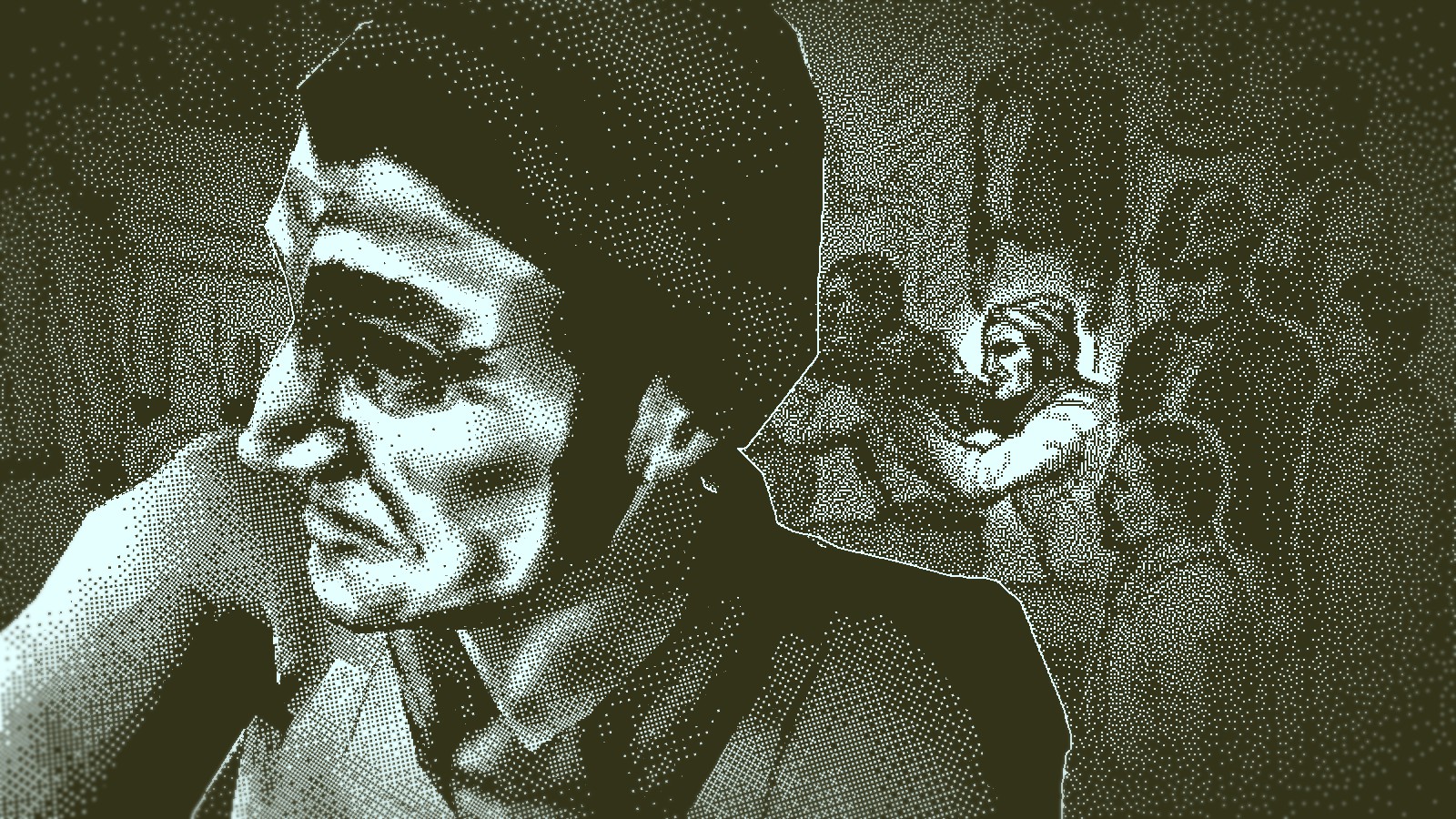

In RotOD, an artist’s sketch opens up to the three-dimensional realm for an audience to become connected to the past through historical documentation. A sketch of the crew members becomes a gradually-unfolding record of living persons, the visual details slowly materializing as the investigator learns more about them. Lucas Pope, the one-man team behind this title, studiously weaves a large-scale tragedy aboard the eponymous craft, and then tasks the player with linking faces to their fates.

A Reminder of Mortality

However, similarly to his remarkable 2013 title, Papers, Please, the cast of sixty voyagers are implicated through very limited means of illustration. Like a portrait of decay, each harrowing sequence aboard the titular vessel suggests these individuals as strikingly unique personas through Pope’s deliberate hand in deviating each from one another.

Miraculously, this technical character design both aids in the player’s deliberations, as well as brings a bona fide aura of humanity to the entire tale, amidst the chaotic mystical beings and cursed objects ushering the tragedy of it all. The game’s greatest achievement lies in Pope’s ability to expand upon his character’s personalities by using the player themselves. Critical thinking is required to reach Obra Dinn’s conclusion, and as a result, the player grows closer and closer to the victims they are studying.

The game functions as a sort of psychological manifesto, a grand murder mystery in which the the identities of the victims themselves serve as the primary subjects of concern. Pope carefully crafts an often-supernatural voyage that is deliberately set in the past, utilizing the function of time travel as a means of bridging tragic history with the present, allowing the player to sympathize with those who have met their doom.

Whereas Papers, Please garners sympathy for its cast of randomly-generated characters by obfuscating their fates at the hand of an oppressive regime; each level of Obra Dinn locks the player’s viewpoint on the death itself, monotonously flashing a brutal reminder of mortality on screen to elicit shock and awe.

Tragedy Plus Time

By participating in the investigation of the Obra Dinn, the player legitimizes the lives of its victims, resurrecting their souls to deny any form of corporate digitizing. The job may monetize their lives for the sake of erasing history, but by actively investigating each voyager, they live on through memory and legacy. Pope’s masterwork fundamentally utilizes the player’s head space as a means of validating humanity, recalling their own essence of mortality at each and every branching curve.

It can be easy to neglect the savagery and demise underlying the course of human history. Tragedy over time becomes ignorable, as human connection to past events grows separated by a rift in cultural understanding. Pope understands that humanity, as a concept, remains intact in spite of the years, that the impact of every era is deemed implicit in the modern age of civilizations.

By so wondrously linking the present with the past in his stupefyingly complicated array of tragic memories and eradicated personas, Pope reestablishes the human center of tragedy, utilizing detective game functionality and player agency to elicit compassionate reaction to his cast of motionless voyagers. Return of the Obra Dinn does not so much redefine the adventure game genre, but fulfills its effective potential. A sketchbook of horror and death becomes a playground for sentimental understanding.