“Everyone is invited, to write something about how to make a videogame, how to respond to a videogame, what the field of videogames could and should be. Write a manifesto to free up your mind to move forward. I want videogames created with vision rather than received wisdom that both fail and succeed at meeting that vision. I want uncompromising, unconventional writing to respond, recover and reshape.”

This is how Emilie Reed conjured Manifesto Jam into being. 121 entries later, with works ranging from sunny and enthusiastic to charged with iconoclastic drive – from the abstract to the concrete – the jam now represents a diverse spectrum of ideas on how to make, and talk about, games. Emilie was kind enough to speak to Cliqist about the process.

Coming Unstuck

Cliqist: Hi Em! Thanks for speaking to us. Would you mind telling our readers a little bit about yourself, and how you came to be involved in Manifesto Jam.

Emilie Reed: Hi Nic! I primarily consider myself a writer and curator with a background in modern and contemporary art history, and I’m currently working on research about how videogames are historicized and displayed in museums. Before taking on this research I started out writing for The Arcade Review which put me in the games crit/altgames space. AR was a really ambitious publication in terms of writing about games with the same cultural context and critical rigor you see in really good art writing, and I took that with me even after it shut down.

Manifesto Jam was the second writing jam I’ve organized, partially in the spirit of encouraging experimental, ambitious approaches to writing the same way game jams should promote that in game making. Writers should have fun too, right? So the one last year at around the same time was a visual essay jam. I think an unusual format can also be good to get people unstuck from what they think writing has to be like. I wanted to do something similar again this year, and I was torn between doing another round of visual essays, or manifestos, based on Robert Yang’s blog post where he suggests a #GameManifestoJam. I asked a few friends and they all seemed more excited about manifestos, which is also a kind of experimental and unusual form, so I went with that!

Writer John Berger, the inspiration for Visual Essay Jam

Challenging Complacency

Cliqist: I won’t ask you to pick a favourite from so many submissions, but if someone wanted an entry point to Manifesto Jam, are there any pieces you feel summed up the project in the way you anticipated? Similarly, were there any entries that completely surprised you?

One manifesto that kind of took the approach I was expecting, but I still enjoyed a lot was Mitch Alexander’s Monstrous Love and Heroic Failure manifesto. In a very clear way it lays out the issues with a very common game formula, hero fighting monsters, and lists concrete ways to challenge and subvert it. You can definitely see this ethos in his orc dating sim game Tusks , which humanizes “monstrous” creatures and makes them sympathetic and desirable instead.

“Tusks” By Mitch Alexander

I was happy to see people take the time to think about their practice and put it into words because that was an intended outcome of the jam. Some entries that surprised me were like Holly Gramazio’s proposal to destroy all games at the end of the year , every year… this one and a few others proposed something that was kind of inherently impractical or impossible, which is obviously something the manifesto form lets you do but something I didn’t foresee coming up! Holly’s especially sticks with me because when I think of the problem of preserving the history of videogames, and how complacent people can be with the idea that they’ll be around forever or what’s important will survive through emulation, the internet, or your infinite Steam backlog… forcing everyone to participate in a kind of collective memory project instead if they want to know about an “old game” is kind of appealing!

Openness and Flexibility

Do you feel there’s anything unique about itch.io as a platform that makes it a good fit for non-traditional projects like this? Does the medium affect the message at all, to borrow a tired McLuhanism.

Itch.io is a really flexible platform and I have released all kinds of things there. Some games, but also zines, and my writing jam entries, and I’ve also seen people putting their comics, music, software tools and writing on the site.

Emilie Reed’s Midnight in Dundee

There’s still a few spots in the UI where it’ll default to calling your thing a “game” but overall the structure of the site and community seems really friendly to a variety of approaches. I think sites like itch, where there’s a lot of openness and flexibility and everything isn’t decided by user feedback or commercial oversight like on Steam or app stores is so important for an arts community around videogames, and the structure it has for setting up and running jams is super convenient and accessible! So yeah, without itch.io it would have been a lot harder to organize and get a community around an event like this. However, one vestigial element I don’t like is that it seems like you can star rate everything by default! I just think it’s unnecessary. Usually on itch your feedback is going straight to the artist or small team that made the work, and that’s probably the least useful type of feedback. #manifesto

Coexistent Contradiction

In your Medium piece you said that you “wanted to see if we could expand both who felt qualified to make arguments about games, and how thes arguments can be put forth.” A jam acts as a democratization of ideas. At the same time, a manifesto is both fundamentally authoritative, and deeply personal. How do you anticipate the contributors ideas informing each other, moving forward?

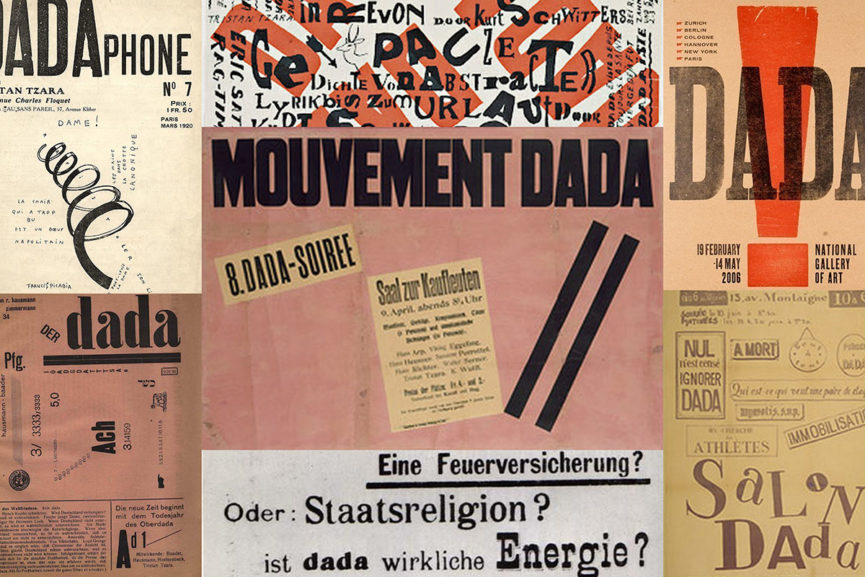

The value of the manifesto form to me, after reading a bunch of manifestos from people who don’t really consider themselves academics or experts or “proper” writers is that it lets you try on the voice of authority. It’s like if everyone got to stand at a podium for a bit during a meeting, or everyone took turns sitting at the head of the table. Academia and the art world are overall varied fields, but a lot of time they attract the same type of people, and reward the same type of approaches.

artfluids’ Directorcore Manifesto

Even in a young and kind of contentious area like game studies, there’s pressure to formulate and evidence your ideas a certain “formal” way. So I don’t think the authoritative voice of the manifesto contradicts with the democratizing aim of the jam necessarily! I think it’s great that they can all contradict each other, and represent different experiences, but also coexist, and I hope all of these ideas being presented together gets people thinking about how there are many ways to approach making or writing about games. And I hope if people make, like, a liàn wù game or a directorcore game, they refer back to the manifesto that inspired them and send it to the writer, so these connections are there and last.

Finding Form

What do you think separates a deliberate manifesto from a more traditional game that wears its design influences overtly? Does a game not represent its own manifesto…uh…manifested, in a sense? Or does a tendency to critique games as products, in relation to a set of ideals, prevent us from taking them on their own terms?

I think all games make arguments about their subject by giving you things you can and can’t do, rewarding certain things and punishing others, but I also don’t think this quality is limited to games! Literature makes an argument about its subject, so does painting and sculpture… even abstract work is basically making an argument about what the form itself should do. The useful thing about manifestos is that they make the fact that they’re presenting an argument explicit.

More Manifestos

There’s a lot of concern about how gamification can subtly manipulate people, (how games that simulate being poor, for example, can actually reinforce negative perceptions of poor people because they present poverty as a problem that can rationally be solved at an individual level) and this is the similar to misogyny and racism being present in visual art and literature because of its structural presence, even if the work is not explicitly “about” those things. It takes study and explication to notice that this is happening, and when a lot of the traits used to evaluate games are based on superficial technical qualities or ambiguously defined things like “fun” or “good gameplay” it’s easy to miss certain things they’re doing. So I would say a manifesto conceals much less than how people typically approach a videogame or work of art.

Finding Momentum

I was in love with your idea that, “All manifestos are Utopian, even ones that seem to be boiling over with disgust and dissatisfaction”. So I have to ask, do you consider yourself an optimist about the future of avant garde creativity in the indie scene?

I am not a big optimist in the sense that I don’t think mainstream or even mainstream adjacent indie studios will make any big moves quickly. But what excites me is that there’s so much momentum and creativity in people who make games as a hobby, or approach it as an arts practice. The landscape is changing all the time and there’s especially a huge variety of idiosyncratic and accessible game making tools online now. But the challenge is this community is largely separate and self-supporting. There’s not much infrastructure to help people make the jump from hobby to arts practice to thing that they can support themselves on. And obviously this has been hurting all forms of art with how public funding and support have been gutted everywhere, but the fact that commercial games are so standardized and themselves multimillion dollar projects made by huge studios makes the gap that much more dramatic… There’s a desk job with insane crunch expectations, minimal effect on the final product, and no unions on one side, and creative freedom but only maybe scraping together enough to supplement a totally unrelated day job on the other, and like, the frayed remains of a rope bridge in between. When I see the variety of work out there I’m energized, but being optimistic about whether this work will be taken seriously and get support so that it’s sustainable for people and not just something they do for 3-4 years then burn out will take a lot of political change, as well as a change in attitudes about the form.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ “Manifesto for Maintenance Art”

What makes something a videogame? It’s really just a set of things you can make a computer do that is largely defined and upheld by the interests of these huge companies! Think of how much control Nintendo likes to have over how everything about their systems, the games that run on them, the gameplay and the characters are depicted. And individuals are making work that’s obviously in conversation with that history, they’re also “videogames,” but the work that pushes at the edges or is unconventional in a way that makes me reconsider the classification of videogame at all, that’s what inspires me. As long as I still see stuff like that I will have a little optimism!

Thanks Emilie!

Some of Emilie’s Zine Work

You can dive into Manifesto Jam yourself here, and keep up with Emilie’s future projects and creative work on Twitter, Itch, and her website. Find a favourite Manifesto? Let us know in the comments!