I’ve never been a big fan of dating sims or visual novels, except where glimpses of those genres lined up with the romance subplots of games like Knights of the Old Republic or Mass Effect. The Persona series carried me a little further into the outskirts of the genre, but that was about it. However, the acclaim for Doki Doki Literature Club made me think: sometimes it’s good to try something different.

And that’s where my adventure began.

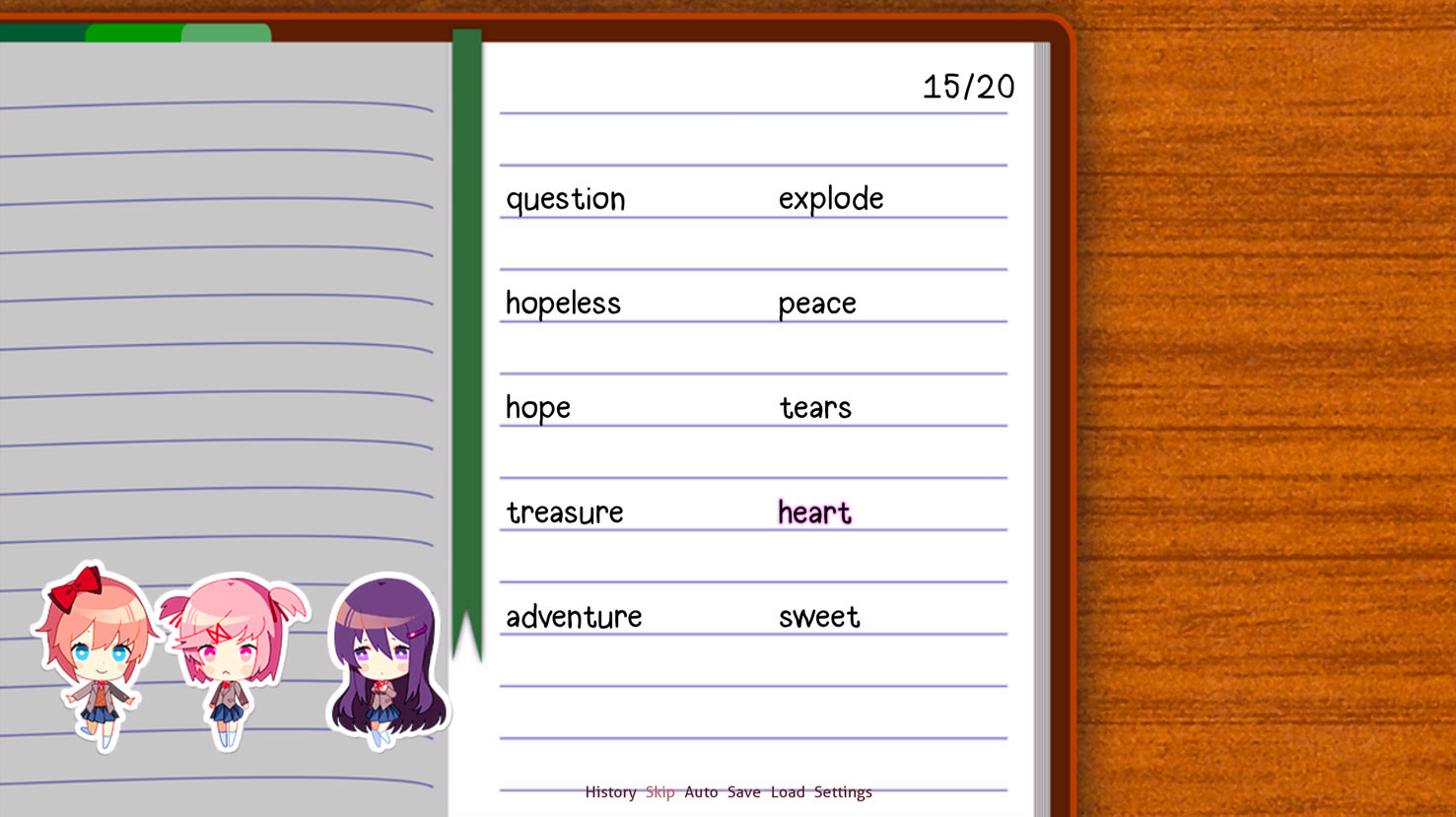

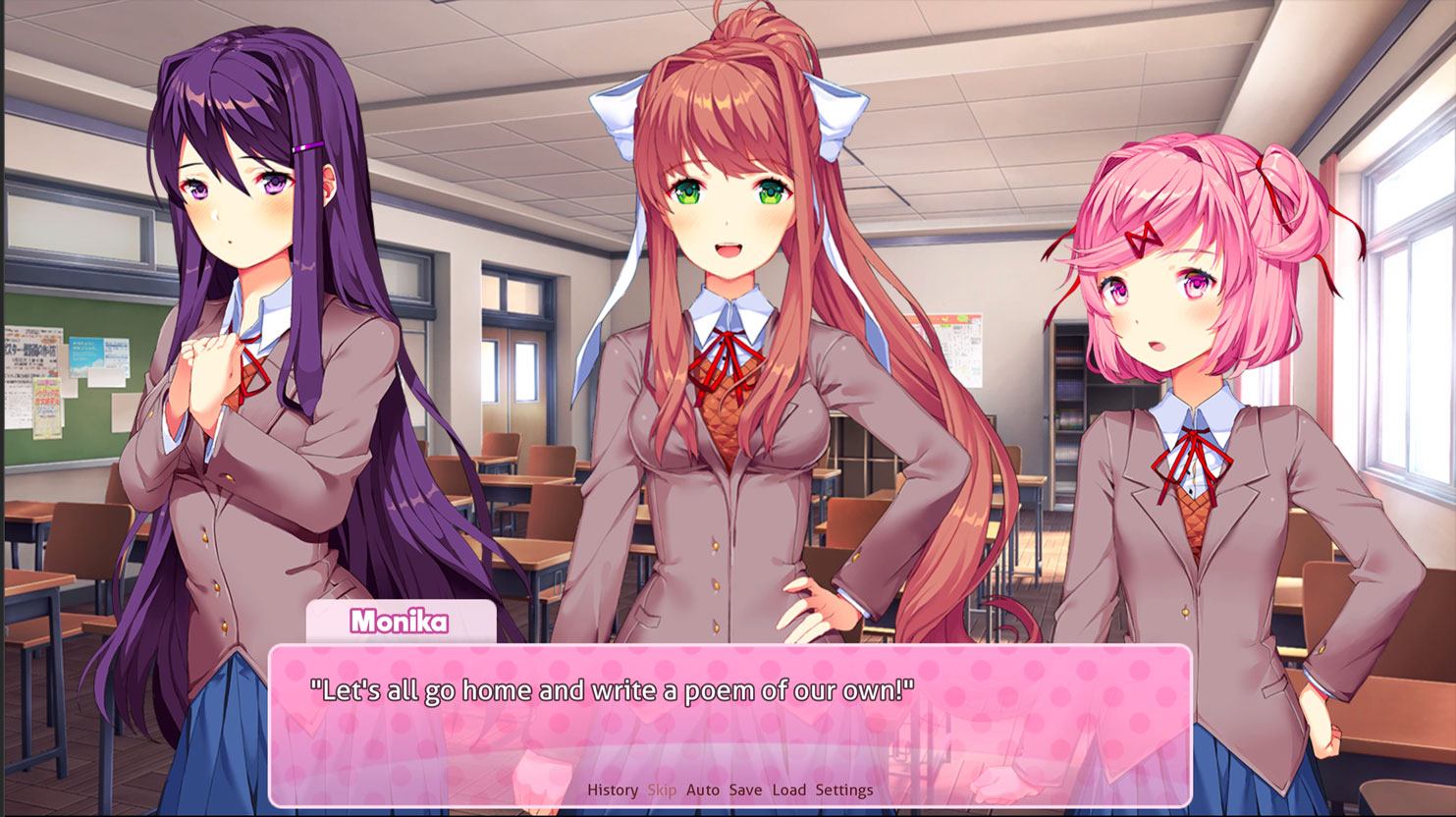

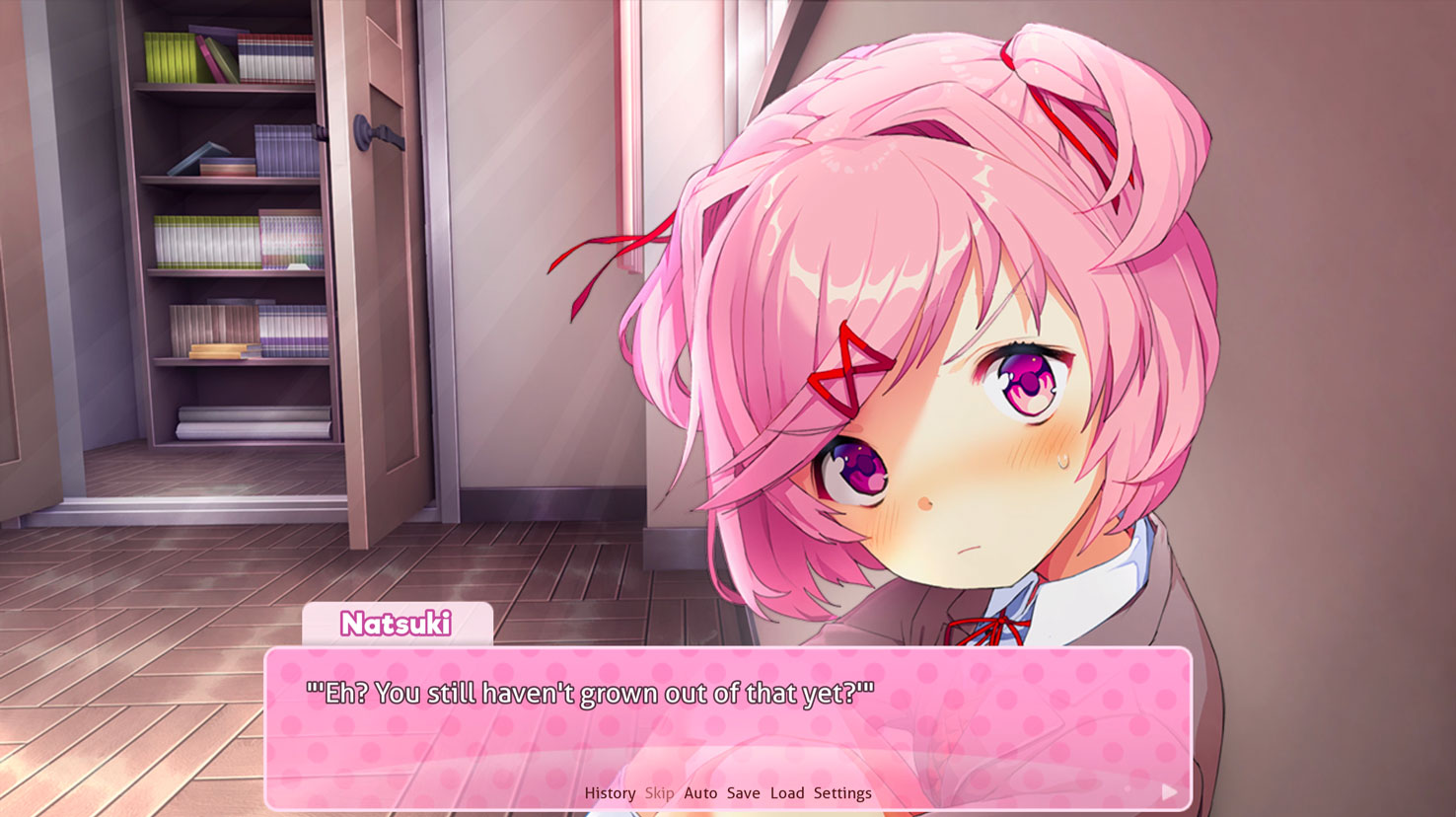

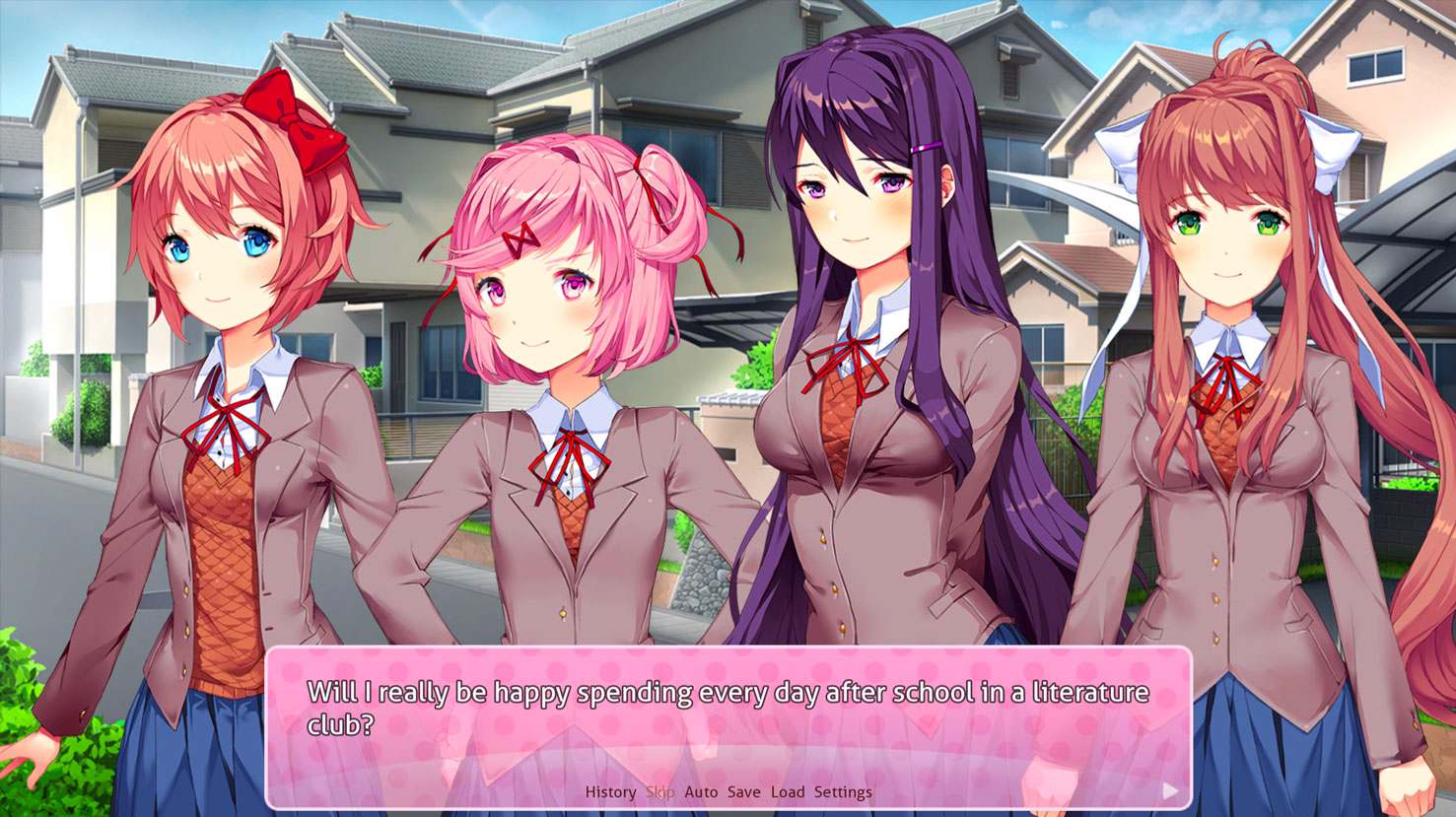

Doki Doki Literature Club features a cast of four high school women and one faceless male protagonist. Plot events lead the protagonist to join the titular Literature Club and you can pursue romantic interests by composing “poems” that ask the player to select keywords that appeal to one of the characters.

From there, I found myself a little surprised at the lack of decision points throughout the narrative. For the first act I was entertained but I mostly scrolled impatiently through walls of dialogue text. The second act, though, quickly became interesting and without spoiling too much, it’s understandable why this game has risen to the top of its class in many “Best of” lists for 2017. The narrative takes a distinct turn toward genre deconstruction and a meta-awareness that has increasingly crept into more games this year.

Pushing an Open Source Engine to Its Limits

Built in the Ren.Py open-source visual novel engine, Doki Doki Literature Club is an impressive feat of coding for reasons that are better left unspoiled. The poetry mini-game showcases the versatility of the platform, but in the second act, I found myself impressed by the way that the game specifically invokes its source code. Doki Doki is a game that doesn’t necessarily wow outright in its visuals—though they’re finely crafted—but it impresses through its attention to detail. The music cues, in-program animations, and jarring transitions work together in a way that made the narrative particularly enjoyable, even in the midst of horrific revelations.

Again, if there’s one clear place where it might seem like the game falters, it could be in the lack of decision points presented to the player throughout the game. Yes, there are meaningful choices to be made, but often they are few and far between.

In the end, it might be more to the credit of the designer that the player isn’t bogged down by a lot of meaningless decisions that wouldn’t directly influence the conclusion. Instead, the game forces us to consider: How do our choices influence those around us, and to what extent are we prey to the cultural “coding” that often constrains us in our everyday lives?

Yeah, it’s another game in the sub-genre I like to call: “So you’re having an existential crisis…”

While attempting to preserve as much of the plot as possible, I’ll just say that Doki Doki succeeds precisely because it does concern itself with agency—both that of the player and that of the digitized representations of humans that are coded to fall in love.

While it could certainly be argued that there are a few ways in which the game doesn’t quite go far enough in deconstructing its chosen genre, that mostly results from the inclusive message that we should feel comfortable to enjoy what we like. Certainly not a bad message, but one which could come into a bit of conflict with the commodification of women as a whole in a genre that easily veers in some uncomfortable directions.

Who’s Really in Control?

Doki Doki Literature Club prompts us to ask: does our freedom of choice extend to decisions that harm others? That’s the question that stuck with me long after the end of my playthrough. A dating simulator really only influences the strings of code that determine the behavior of the characters within the game world.

You’re not truly harming one character by pursuing a relationship with another, right? But, as an example of a growing body of games that emphasize the procedural nature of games and life, it’s not a far stretch to extend some of these principles into the real world. Sometimes there simply isn’t a “right” way to comfort another person, and that ambiguity is occasionally difficult to explore in a more linear medium.

In what way are we all constrained by the cultural and societal frames that we inhabit? And how do the choices we make invisibly affect the others around us? Throughout its relatively short run-time, Doki Doki Literature Club works to make the player identify with the four love interests while also distancing them from that reality by defying the standard expectations of a visual novel.

Doki Doki Literature Club might stand apart from its genre kin because of this thematic deconstruction, but it certainly has company. It’s hard to play through this game and not recognize the influence of other genre-bending narratives that equally highlight a game as a game. Undertale and The Stanley Parable come to mind despite sharing little more than a common focus on the agency games present players.

Doki Doki Literature Club might stand apart from its genre kin because of this thematic deconstruction, but it certainly has company. It’s hard to play through this game and not recognize the influence of other genre-bending narratives that equally highlight a game as a game. Undertale and The Stanley Parable come to mind despite sharing little more than a common focus on the agency games present players.

Pros

- Successfully deconstructs the dating sim genre

- Impressive coding: seriously, if you’re familiar with Ren.Py as an engine, you’ll appreciate the savvy on display

- Great mix of visuals, sound, and text

- Grapples with big questions about agency

Cons

- Grapples with big questions about agency, but doesn’t go far enough in some instances

- Short runtime and limited replay value

- Relatively few decision points

Conclusion

There’s a fun experience to be had with Doki Doki Literature Club if you’re in the right frame of mind. An impressive feat of coding for a free game based on a popular open-source Visual Novel engine, Doki Doki Literature Club simultaneously meets and transcends the boundaries of its genre.