When I first began playing The Long Dark, the idea of “organic narrative” kept popping into my head. I touched on it in an article about Wintermute, the game’s actual story mode. In that piece, I contested that the need to survive (and the inherent story of surviving) trumped anything the game offered in terms of curated narrative.

The premise of the term “organic narrative” as it relates to The Long Dark is as follows: there’s something about the game that makes it highly conducive to user-specific storytelling. But what makes the Long Dark’s story-free survival mode so good at telling a story?

Permadeath plays a large part in magnifying the finality of the player’s experience, but there is more to it than not being able reload a save. The answer, I believe, lies in Aristotle’s theory of tragedy.

Aristotle Has a Lot to Say

So, a couple thousand years ago, Aristotle is sitting around eating grapes, reflecting on the meaning of life or something. He decides he needs to write a treatise about the theory of poetry and drama. Presumably, he’s the go-getter type, because he does just that and he calls it Poetics.

Aristotle argues that a compelling tragedy is defined by six concurrent elements: spectacle, plot, diction, melody, character, and thought. If we take a look at the Long Dark’s survival experience, we can see that all of these elements are present.

The first four are built into the game, providing a framework for the player that all but begs for a story to be told. The other two, character and thought, are unique elements provided by the player. They are as much a product of the player’s life experience and character as they are a result of the game itself.

Spectacle

Aristotle believed spectacle, or the visual aesthetic of a play (or video game, in this case), was the least important of the six elements. It’s still very important, though, in the case of The Long Dark. The game’s color palette is bleak and washed out. Trees are bare. Buildings are burned out and charred black.

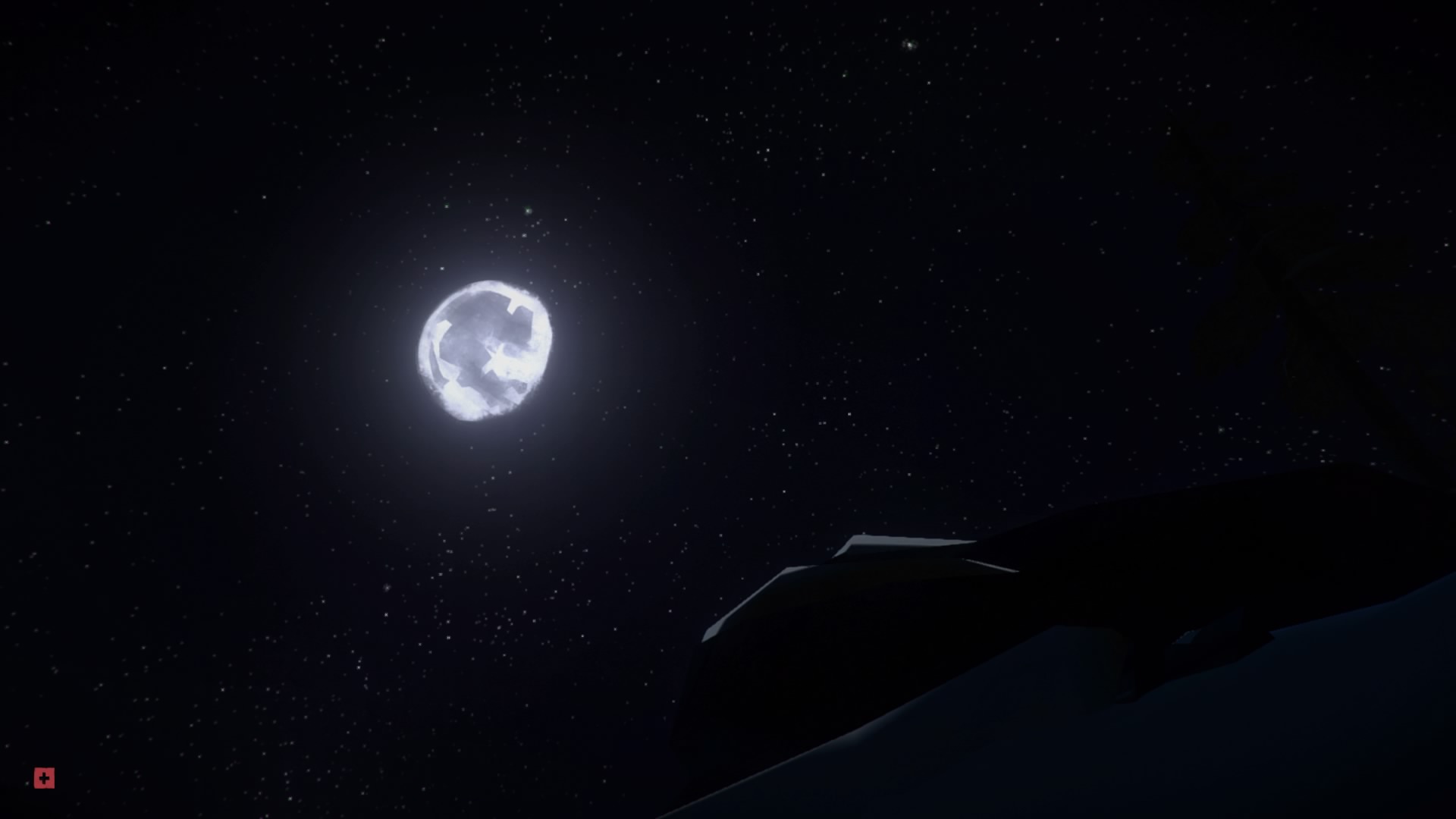

The only notable exception to this aesthetic is the skybox. A clear day or a moonlit night are godsends, beacons of the faintest hope in a cruel world. Sunrises are magnificent distractions that are almost always screenshot-worthy.

The aurora, when it arrives, is presented like its real-life counterpart: as a vibrant and captivating display of color, ribbons of deep green with red and purple fringe arcing across the night sky. But even in this case, the aurora presents a dramatically heightened level of danger as Great Bear’s predatory fauna become manic and hyper-aggressive.

Nearly every aspect of the Long Dark’s visual presentation carries a McCarthian weight of hope against hopelessness, of the player’s will to survive in spite of death’s unceasing pursuit.

Plot

Aristotle believed that a tragic plot was founded on action, rather than the growth of a character. Developer Hinterland represents this element well. The Long Dark’s survival mode features exactly zero character growth and a whole mess of action.

The player finds themselves in the wilderness of Northern Canada with very little in the way of resources. They must hunt, forage, pillage, and craft to maintain themselves. Eventually the player dies.

The player may grow from this experience, but the character does not. I’m not talking about leveling up your cooking. I’m talking about taking something away from the experience, using one’s newfound knowledge to overcome adversity and prevail.

There is some flexibility, here. The player is free to determine their own goals and plot in the interim, but the beginning and end of the story are set in stone and everything in between is action. We’ll delve further into this flexibility in a moment.

Diction and Melody

Speaking of determining your own plot, the diction and melody of the Long Dark play a large role in providing the impetus for action. We can equate this call to action with progressing the plot of the player-driven narrative.

I know, I know. Those two sentences are obnoxious. Let me elaborate:

The player’s avatar doesn’t talk much, but won’t hesitate to grumble when injured or hungry or, you know, freezing to death. A murder of ravens will caw as they pass overhead, signaling a change in the weather. The snarl of a wolf informs an impending attack. The wind whips and whistles outside whatever shelter the player has holed up in, telegraphing the danger of the storm outside. The occasional ambient music piece reminds you that survival is a temporary condition.

These are the sounds of the Long Dark, the melody of survival, the song of Great Bear. They each drive the organic narrative in their own way, pushing the player to act, to move their story forward.

Character and Thought

Character and thought, in terms of Aristotle’s theory of tragedy, can be taken almost literally. In The Long Dark, the player is the character, and their thoughts provide the justification for their choices. These elements are the domain of the player, shaped by who they are and what choices they are required to make on their journey.

Aristotle believed that character was the second most important element of a tragedy, and that seems to hold true in the Long Dark. This, I believe, is the crux of what makes the organic narrative so powerful in the game. The call to action, as described above, is constant. Despite this, there is rarely a moment in which it is clear which action is best.

A player spots a deer, for example. They may choose to kill it with a rifle. Maybe they’re hungry. Maybe they’re just thinking ahead, trying to gather resources while they can.

That bullet is a precious resource, but is it more precious than the crafting items and food that the deer will provide? Is it worth the weight the player will have to carry or the predator-attracting odor the raw materials will emit? Will the weather turn? Can they navigate back to safety if visibility diminishes? None of these questions have concrete answers until it’s too late, but the wrong choice can be deadly.

Everyone Has a Story

Four elements provide the framework for these choices, shaping moments of action into story structure. It is the player’s that define what direction the plot takes in and after that action.

There is a strong sense of ownership in that relationship. Each playthrough is a story acted out by the individual, highly unique despite the game world and mechanics never really changing much. Most people aren’t going to go out of their way to share their journey, but it’s there on every survival attempt.

Everyone has a story. The Long Dark is just really good at giving you the tools to forge that story.

If you’re interested in discovering your own stories, you can play the Long Dark on Steam, Xbox One, and PS4. For more Cliqist coverage of the Long Dark, check out this handy list.