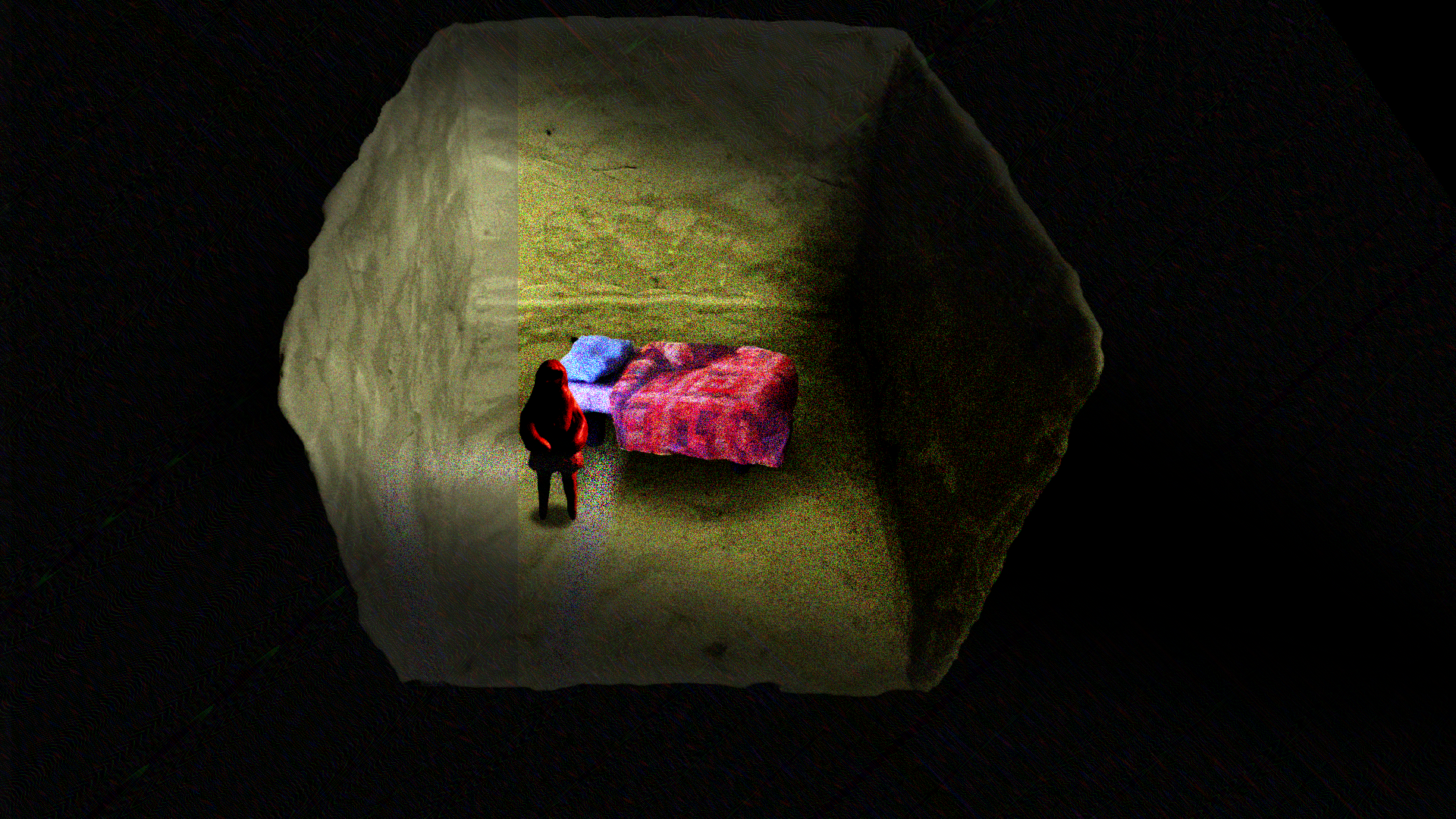

Dujanah slips into a windowless room with purple walls, and a soft piano ballad named “Mothers were all darlings” begins to play.

What of footprints? A grounded falsetto asks. What of satin? of tea-stains? kindling? nail files?

Seven expectant mothers sit in a circle, and I realise that the same games that normalise mutilation have made the image of a pregnant woman seem like a shocking transgression.

Man from Clay

It’s tempting to see these clay models as an abstraction. All swollen bellies and tiny pink breasts I imagine their creator shaping between thumb and forefinger. After playing, I discover their resemblance to a Dynastic Egyptian statue of a bird goddess. Later, Dujanah’s developer Jack King-Spooner will assure me that this is a coincidence. “They’re loosely little Henry Moore people.”

“All art should have a certain mystery,” Moore explained. Announce a work too explicitly, and the spectator makes “no effort to ponder the meaning.” I stand in this room, challenged by a sonorous, disembodied voice to consider nail files and pencil sharpenings and love bites. Suddenly, mystery seems obtuse.

Set against these concrete images, thematic metaphors seem flabby, transient things. Seven expectant mothers sit in a circle, in a small village, in the middle of a war zone, and that is all this needs to be.

Prufrock considered disturbing the universe, but he still measured out his life in coffee spoons, like most of us.

Military March

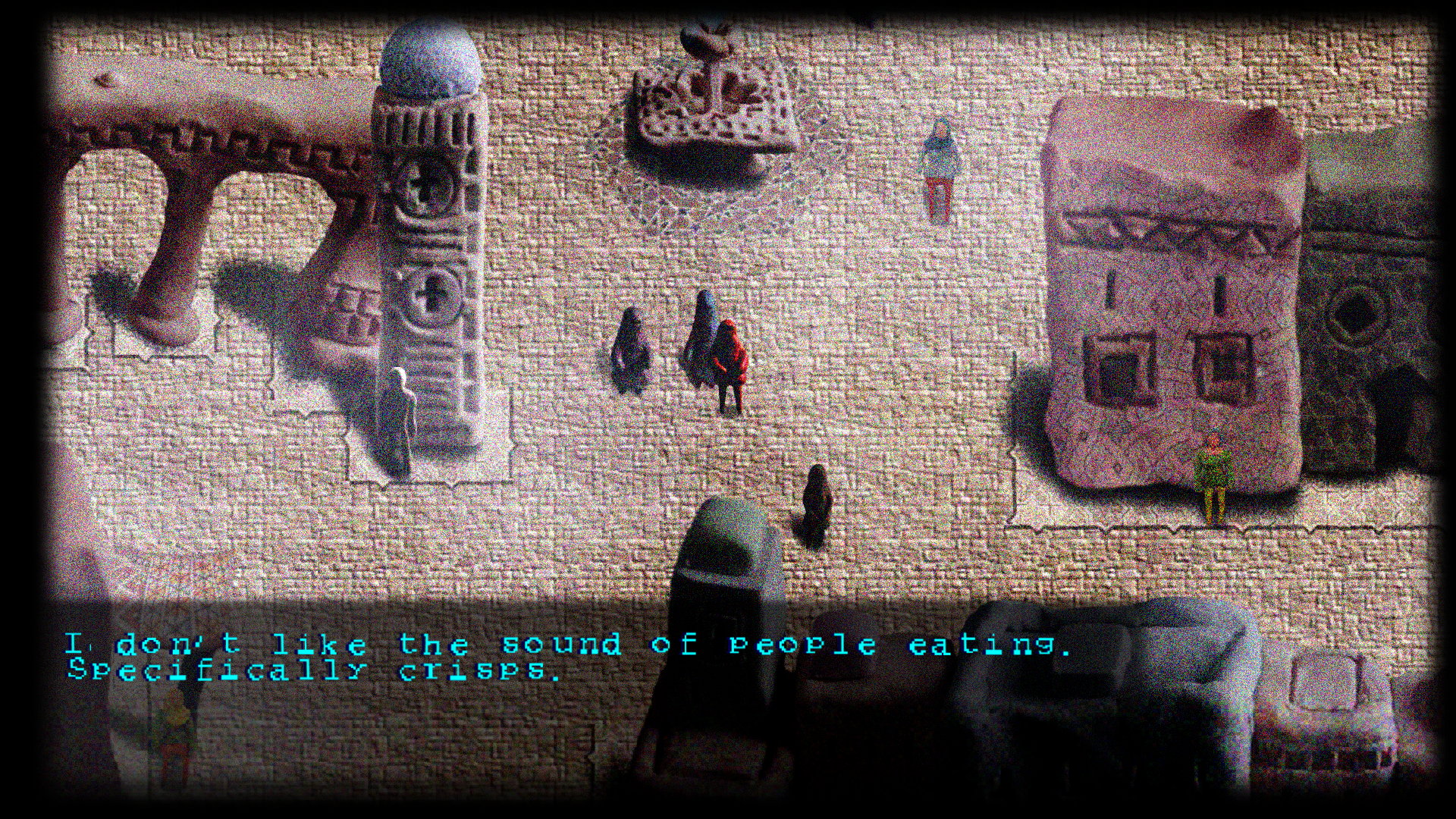

There’s a military base not far south from Dujanah’s home. It’s the first place I went looking for her missing husband and daughter. Here, the televised noise and heat glow mingle in bleak screen burn. Flickering static bleeding out from deep gashes in the concept of fidelity itself. Constant, homogenizing static, like an occupying army of furious ants.

The soldiers are shadows armed with automatic weapons and grim, glib quips. This place made of clay and wire and twigs may be the most honest military base a game has ever demanded I believe in.

Martial snare drum rolls ground this place in jingoistic familiarity, but their dignity is submerged under weeping, remote organ synths. If the drums announce the colonizers, then the haunting harmonics are the resistance. They mute the brass that heralds poisoned freedom, refusing to let this militia march retain glory.

This place is stripped of American exceptionalism. Stripped of the violent heroism that the rote aesthetic of gritty realism mistakes for hard honesty. There is only melancholic, nightmarish truth here. A real desert as stark panacea to the modern military desert of the real.

Speechless

As she walks through the base, Dujanah is unarmed, but fearless. She couldn’t exist in a game centered around conflict. Her presence would jam the signal too hard. Mangle a power dynamic that only facilitates threats, allies, and victims.

Dujanah slips behind the podium, and she is attacked by words and noise. Violent distortion like butchered robotic pigs matches the butchered syntax of the speech.The longer I read, the more the stitched-together rhetoric unravels, like the thread that keeps a soft toy’s button eyes sewn on.

It’s not subtle. Neither does it need to be, because it’s unequivocally about something. It recognises that the normalised image of this place is the fiction. There’s a gift, here; aggressive dissociation from the photo-realistic illusion of mass market military fever dreams.

Familiar Fiction

That mystery that Moore spoke of; that veil draped over a work that covers up the sharp edges, beckoning the observer closer – that’s defamiliarization. The words of Viktor Shklovsky, who coined the term, mirror Moore’s own:

“…the device of art is to make things ‘unfamiliar’, to increase the difficulty and length of their perception, since the perceptual process in art is valuable in itself and must be prolonged.”

So when the familiar is, in itself, a fiction – like a canon of games that only concern themselves with Muslim culture when they need an easy enemy to vilify – defamiliarization becomes a weapon against politically-charged abstraction, even as it abstracts.

Conjuring Empathy

This all sounds very serious, and I don’t mean to underplay how straight-up weird and disarmingly funny Dujanah is. I think this is where it draws its power though. Quirk, for Call of Duty, means Captain Price’s mustache. Gritty realism can vibe with superficially odd flourishes, providing they never dilute the melodrama. Dujanah has enough faith in the humanity on both sides of the screen to let its guard down. Odd or gross or mundane touches conjure empathy more powerfully than the longest rumination on otherness.

Punk bands in dark rooms. Small talk. Poop jokes. Dujanah recognises the alienating nature of constant profundity. Its vibrant, arresting idiosyncrasies reacquaint the player with the heart of the stories that make it what it is.

Gritty realism erases the delicate touches that define human experience – like polishing a statue with a flamethrower. Dujanah asks you to consider nail files, pencil sharpenings, and love bites, then bares its soul without caution.

You can play Dujanah here, and find our interview with its creator Jack King-Spooner here.

[…] Dujanah (Critical Distance […]