Kickstarter is a great way to receive an injection of funds for anyone with a creative endeavor. With the platform’s rise in popularity, it’s coverage across the internet has expanded. The go-to platform for crowdfunding independent projects is as much an online shop for publishers as it is creators. This has become more apparent than ever, and more would-be developers are taking advantage of the coverage to sell their product to more than just potential Kickstarter backers.

Nearly two months ago we wrote about Kontrabida and their twice Kickstartered game, Rival Threads: Last Class Heroes. We spoke with the founder of the company, Leonardo Molar, who made no bones about the fact the two crowdfunding campaigns were more about marketing than raising funds.

“We received about $27,000 to $29,000 from two Kickstarter campaigns […] which is a very small fraction of the money we spent on thousands of billable work hours, a full soundtrack, hundreds of art and animation, sound effects and voice acting for Rival Threads.”

The studio ended up losing money on both campaigns despite surpassing their funding goals. Because of this, the five member team had to turn to freelance work to secure funding. Molar walked us through the early days of the campaigns, the start of development, how work ground to a halt, and how the company almost went nearly bankrupt before they could produce a single game. It all stemmed from one unnamed middleman who worked almost as the company’s agent for several years. We couldn’t say much about this middleman back then, but I was lucky enough to catch up with Molar again and hear more about it this time in Kontrabida’s history.

Kontrabida began freelance work before Rival Thread’s second Kickstarter. Their soon-to-be biggest client, the unnamed middleman, backed hundreds of dollars into the first campaign. They had already known each other, but it was after the campaign when he approached the studio with a contract for animation work in the Middle East.

“We have never created anime and none of us have experience working on full length animation. What we had however, were extremely skilled young people who could pretty much figure out anything if given the time and found the challenge tempting and saw the benefit the money would do for our projects. […] Not only did we have the option to make some real money that would be valuable to our projects, but more importantly, create content for an entire region with millions of people starving for high quality culturally relevant content.”

The team jumped at the offer. It was a high profile job, their biggest yet. The payment was their largest too, so much so that Kontrabida expanded by hiring more members. The company split itself into two teams, one doing the freelance anime work, and the other working on Rival Threads and preparing the second Kickstarter.

What the team created was a 15 minute sample anime which aired in several conventions and Japanese TV shows as “the first Arabic anime.” Molar showed me some promotional material for the anime, and I have to admit, I was impressed by it. It looked like something a high quality Japanese anime studio would produce if they produced content in the Middle East.

It was a huge success for Kontrabida. Rival Threads received the extra funds, specifically for the second Kickstarter which happened “around the same time.” The extra money and experience showed, as the difference between the two Kickstarter campaigns was like night and day. But that experience wouldn’t be credited for Kontrabida as per their contract, which Molar doesn’t considered a big deal.

Freelance work in independent game development is nothing new. You can see it in action yourself if you’ve played Game Dev Tycoon. Often large publishers will either stretch themselves thin or they don’t trust their own development teams, and they’ll contract smaller studios to work on either a part of a project, or even the whole thing. Double Fine’s own Kickstartered game, Broke Age, springs to mind. Over budget and understaffed, the company hired a third party animation studio (SuperGenius) to work on most of the animations for the game. It’s a rare, insightful look into game development shown in the Double Fine Adventure documentary.

The public never hears about this kind of work because the contractors rarely want us to know that these small, often inexperienced developers did the work. The reasons can vary. Here the publisher wanted to take full credit as a political statement, passing the anime off as an Arabic production despite the team being composed of a staff “from Canada, England, the US and the Philippines.” In these cases, the publisher takes all or the majority of the credit, pays the developer, and everyone moves on.

A lot of the developers don’t always want you to know what they worked on either. A lot of freelance work isn’t glamorous; it’s dirty, and sometimes embarrassing. There’s also a series of barbed wire fences in the form of NDA’s – non-disclosure agreements – that prevent them from saying anything publicly.

As the second Kickstarter wound to a close, it proved to be a bigger success than the first. It raised $24, 812, rushing past its initial $5,000 goal in days thanks to the improved art, animation, and gameplay features. Kontrabida was swimming in success and popularity, but not in cash Scrooge McDuck style. Everyone at the studio knew this wouldn’t be the case, and continued their plan of working on freelance contracts to fund the bulk of Rival Threads.

This is where the middleman cropped up once again. He backed this second crowdfunding campaign, bringing his total contribution to both campaigns to over $2,000. That wasn’t all he had for the developer though. He set Kontrabida up with several meetings and contracts in the Middle East. This included working with big Japanese publishers whom Molar did name, however he wishes them to remain anonymous. The deal was to have Kontrabida work alongside these publishers to localize content to the Middle East. They were also set up with big organizations in the Middle East creating advertisements. For the next several months, the Middle East would be Kontrabida’s stomping ground as they worked on games, TV series, and with the Red Crescent. They also did a series of paintings depicting local people in their day-to-day lives. The studio’s most popular work were a series of paintings depicting women in empowering roles, such as playing sports and working, something that was a big deal in the Middle East.

Animation was where Kontrabida was getting most of their freelance work, but that’s just one of several fields a game studio can work. Usually we think of game developers doing programming work, but along with that and animation, they sometimes dabble in writing, marketing, production, localization, and other artwork. They all pay to different degrees, something also depends on the amount of work that needs to be done.

All while this was happening, the original core team continued work on Rival Threads. The team also had time to work on a few animated shorts detailing the backstory of the game, called Puppet Master. Molar, with the rest of his team behind him, thought things were looking good.

“It was all a blur. It felt great at the time, I was genuinely convinced that I was securing our small studio’s future – we can now provide high paying jobs to everyone and comfort for their families. A promising future in games and animation. We had a small group that served as our core and we kept a small stable of freelancers that we called upon when needed, everyone was happy with the work and the potential opportunities.”

But, as you would expect, Kontrabida wouldn’t be on top of the mountain long. Not long after the successful conclusion of the Kickstarter, a key team member left the studio. Elegy Wong, the lead character artist, left the studio for “personal reasons.”

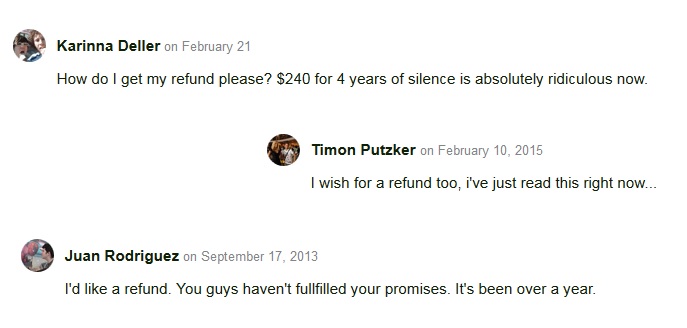

Because of this, and the increase in scope brought upon by the success of the Kickstarter, production on Rival Threads stalled. As is always the case after a series of delays, some backers lost their patience. To appease their fan base, they offered refunds to not just anyone who wanted one, but for every backer. Molar promised a refund “later this year [2014] or the first half of next year,” in a Kickstarter update.

For a time, it looked like Kontrabida’s amazing luck would save them again, but what happened next was the start of their downfall.

“The thing that set off this whole disaster was when our middleman was approached by a person from a “very powerful family” that wanted to create an animated movie.”

Molar was very candid with me about what happened involving this animated film. Because of this, his quote speaks for itself.

“I jokingly told them it would be impossible unless we had tens of millions of dollars at our disposal, an actual office (we worked through Skype, at the time), 10x the number of people we currently had and 3-4 years to do it. This is one of those rare situations where you hear “money will not be an issue” and actually have tangible reason to believe it.

“We had month’s worth of discussions and brainstorming with said person from so and so powerful family along with the middleman, we created some really crude pre-production stuff, ridiculously detailed cost-breakdowns that took weeks of planning and conversations with other professionals, plans and theoretical production schedules. They were happy, they wanted to take it to the next level – which would have been impossible with our current setup.

“The plan was for us to construct a team that would lead the project and have various outside studios involved in production. […] So I took the plunge, emptied my personal savings (earned through years of casual game-dev client work) for capital and infrastructure, the client doubled it and locked us down in a contract. I flew from Toronto to open a studio (which was basically just a really big apartment) in Manila (cheaper, more practical), along with a number of our artists, some of which I was meeting for the very first time, and we all moved in and worked together.”

This marked a turning point for the studio. For the first time, development of Rival Threads – while still being worked on – took a backseat to their freelance work. Or at least, it was supposed to.

That “next level” never happened though. As the team absent-mindedly scrolled through their phones in Manila, waiting for the final green light, this “powerful family” and their corporate financers couldn’t agree to terms. These financial backers, fed up with the negotiations, walked away for good. This “powerful family” assured Studio Kontrabida that the deal was still on if “they wait a few months.”

To keep his studio busy, Molar kept his core team working on Rival Threads. They released a demo in an August 2013 Kickstarter update that showed a drastically different game, one that featured better art and an overhauled, refined combat system. Updates were posted sporadically, showing off new player characters, new art, new features, and wishings of Happy Holidays. There was an update posted in July 2013 on the Kickstarter page with pictures of the team and the new “studio,” nothing more than a single apartment.

As months dragged on without anyone hearing from the “powerful family” or word on the movie, Kontrabida had no choice but to find a new major contract. They went back to their middleman, who set them up with several unnamed companies with increasingly short, poorly paid contracts, working on big name franchises.

“They would stretch out deadlines and budgets to the limit, letting us suffer, penalizing us and have us take the blame when things didn’t go as well as they promised their bosses. We had a project that was supposed to run 2-3 months last for 11+ months(!!!!) because of insane delays from clients, sometimes months or weeks because someone ‘went on vacation’ without letting us know.”

Molar was finding that the one common thread in these contracts was the middleman. He accuses this unnamed person of being “more focused on building relationships and rubbing elbows with bigger Japanese companies and personalities,” and says that he took credit for their work, something that cut deeper now that the team needed to build up their contacts.

The contracts kept getting worse, and the new companies Kontrabida worked with refused to adjust schedules, and that studio heads and project managers used “abusive language” and threatened them “casually.” One such threat came after a publisher asked for a minor change by telling Molar “if you were in this country, you would all go to jail,” regarding what was a scene lasting only a second and a half.

Contracts can vary wildly depending on who you’re working for, and what field you’re working in. Most companies are strict with their contracts, and have penalties and fees the material not up to their expectations or gets delayed. There are a lot of studios and individuals in Kontrabida’s position, needing freelance work, so big publishers have room to be harsh when it comes to their contracts.

One thing is for sure: freelance work isn’t fun for anyone. Most developers are stuck on projects designed to fill a hole in a market as opposed to being a fully creative endeavor, as evidenced by Kontrabida’s work in the Middle East. Developer Chris DeLeon wrote an article in early 2015 detailing his work as a freelance coder, having to make geography trivia games, a phone wallpaper app, and an advertising game. Before that, DeLeon worked on AAA console games, which goes to show that no is really safe from freelance work. It proves that Kickstarter isn’t always the end all, be all for a studio looking for funding.

In Kontrabida’s case, these contractors gave them a short leash, as described by Molar.

“Money that was owed to us either never came in full and was always weeks or months late, requirements were changed midway through projects, feedback and revisions given months after deadlines have already passed – delaying the projects by weeks or months and costing us tens of thousands of dollars out of our supposed ‘profits’, dealing with threats of ‘$XXXX penalty for every day you are late.’”

I asked Molar if he thought he was in any way at fault in terms of how the publishers were treating him. He made his position clear.

“We always, always completed our work, what choice did we have but work? Complaints, pleas and appeals met deaf ears. […] We worked with some companies that had people in charge who absolutely did not care about their properties at all.”

The studio eventually got so wrapped up in their freelance contracts, they had to dedicate all their time to them. The already small studio lost more employees, letting go the small team they originally brought in for contract work. With no end in sight, development on Rival Threads was put on hiatus in April 2014. An update revealed the news that month, and much like his interview with me, he was very candid.

“No excuses, I screwed up. […] This project has become very ambitious. It did not start this way. We are victims of feature and scope creep. The original plan was a fraction of what it is now. We were inexperienced and we overestimated our capabilities. We set our bar so high that we could no longer reach it, not with the resources we had. I underestimated the costs. I started working on this, treating it like a REAL job, when I was 22 or 23. Here we are, 4 years later and I’ve poured in just a little over $240,000 into this. Not just into this project exclusively, but the company, the people in it, our other projects, and the infrastructure we needed.”

The question of whether to leave the middleman and refocus instead on their own game development entered Molar’s mind. There was no way they could launch a third Kickstarter, not for Rival Threads or any other game after failing to deliver. NDA’s kept their mouths wrapped shut, and the fear of losing months of work without pay, or worse, was too great.

“We were wary of ditching our contracts, even though things were already going horribly wrong within the first few months, the money we would be leaving on the table and the time and money we already invested in people, equipment, relationships and facilities so we can take on these contract works was already in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. We would have been insane to bail out.”

But Kontrabida did ditch their contracts, months later. The final straw was one last contract, another case of Kontrabida not getting paid what they were owed. Molar confronted the middleman, but he was having none of it. He already wanted to move on to the next contract. After meeting his breaking point as he describes it, Molar felt he had no choice but to break away from this middleman and the various contracts they still had in place.

They freed themselves of the middleman in September 2015, having just broken even. After two successful Kickstarter campaigns, and over three years of freelance contract work, Kontrabida had nothing to show. They couldn’t claim their freelance work, bearing someone else’s name, and they hadn’t touched their own game in a year and a half.

They’re back in Canada now, putting together a website and a portfolio, hoping to attract new freelance clients. Yes, after all that, the studio is still looking for freelance work, because like so many other independent developers, they have no choice.

Thanks to their immense luck, or talent as they would rightfully prefer to think of it, they’ve got a few projects in the pipeline already. They’re working on two projects, one of which I was told is “pretty high profile.” These new clients are treating them much better than the previous middleman, and Molar expects the company to be back on their feet soon. In fact, when these projects are done, the company will begin to work on their own games again, including one that Molar says will be “way similar” to Rival Threads. When asked about the subject of Rival Threads specifically, Molar had only one thing to say. “Rival Threads will still be made.”

If nothing else, Kontrabida’s story illustrates the parallels of both freelance work and Kickstarter. They can build a foundation that allow a studio or individual to gain valuable experience and pay the bills, but they can also bring a studio to near ruin with terrible conditions, bad publishing deals, and unreasonably high expectations. It sheds a light on a side of the industry we don’t think about, and it shows that even with a successful Kickstarter, sometimes videogames can be more expensive than anyone can imagine.

Many will ask if Molar is being honest, especially those 827 backers over two campaigns. Despite his candidness behind the scenes, he was vague about what he wanted to put on record. How much of that is fear of the NDA’s and other contracts is up for debate. Without knowing who the middleman is, it’s impossible to hear both sides of this tale.

As I wrote about in our previous article, and he himself stated in the final Kickstarter update, he makes no bones about how he was over ambitious. Feature creep and a desire to make a game better than he had the funds for likely meant Rival Threads was doomed from the beginning.

Considering Leonardo Molar was 23 years old when he started this journey, I think it’s safe to cut him some slack, though maybe I’m blinded by my own lack of experience, as I’m 23 myself and also share the title of freelancer. We all make mistakes. Some might reconsider taking on freelance contracts after reading this article. Others will surely think Molar and the rest of his team are spoiled brats or whiners. That’s something Molar strongly disagrees with when I brought up the possibility with him.

“Not sure how this can still come up after some of our team members, myself included went months at a time without pay while still delivering work, and then just being asked to ‘move on’ or ‘not be petty’ after being shorted more than ten thousand dollars on a project or being told that we would be put in jail […] If I sound like I’m complaining, then maybe it’s because I just didn’t like that my guys had to borrow money to be even able to afford rent, disrespected, and then after all that hard work, get shortchanged and don’t even get a ‘sorry’, just a ‘move on’.”

No matter how you look at it, we shouldn’t define anyone by their mistakes. Molar and the rest of Kontrabida are determined to show they only make us stronger. Whether they succeed, and if they’d ever be accepted on Kickstarter again, is something only time will tell.

“No matter how ugly things turned out, I take solace in the fact that I have a group of now-ridiculously skilled friends that are motivated to go the distance with me. We did the whole corporate slave thing, it’s now time to do indie for real, it will take some time, we’ve been hiding in the shadows for three years, but we’ll be back making a lot of noise real soon.”

Awesome work on this Josh. Definitely a “grab some lunch and settle in for a long-read” article.

Truth, all the journalism awards to you good sir.

Thank you, it means a lot to hear that.

When you read an article like that. You’re happy to read cliqist. Still, it demands some thorough works, not everything anyone can do. Kuddos to Josh. A great read.

Ah, thanks a lot!

Wow this is one hell of a crazy story, unfortunately even after reading all of that, I can’t feel sorry for him. He should never have launched a crowdfunding campaign if he didn’t understand the details of the cost or the responsibility that his company was going to assume by launching a Kickstarter.

Besides it doesn’t look like the guy regret how everything went down. He’s just happy he got his skilled friends and team..not a word about those 827 backers.

Good point I don’t recall him saying anything about those backers in this article. All those years later, feel bad for those backers.

Yeah, I agree. In almost everything I’ve read on them backers still seem secondary to them.

[…] of its stuff you’ve likely heard before: the developer needed to pay the bills, worked on contract work, worked on other games, and helped […]