I don’t think I’m alone here when I say I saw my fair share of bullying as a kid, mostly on the receiving side. It’s not just that I was a gamer, but I was a sensitive, thoughtful geek. Oh, and I’m “not quite white.” This was the joke my brother and I have used to describe the way people of European descent ask us why we look or act a little different from how they’d expect. It’s led to all kinds of weird experiences that, as a kid, made me feel like an outsider. Within geek and game circles, I felt more accepted, but adding those to my heritage certainly kept me from being more mainstream. That’s why, perhaps, stories of outsiders always appealed to me, and Undertale takes that preference and runs with it in ways I never expected. Be warned, as this article will contain major spoilers.

Now, two things I want to say before I begin. The first is that I’m not some kind of victim here to rant. Don’t worry, this isn’t a “social justice warrior” article (though I never understood how that’s an insult), as I’m going to stereo-type a bit and that’s ok, it’s a cognitive tool we’re using only to make complex ideas more simple. We’re all capable of looking at the individual for who they are. At the same time though, I want to be clear that the world isn’t perfect. It never will be, but ignoring problems also doesn’t help balance things, which is the best we can reasonably hope for. I’m just one guy that loves games and loves when I can see how games can affect us without being heavy handed sermons.

If it wasn’t for the fact that I’m living in Japan, I probably wouldn’t have noticed this about the game. Part of this has to do with the player character’s presentation. As Jamie Madigan noted in a recent article, games can be the perfect place to see the Kuleshov Effect in action. The basic idea is that, when presented with a neutral face, the audience can be manipulated into believing different things about a character based on the context. Now let’s add in personal experiences. I’m currently living in Japan, a country where ethnic homogeneity is assumed as people around me speak in various Chinese dialects and most Europeans I meet are native speakers of French (I’m not exactly living in Tokyo!). Combined, Undertale‘s ambiguous hero(ine) says a lot to me. Let’s actually start from that.

The ambiguous gender of the main character is something that didn’t exactly hit me at first. Most games are about boys, and if it’s a girl, she’s generally hypersexualized or celebrated for being a girl in a man’s world. However, as I played through the game, I realized there was something not quite right. For example, in terms of gear, I could wear both a manly bandanna or a tutu. I dated a character that identifies as a man, but also a female character, though you may not learn until later that she’s possibly bisexual, if not a complete lesbian. Part of what makes this work is the player character’s ambiguous hairstyle, lack of voice acting, and blank face. This is also applied to the “first human” which we supposedly look similar too and is only referred to in neutral terms.

The ambiguous gender of the main character is something that didn’t exactly hit me at first. Most games are about boys, and if it’s a girl, she’s generally hypersexualized or celebrated for being a girl in a man’s world. However, as I played through the game, I realized there was something not quite right. For example, in terms of gear, I could wear both a manly bandanna or a tutu. I dated a character that identifies as a man, but also a female character, though you may not learn until later that she’s possibly bisexual, if not a complete lesbian. Part of what makes this work is the player character’s ambiguous hairstyle, lack of voice acting, and blank face. This is also applied to the “first human” which we supposedly look similar too and is only referred to in neutral terms.

For most players though, we write this off. “OK, so I’m playing as Pat. So what? It’s funny!” That was exactly my reaction and what started to get me to notice more about how the game functions to potentially include a broad audience, both by pandering to us and making fun of us.

If there is one tool you can use to make social commentary, it’s comedy. There’s a reason humor from decades past doesn’t always seem funny to modern people if you don’t understand the context. Abigail Jones wrote in her thesis on the use of Eddie Murphy’s “White Like Me” sketch as an example of effective use of social commentary through comedy that, “Comedy is like a social ninja. It distracts you with the safety and the good feeling of laughter and then out of nowhere it hits you with a roundhouse kick of criticism. Comedy does much more than entertain an audience.” However, younger readers may not be able to appreciate the full effects of that skit without a history lesson or two.

In order to be effective though, the audience needs to feel they’re on the same level as the comedian, but not just in terms of power. As Jones notes, the joke can be funny without knowing the context, but it doesn’t have the same impact. Once you know it though, not only can you at least passively understand the deeper meaning behind the joke, but I’d even argue that it makes the joke funnier. White people having parties on a bus after a black people leave it is funny, but when you know about the history about how black people were treated on the bus in the 1950s, the absurdity that the gap was so big that parties might be thrown when blacks weren’t around makes the sketch more amusing. We can see that in this game as well though.

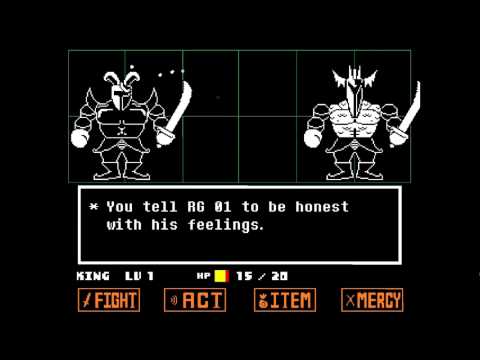

Take for instance the two royal guards you’re forced to fight in Undertale. If you go the pacifist route, you make one guard take off his armor to apply pressure to the other guard to get him to come out. If you were raised in a culture where homosexual love is seen as normal, this becomes a little less funny. However, let’s be honest: most of us aren’t living in that culture. Initially, we don’t laugh because they’re gay, we laugh because we don’t expect these two guards to fall in love and go out for ice cream rather while on the job. The underlying fact that they’re apparently gay doesn’t have any greater meaning until you realize that, if you’re a male doing a full pacifist play through, you the player have already gone on a homosexual date (ladies might not realize this till a little later in the game, most likely during their second time through). The game isn’t making fun of homosexuality at all, but points it out and almost normalizes it by having a consistent presentation of playfulness among the couples (even if someone’s wife is mad at him for killing some humans).

Take for instance the two royal guards you’re forced to fight in Undertale. If you go the pacifist route, you make one guard take off his armor to apply pressure to the other guard to get him to come out. If you were raised in a culture where homosexual love is seen as normal, this becomes a little less funny. However, let’s be honest: most of us aren’t living in that culture. Initially, we don’t laugh because they’re gay, we laugh because we don’t expect these two guards to fall in love and go out for ice cream rather while on the job. The underlying fact that they’re apparently gay doesn’t have any greater meaning until you realize that, if you’re a male doing a full pacifist play through, you the player have already gone on a homosexual date (ladies might not realize this till a little later in the game, most likely during their second time through). The game isn’t making fun of homosexuality at all, but points it out and almost normalizes it by having a consistent presentation of playfulness among the couples (even if someone’s wife is mad at him for killing some humans).

Think of the dog couple couple you fight in Snowdin. As a pacifist, they also work closely as a team and show affection through nuzzling during the fight. You trick both of them into thinking you’re a puppy that pets other dogs and, like the gay guards, they wander off, their minds apparently expanded. The same later becomes true of two of your friends, an unlikely monster couple with an obsession over human anime, something we wouldn’t expect from a warrior or mad scientist.

But let’s pretend for a minute that you don’t respect this perspective. Let’s pretend you laugh because the characters are gay. That’s fine! That’s step one to acceptance. Like white supremacists laughing at Chris Rock jokes about other black people, enjoying the joke, referencing it, and passing it on makes it part of your culture. You are still promoting the cultural vehicle that carries the message forward and gives people the chance to recognize it for what it is. Chris Rock criticizes poor representatives of black culture, and the racists pass on that criticism. It may strengthen their racism, but it also spreads black culture. A homophobic person who loves Undertale but can laugh instead of being repulsed by gay characters sends the message that games can at least include homosexual characters.

And that’s the beautiful part of the game’s humor. It’s these characters, these weird, fat, skinny, stupid, clumsy, geeky, weak people, doing funny things, make us laugh with them. The bullied taking ownership of their differences through comedy empowers them. We, the player who’s been exploring our own identity, can laugh with them. Before we laugh at the guards, we most likely have laughed at ourselves because we’ve gone gay for Papyrus by this point. We’ve worn a pretty ribbon, rolled around to smell like puppies, and wiggled our hips at goo. Most of us, at this point, are weird, and we love it, and since nearly the entire cast of characters are weird, they love us too. Toby Fox, the game’s creator, has even mentioned that the idea is that the player puts themselves in the game

https://twitter.com/fwugradiation/status/643945593308618752

That shows that the game is clearly meant to be a personal experience and that the player is meant to associate the main character with them self. Not only does that say a lot about inclusion, but speaks volumes about player identity, but I’ll leave that for another article.

Now, some of you are going to jump in at this point and say, “Well, what if I killed everyone?” That’s a legit argument. After all, the game has both the comedic pacifist side and the genocidal, literally-kill-everything side. However, even in a genocide run there’s still comedy, though it’s a bit dark. When you have to battle Papyrus, it’s quite different from the pacifist route.

Despite obviously being disturbed, Papyrus and other characters actually give you a chance to change your ways. You’re given several opportunities to go back to being a nice guy. If you’ve befriended characters in previous runs of the game, there’s even hints at that. The game has a deep metaverse where it remembers a lot of your actions, even if you don’t save, and it will use that to tug at your heartstrings. Yes, it’s used to blur the lines of fantasy and reality to create an internal, cross dimensional metaverse within itself, but it’s not just for fun. The game wants to redeem killers by remembering your attachments to its world.

Think about it this way. The true enemy in the pacifist ending will tell you to kill them. They’ll threaten to kill everyone you love if you spare them. And yet, if you show mercy, they don’t. They turn out to be a decent person, just someone who’s been alone and isolated for too long. Someone who’s longed to connect to someone else. I’m not a killer myself but I’ve been that hateful person. I’ve done terrible, indecent things to others. I remember my mother breaking down into tears a lot when I’d just show hints of how deeply I hated people. I don’t think I was a bad person per-se, and certainly not evil, but simply too afraid to show how lonely I was. Once someone connected to me and told me it was ok to feel that way, well, it started to go away.

Undertale‘s not real, but it has the power to really include us in its story. That’s one of the myriad reasons it moved me, both with the pacifist ending and the genocide ending. Nicholas David Bowman mentions in The Video Game Debate that while games can be seen as murder simulators training kids to be remorseless killers, recent studies “… have demonstrated this claim empirically, finding that when a video game presents gamers with moral transgressions, they will actively avoid the anti-normative behavior (such as committing an act of violence) or they will feel a deep sense of guilt if they do.” It’s one of the things that I think people really love about the game, and why I personally have a hard time motivating myself to do play through the genocide route, largely preferring to watch others.

Why does a game have this impact on us? The same reason mythology, fantasy, and sci-fi still bring up serious discussions about humanity. By using fiction to tackle stereotypes, we can distance ourselves from the real problem and safely explore it. Even now, we can see social commentary in the Harry Potter series. As Dr. Richardson notes in his speech, Elves and Werewolves and Voldemort! Oh, my: Social Commentary in the Fantasy World of Harry Potter, Rowling starts out writing for children, but expands her audience as the original readers are becoming older. The idea isn’t just to keep readers though, but to include more readers and safely bring up topics like racism and gender inequality indirectly by using fantasy creatures to stand in for real world topics.

Why does a game have this impact on us? The same reason mythology, fantasy, and sci-fi still bring up serious discussions about humanity. By using fiction to tackle stereotypes, we can distance ourselves from the real problem and safely explore it. Even now, we can see social commentary in the Harry Potter series. As Dr. Richardson notes in his speech, Elves and Werewolves and Voldemort! Oh, my: Social Commentary in the Fantasy World of Harry Potter, Rowling starts out writing for children, but expands her audience as the original readers are becoming older. The idea isn’t just to keep readers though, but to include more readers and safely bring up topics like racism and gender inequality indirectly by using fantasy creatures to stand in for real world topics.

Undertale does the same with outsiders. You’re the only human among monsters, your gender is ambiguously neutral, your sexual orientation seems rather flexible, and even your morals can be rather easily changed, as you’re allowed to play out both hero and, frankly, villain. No matter how you play though, the game knows it’s not a real world, but tries to blur the lines between fantasy and reality to dig its claws deep into you. Played nicely, the game draws out deep empathy as you sympathize with your fellow outcasts. When you choose aggression, the game calls you out on your monstrousness, making the “monsters” in the game more human and making you so heinous that they flee from you, all while the defenders of the game world try to give you the opportunity to stop your genocidal ways and, well, be their friend. Shy geek or lonely killer, Undertale wants you to include you.

Are you for real? You bring Chris Rock up as a positive example? Have you not heard about his last movie? That idiot is a homophobe!

[…] to mechanics, much like Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons did. While it manages to touch on some rather tricky subjects it is also a game that turns killing into an act worth thinking about, all while also managing to […]