I strongly hinted at this in my article about Undertale and including outsiders, Undertale performs so well because it engages its audiences. It’s not only trying to include outsiders topically, but it’s trying to include a broad audience and play with them, specifically by playing with their sense of self. Be warned, as once again, I’ll be going into spoilers in order to details just how the game plays with the player’s sense of self in a way mass produced games rarely do.

Let’s start off from the ending of the previous article:

You’re the only human among monsters, your gender is ambiguously neutral, your sexual orientation seems rather flexible, and even your morals can be rather easily changed, as you’re allowed to play out both hero and, frankly, villain. No matter how you play though, the game knows it’s not a real world, but tries to blur the lines between fantasy and reality to dig its claws deep into you. Played nicely, the game draws out deep empathy as you sympathize with your fellow outcasts. When you choose aggression, the game calls you out on your monstrousness, making the “monsters” in the game more human and making you so heinous that they flee from you, all while the defenders of the game world try to give you the opportunity to stop your genocidal ways and, well, be their friend. Shy geek or lonely killer, Undertale wants you to include you.

Now, as Ron Tamborini and Nicholas David Bowman have written, there’s something called “presence” gamers feel in their games. Socially speaking, it’s the way you feel you’re in a game as you. Call it immersion if you want, but the difference is that you can feel a sort of social impact by existing in that world. Jamie Madigan has also covered this topic, but what Tamborini and Bowman bring to the table (other than a lot of research) is the idea of games as a kind of training, simulation, or even therapy tool. By having a virtual presence in the world, the player can learn certain skills or even feel emotions that can be carried over into a real world context in ways other kinds of training/simulation/therapy rarely can replicated. Specifically, the decision making process available in many games simply isn’t available in other forms of media, such as television, making the outcome of your choices and your place in the world more mentally and emotionally tangible.

For example, after getting the true ending in Undertale by consistently choosing to resolve conflicts non-violently, the game, through your (former) enemy Flowy, once again appeals to you, the player. The game/Flowy asks you not to start a new game, despite the fact that it’s a game with multiple endings and variations depending on a lot of your actions. It says that, by restarting, you’re taking away everyone’s memories. Their happiness. Even the hero(ine)’s, who you were controlling for the whole game.

As a gamer, we’re used to obliterating that sense of ending for the cast. They’re fake, right? They’re like toys, but Undertale is going the Toy Story route of making our game/toys seem real, just like when we were kids. While I admit I’ve played the game a little more, I never did a true reset. I made other games on other devices, and I’ve never been able to bring myself to finish a genocide run. I actually felt too bad about my actions to do that, and there’s a reason for that.

As I briefly mentioned before, there’s been some studies on gaming and morality, and Undertale in particular seems to fit the description of a game that can be enjoyed while making you feel bad, even if it’s encouraging you to not play it. Should you actually go the genocide route, called so because you play the game as a traditional RPG in which you simply kill everything, the game actually may become more sentimental. In the true pacifist ending, we learn that Flowy is the trapped soul of Toriel and Asgore’s son, Azriel. He had simply gone astray it seems.

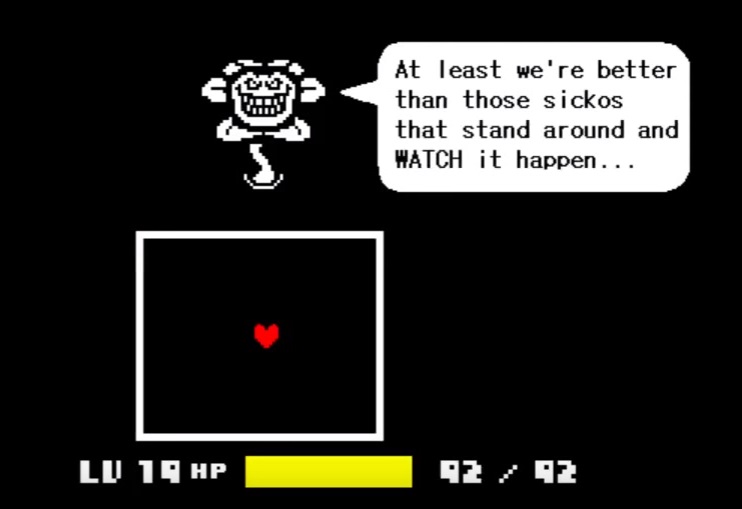

However, if you go the genocide route, Flowy seems… different. He talks about choosing to continue when he’s near death. He can reset, go back, do things differently. He tries to help people at first, and then… doesn’t. He tortures and kills. He’s doing things different just because he can. He is, essentially, a player in a game. Not just any player, but a hardcore fan trying to see it all, like many of us have been about one game or another. In fact, Flowy has even been recorded taunting players when the game is being streamed for not being as hardcore as he is.

This isn’t merely breaking the fourth wall. This is a direct call for the player to question why they play the way they do, and whether or not it’s really harmless. Are our actions just play, or are can living out these fantasies be damaging? It’s an accusation that makes the gamer question not just their play style, but the value of it. It makes us feel a bit guilty, but at the same time… well, the game still has a very high score on Metacritic, so apparently a lot of people have enjoyed it enough to give it a solid score.

However, Flowy can be redeemed. “Chara,” the first human, cannot. Should you finish the genocide route, Chara will allow you to “delete” the game world so you can move on and continue to be the kind of gamer that essentially destroys virtual worlds. I can relate to Flowy, as I’ve been the guy that has tried to do the bad stuff a million times, but eventually just tired of it. I’ve been redeemed. Chara, on the other hand, reminds me of players who see the moral choices and always chooses the worst one… and laughs about it. Not the “that was surprising” kind of laugh, but the “I love inflicting pain” laugh.

Even without playing the genocide route, watching it can be painful because we can remember our own experiences. The characters say “you” when condemning actions, and it can be hard to separate ourselves from that, even when we’re watching. The fact of the matter is that Undertale is an experience akin to playing house. We’re in a different world testing and teasing possibilities, and much like the kids we may play house with, we will be judged on our actions, which helps (or hinders) our ability to keep growing, not just as gamers, but at least as a member of the gaming community, if not society.

I don’t really care about inclusivity, but I do think that Undertale is one of the most important games in many years for one simple reason: instead of doing what movies or books do and just adding some form of interactivity, Undertale tries to use it’s medium to it’s fullest and tell a story that can only be told via interactive storytelling. That itself is admirable, but the fact that it succeeds as greatly as it does makes Undertale important. Writers for videogames should be forced to play and study it to learn how to tell proper interactive stories.

[…] conditions like most games (more on that later), it tells a story and allows for reflective moments to consider what one has done both in the game and as it relates to their life, which is exactly what Ebert constantly claims is […]

[…] is that the violence aspect comes out when you don’t have a system in place to correct it, like in Undertale. We have enough bad content out there without trying to make it “adults only.” […]