Aivi Tran is well known for working with their partner surasshu on composing the musical score for Cartoon Network’s critically acclaimed and Emmy-winning animated series, Steven Universe. Known together as aivi & surasshu, the two give the show a video game-influenced soundtrack, filling it with the hybrid sound of chiptunes and piano that evoke the feel of games like Legend of Zelda and Animal Crossing. But aivi & surasshu go beyond capturing the sound of games; the pair also score them, working on independent projects and minigames for Google Doodles.

Cliqist got in touch with Tran over email to talk about the various games they’ve worked on, collaborating with other musicians, and how they make the score in Steven Universe more interactive.

Aivi Tran and surasshu are a composing team that work together on various projects. They specialize in combining piano with chiptunes.

Cliqist: How did you get into composing music for games? What inspired you to enter this field?

Aivi Tran: My parents loved music and always had cassette tapes and vinyls playing in the house when I was growing up. They fell in love by singing Vietnamese songs together, and sang to me a lot. I think that constantly listening to music as a child primed me to be a musician. I begged my parents for piano lessons before I could read words!

Then I fell in love with Koji Kondo’s music when I was 10 years old, after my family got a Nintendo 64. My first foray into game music was figuring out how to play music from Super Mario 64 by ear on my piano. Around that time, we moved to a different country and I was separated from my piano for a few months. My new school offered a music technology class, so I signed up for that instead. I learned about MIDI sequencing there and realized that I could go beyond playing Mario songs: I could literally recreate those songs using digital sounds.

It was rare to find official CD releases of game soundtracks in my childhood. And we had dial-up internet back then, so if I pirated music, downloading a single song could take a whole day. So game music fans—many of them kids like me—learned how to sequence MIDIs and shared our transcriptions of game music though the Videogame Music Archive. By recreating those songs, I learned how game music was constructed and orchestrated. I listened to other people’s MIDIs and discovered soundtracks from consoles outside of my Nintendo 64. I studied so much game music that composing my own game-styled songs came naturally to me.

I love how classic game music manages to be emotionally evocative while being concise because of technical limitations. Game music spoke to me directly because of that and swept me away to other worlds. I wanted so badly to build my own worlds!

Cover art by Cryamore developer Rob Porter, featuring protagonist Esmy.

How would you describe the scores you create for the games Cryamore and Ikenfell, and the music you contributed to Soul Saga? How do they differ from each other? What influences them?

Cryamore’s music is very special to me because it was my first big soundtrack. All of my optimism and excitement spilled all over my songs! I related a lot to Esmy, the game’s protagonist: in the game, Esmy is tasked with her first big adventure and she’s eager to prove herself capable. I felt that way as a composer.

I established a hybrid chiptune/orchestral palette for the soundtrack, drawing inspiration from some of my favorite game music: Koji Kondo and Mahito Yokota’s music for Super Mario Galaxy, the Mischief Makers soundtrack by Norio Hanzawa, and the Legend of Zelda series. Some of the tracks in the game are songs that I had composed previously, repurposed from projects that didn’t make it to the finish line. I’m so grateful for Rob Porter and Alan Wansom [Cryamore’s creators] for giving me the opportunity and being supportive friends over the years. The early demos I did for Cryamore are what caught the attention of the Steven Universe team.

Though Soul Saga is still in development, its soundtrack is available for purchase, with cover art by Akaneko.

Soul Saga is Mike Gale’s love letter to JRPGs, so the musical direction was my take on JRPG music. The game takes place in a sky world, and the game’s artwork had a lot of natural textures and warm colors. I wanted the music to be humble and earthy, yet light and airy to match. I used an acoustic palette for my songs—instruments that you can play with your hands. I contributed a few early tracks to help establish a musical direction, along with surasshu and Pongball. But the majority of the music was written by Ryan Camus, who is an amazing composer! His songs are beautiful, rich, and uplifting, and he made the Soul Saga soundtrack into what it is.

Ikenfell is the first soundtrack that I’m working on as aivi & surasshu. The music is a blend of our piano and chiptune palette, with a touch of inspiration from Canadian folk music. One night while Chevy Ray [Ikenfell’s creator] was in town, he showed us “The Black Fly Song” by Wade Hemsworth and other folk songs that he grew up with in Canada. One of my favorite things about Ikenfell is how the characters all express different sides of Chevy, so I felt it would be meaningful to draw inspiration from the songs that he listened to during his childhood.

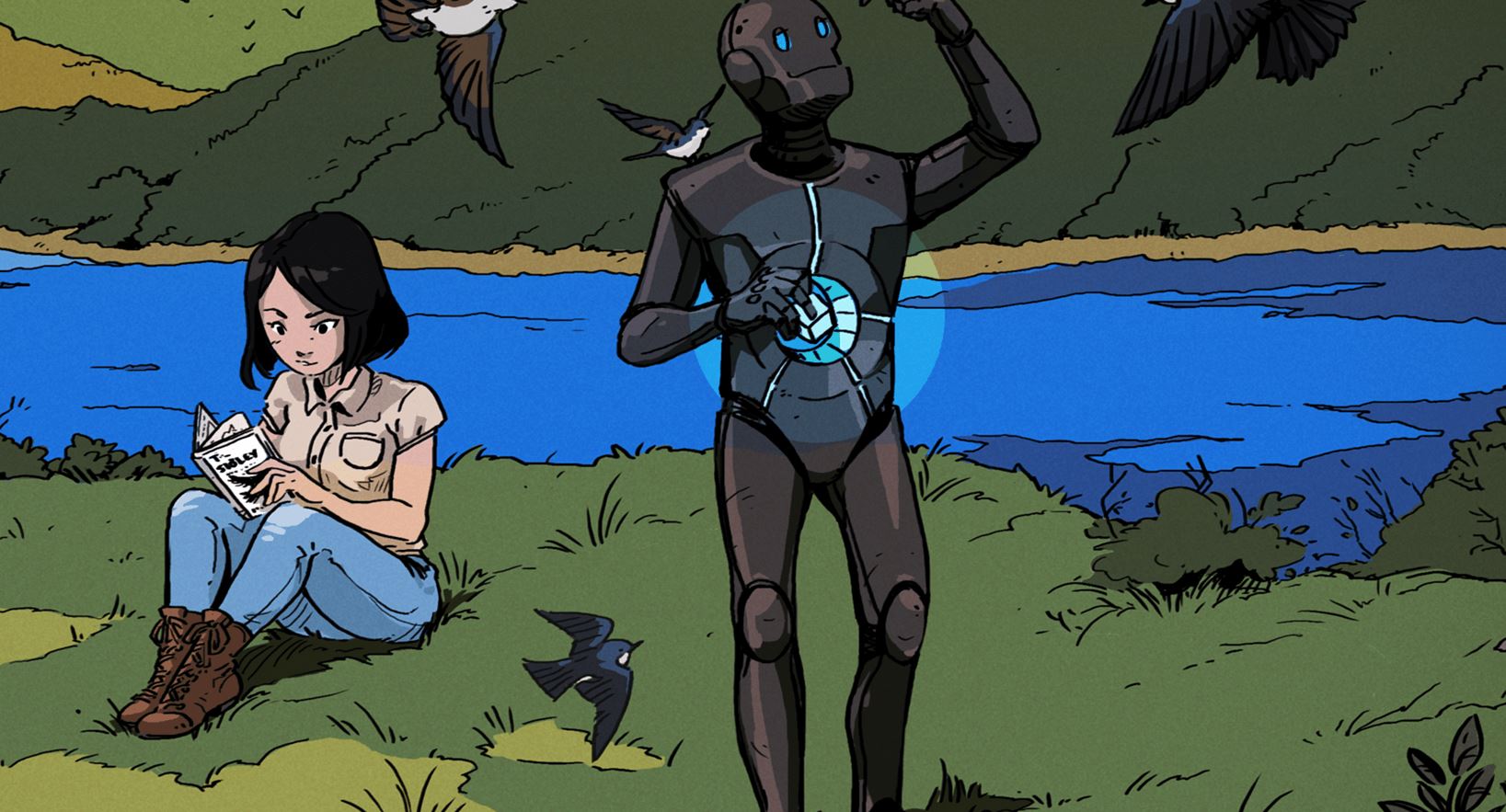

Promotional art for Ikenfell by Darcy Dee.

What was your process for these games? Did you use the same techniques for Cryamore, Ikenfell, and Soul Saga, or were there differences?

I use a standard home studio set-up: a computer, an audio interface, a MIDI keyboard, a pair of headphones, and two speakers. My keyboard has 88 weighted keys since I perform all of my piano parts and record line-in audio. I’ve been using the same keyboard for eight years now.

But my secret weapon is collaboration! I blend digital music with live performances and work with other musicians in the game music community whenever I can. I used to be more precious about my own work, but I’ve learned that when I let go of my ideas and make room for other people to contribute their genius, the songs that we make together become really beautiful.

Cryamore and Soul Saga used similar techniques. I sequenced the music in a DAW and incorporated live instruments where I could. Ikenfell’s music has been more complicated: we use DAW sequencing, live instruments, chiptunes that surasshu tracks using ChibiTracker, and we’re also working with lyrical songwriters and vocalists.

A screenshot of gameplay from Ikenfell.

Ikenfell is also more complicated because of the way we’ve chosen to approach the music. We’re combining game music composition with cue scoring, something we’ve learned through our work with Steven Universe. Since the game is story-driven, the narrative goes through many moods, so we’ve composed a lot of smaller, ambient pieces to complement those emotional beats. It’s meant to feel like you’re watching a show.

How does making music with a partner like surasshu work? Does it remind you of the cooperative aspect of play that can happen in games?

surasshu and I play games together a lot, and it’s similar to how we make music! We’re kind of cooperative-competitive. I think we make a good team because we have different approaches to the same goal, so we cover each other’s blind spots. But it also means that our synergy can be a disaster. I love both gaming and composing with surasshu because the result is always fun and interesting!

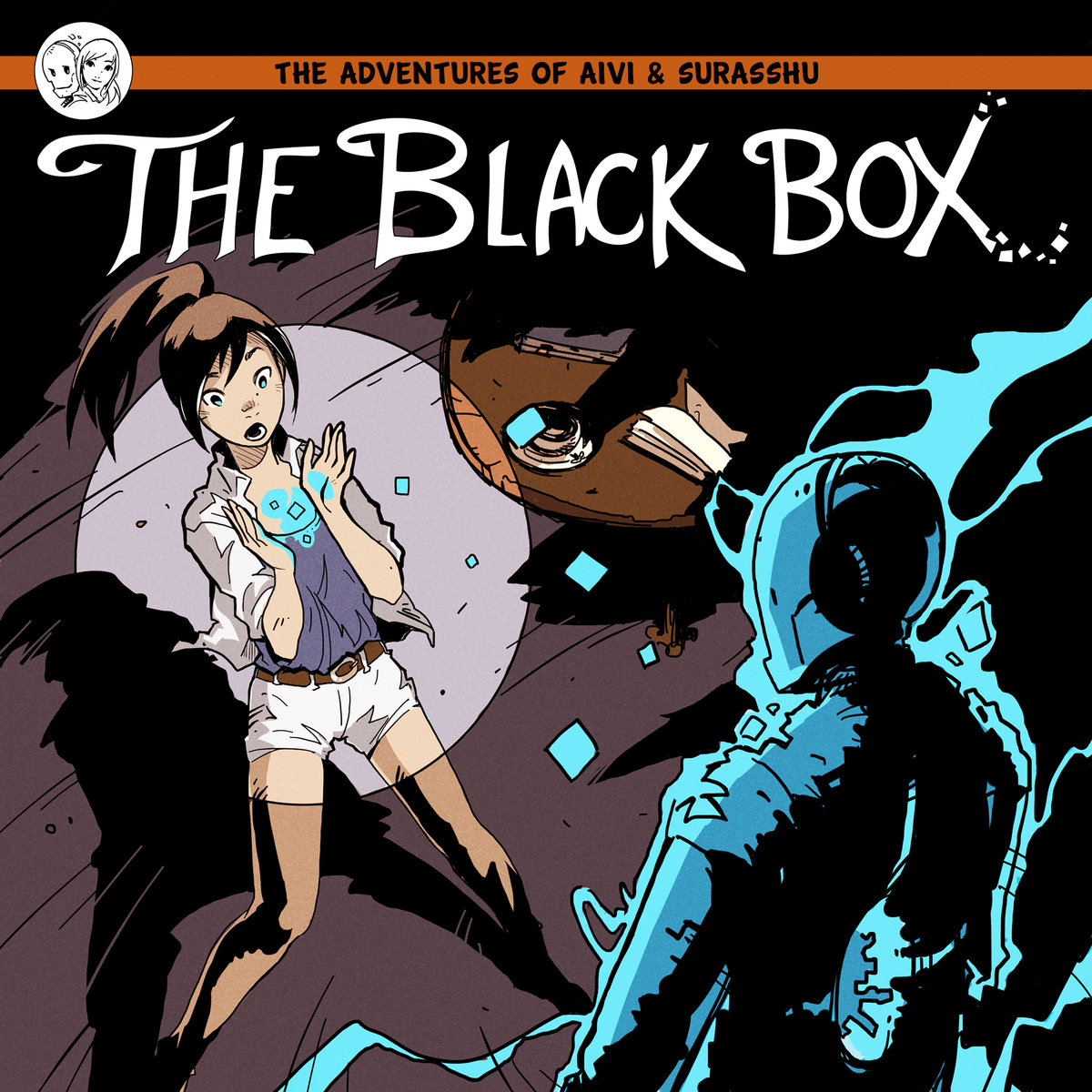

aivi & surasshu made their debut as a team with their album “The Black Box”. Cover art by Diana Jakobsson.

Our musical process varies from song to song. Sometimes he programs the drums and I write the melodic parts. Sometimes I come up with the song structure and he fills out the arrangement. Sometimes we lean into our unique specialties, like with our piano/chiptune duets. And sometimes that disaster synergy strikes. But even though we both have our own strengths, we make a conscious effort not to shoehorn each other into roles. I want to continue growing as a musician, and I want the same for surasshu.

How did you end up mixing traditional and digital sounds, like fusing piano with chiptunes? Did that come solely from the partnership with surasshu? What attracts you to that combination of musical styles?

Mainly, I love how it sounds! I started combining acoustic and electronic sounds before I met surasshu, influenced by my hybrid cultural identity and my hybrid musical background.

Culturally, I grew up a bit of a mess: my parents are refugees from Vietnam, but I’m American-born, and we lived in Thailand during my childhood. For a time, my ethnicity, nationality, and country of residence all didn’t match. I didn’t feel like I fit anywhere.

Musically, I had mixed skills in both classical piano and MIDI sequencing, so I didn’t know whether to consider myself an acoustic or electronic musician. Whenever I immersed myself in one thing, my heart missed another thing. It made sense to combine everything together, to make my own kind of music and be my own kind of person.

Promotional illustration for aivi & surasshu by Diana Jakobsson.

I’ve realized now that a lot of people feel isolated like that, and it’s motivated me to come up with new language for my work. Recently, surasshu and I started calling our music and the music of our colleagues “digital fusion”: music that combines elements from various genres (such as jazz, classical, prog, funk) together with computer music genres (such as classic video game music, keyboard demos) and features solos or other parts of the music programmed via computer software.

After I started working with surasshu, the acoustic/electronic dichotomy in my songs became less about me and more about the joy of conversing with someone else. What I love most about the combination of piano and chiptune are that both are solo instruments that can carry full arrangements on their own. They don’t really need each other. So it makes for interesting and animated duets! I think they’re a good match for each other.

What is it like working with other musicians outside of surasshu, like the collaboration with rapper Sammus on Ikenfell, and with The Consouls on Cryamore? Did you recruit them for each project?

Sammus is my favorite rapper, so it was a dream to collaborate with her on “Paint the Future” for Ikenfell. I pitched the idea of writing a song based on the colors of the rainbow, and she wrote the lyrics and rapped and sang over the instrumental that surasshu and I composed. My heart was ready to burst when I heard her line, “Sometimes I’m feeling green with envy of a boy or girl or enby.”

Zorsy is a jazz keyboard player and one of my dearest friends. I feel inspired every time we talk about music theory together. I showed Zorsy my melody for “Lil’ Miss Ostentatious” from Cryamore and asked for his advice on composing for brass section. He arranged the brass parts for my song and set up a recording session with his band, The Consouls. I’ve since incorporated the brass advice that he gave me into my piano compositions.

Both of those songs turned out better than I could’ve dreamed of because of collaboration. I respect both Sammus and Zorsy immensely and felt very honored to have worked with them.

Cover art by Cryamore developer Rob Porter for “Lil’ Miss Ostentatious (Bliss’ Theme).”

When you score a game, how involved is the rest of that game’s development team? Do they have a lot of requests for what they want the music to be, or do they leave more of the music’s creative direction to you?

The teams that I’m working with all approached me and surasshu for our musical style, so we get a lot of creative freedom. I really enjoy getting to know game developers and coming up with a holistic musical direction for their game. My job is to bring out the emotional narrative of their story, and to help them build their world and characters through music, so I frequently ask for references—their favorite music, their character’s backgrounds, even their own personal backgrounds. The more details they can share about themselves, the more I can empathize and take the right musical approach. Once in a while, the influence goes the other way and they change parts of their games to fit my music! I feel really happy when I can help inspire them.

What is it like composing battle music versus more neutral music?

Battle music gets a lot of attention because many games use combat as both a core mechanic and plot device. People really look forward to battle themes, so these songs are usually stand-out: high energy, driving rhythms, emotional intensity, complex orchestration, or intentional subversions of all of those things. Battle songs can be fun to compose, but to be honest, I find them a little exhausting!

Area themes are more relaxing for me to compose because there aren’t as many expectations, so I can experiment and do more world-building without much pressure.

Cryamore art by developer Rob Porter.

Do you also work on sound effects for games, or is that normally part of surasshu’s role?

It’s surasshu’s role, but I’d like to learn.

You’ve also been creating music for Anthony Tan’s upcoming Way to the Woods. Could you talk more about that?

I’m very excited about composing for Way to the Woods because I love adventure games, and this is my first time composing for one! And there’s no combat, so I don’t have to write any battle music.

Anthony’s game is about a deer and a fawn wandering through a post-apocalyptic world. surasshu and I are composing music that’s a bit more pensive than our past work. We’re blending piano with electronic sounds and taking inspiration from nature, like drums inspired by the sound of bugs in a forest.

Way to the Woods is expected to release in 2020.

What is the difference between composing music for games versus composing music for television? How do you approach scoring an interactive and potentially non-linear game?

I think game music is similar to writing music for a theme park or sound installation. I’m not just deciding on which notes to use—I’m designing a piece of music to function within a space, where I have no control over how my audience will interact with it. From loop points, to layers that are programmed to fade in and out when the player moves around the map—there are so many things to consider when writing a piece of game music. Composing for games is very technical, but the result is an emotional experience. I love that about the medium.

Cartoons and linear music go together like cookies and milk, since both animation and music are time-based art forms. When I first started composing for Steven Universe, I was so shocked by how quickly I could compose a scene compared to one minute of game music. We compose the music at the end of the production chain and custom fit our music to the animation. Sometimes I feel like the storyboarders and animators are co-composers because their timings guide how we compose.

How do you approach incorporating the video game influence into Steven Universe‘s soundtrack? Are there aspects about the show that remind you of video games, and is that something you try to emphasize with music?

Video game music has always been a huge, intentional influence on the show’s soundtrack. We were approached for Steven Universe because of our work as game composers! Fantasy and escapism are a big appeal in video games, and Rebecca Sugar has mentioned themes of “reverse escapism” in the show, where the Crystal Gems are enamored with “our” reality. The mundane moments on earth are the most meaningful, while the fantastical moments tend to be stressful. We often tap into our video game music roots for magical locations, Gem artifacts, and boss fights.

Our video game influences are embedded into the musical canon of Steven Universe. Something that we decided with the crew early on was to incorporate the idea of interactive music into the soundtrack. We assigned different instruments and sound palettes to each of the Crystal Gems. Characters walk on screen with their music, and when they leave, they take their music with them. When Steven and the Gems are all together on screen, their instruments form a jazz ensemble. We got this idea from classic video games like Super Mario World. When Mario rides on Yoshi, percussion enters the music, and when he dismounts Yoshi, the percussion fades away.

We implemented another interactive music-based idea through the end credits theme, “Love Like You.” The song started off as a piano solo, and every few episodes, we secretly added a new instrument to the music. By the season finale, the music blossomed into a full band with a singer.

Have you ever assigned specific instruments and sound palettes to characters in games, like you do with characters in Steven Universe?

I haven’t assigned instruments to characters in games the way we’ve done with Steven Universe, but I enjoy doing it for area themes. For example, in Cryamore, guitar and tambourine belong to the river, trumpets and snare drums belong to the fiery mountains, clarinet and choir belong to the forest—and all of the areas are unified by piano and chiptune. I once explained this to the Cryamore team, and one of the artists remarked, “See, what she does in her music is what we do with color palettes in our illustration.” Since then, I adopted the words “sound palette” to describe my selection of instruments.

Developmental art from Cryamore.

Are there differences between composing for indie game developers versus composing for major companies like Cartoon Network and Google?

Big companies have more resources and employees to aid them through the production process. You’re a little cog in a big machine, but the projects you work on have a good chance of being completed.

Indie game teams are more like little families, but the development process is often harsh for indie developers because they don’t have enough resources. They also don’t have the same protective buffer between themselves and their audience as creators working in big companies do. It’s heartbreaking to see how stressful indie game development can be. Please be kind and supportive of indie developers!

Thank you for that show of support and for taking the time to chat with us about your work.

“The Black Box” was the album debut of aivi & surasshu as a team. Released in 2013, it featured eight original tracks and three covers, including their rendition of Yoshihito Yano’s “Lonely Rolling Star” from Katamari Damacy.

“The whole album captures a jazzy, melody-obsessed video-game pastiche,” said Kotaku Splitscreen co-host Kirk Hamilton in a review.

With a fusion of piano and chiptune under the influence of video games, “The Black Box” truly serves as an introduction to the work that aivi & surasshu specialize in today.

The album also comes with imagery and a downloadable comic depicting fantastical versions of its composers—Tran as an archaeologist represented by the sound of piano, and surasshu as an excavated robot embodied in a chiptune beat. Fittingly enough, it sounds like “The Black Box” could make for an interesting game too.