A game couldn’t be a classic adventure title if it didn’t have you working for every possible opportunity just to obtain a bloody wallet from a homeless bloke on the street. Although this sounds like a total dick move, it’s actually a thing I had to do in Thimbleweed Park. One time, I even tried to combine sticky tape with an empty can of tuna fish. (In retrospect, I have no idea what I was thinking.)

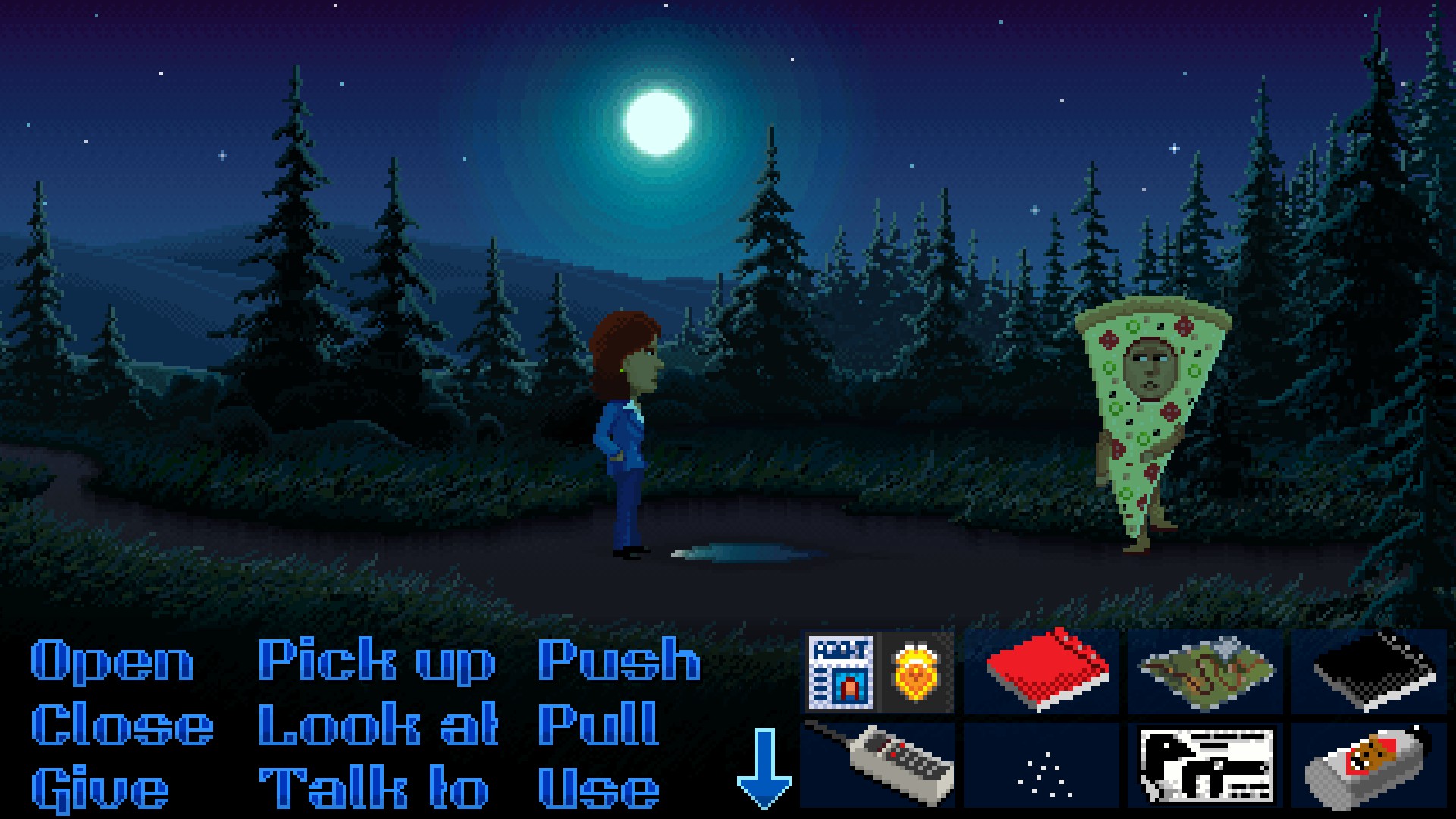

It goes without saying that Thimbleweed Park is a special gem. Unlike most modern adventure games, it SCUMMs you with verbs at every corner. All the while dazzling your glorious HD monitor with big pixels, almost identical to 1984’s cult classic, Maniac Mansion. It’s a passion project for Ron Gilbert, Gary Winnick, and company. That much becomes crystal clear as soon as the first line of dialogue appears on screen. Jokes and obscure puzzles galore, Thimbleweed Park brings back classic adventure games with a bang.

Coming Prepared

All of this is thanks to a more than successful Kickstarter campaign which got funded for $626,250 at the end of 2014. Since then, Thimbleweed Park has had a rather stable development cycle. All of which has been detailed by a stupidly active blog riddled with podcasts, technical explorations, and surprisingly honest and transparent progress updates. Take your time and sift through the posts and you’ll find stuff like a full budget breakdown, or a detailed-enough-but-not-so-much-that-it-would-bore-you-to-sleep description of how the game handles multi-character dialogue and language translation.

As Ron Gilbert himself has noted in some interviews in the past, it’s a very different way of development. Especially when compared to the mostly ‘behind closed doors’ development of culprits like The Secret of Monkey Island. Now, thanks to countless posts and podcasts, we know that the Thimbleweed Park team grew from 2 to roughly 8 people. All working remotely from around the globe. This includes David Fox (co-designer of Maniac Mansion and creator of Zak McKracken) and Mark Ferrari (the background artist behind The Secret of Monkey Island).

This increase in size is quite normal considering the campaign raised almost twice its original goal. More importantly, the game has improved drastically since its campaign pitch – both from a technical and visual standpoint. The initial few months of development basically involved Ron Gilbert coding away and creating a 2D point & click engine from scratch. Just so the team could have full reign later, when devising puzzles of utmost perfection and diabolical ingenuity.

(The engine’s back-end part was apparently named “Grumpy”, while the graphical portion ended up being called “Wimpy”. You can read about the reasoning here.)

As a result, Thimbleweed Park actually feels like a pimped-out, modern version of an adventure game from the early 90s. The lighting work is most noticeable. Characters are illuminated in different shades as they step under street lamps or look towards the sunset. Movement, switching between protagonists, and parallax scrolling are also smooth as butter. This makes the overall experience of rushing from point A to point B just to pick up a damned piece of toilet paper extremely enjoyable and non-intrusive.

The difference between early and current screenshots is also quite staggering. For example, here’s how a hotel area looks now compared to late 2014:

SCUMM Your Way To Victory

But what about the puzzles? Can you choose between countless meaningless, yet charmingly funny responses? Are there glorious puns? Are there any monkey wrenches?

The answers to these questions are yes, yes (there are so many puns you’ll feel punstoppable) and no (thankfully). Simply put, Thimbleweed Park is a game which isn’t afraid to give you a hard time. Stated more than once in the Kickstarter, the developers delivered on this initial promise with no exceptions.

As someone who’s not the greatest at point & clicks but also stubborn enough to brute force their way through, most of my adventures involved me slowly poking my way through a complex set of intertwined puzzles. In the beginning, there was a dead body in a puddle of water. Then, an oddly desolate city with freakishly cheery citizens unveiled a place filled with vacuum tube-powered machinery, abandoned stores. All set against the mysterious presence of some man called Chuck. The puzzles increased tenfold, new playable characters started appearing out of nowhere, and I had no idea what to do.

Often, I found myself in a cycle of grasping at straws for hints then jumping in excitement at potential solutions. Particularly notable in the case of puzzles involving feeding a hamster in a cupboard and microwaving a piece of paper. Those might sound like totally nonsensical interactions, but their presence also gives Thimbleweed Park its old-time adventure game charm – a major factor which brought the game so much success on Kickstarter.

And as someone who’s experienced a fair bit of point & clicks from the past, I was having a ton fun. For every obscure puzzle solution, there was a snarky comment from one of the detective protagonists. For every life-threatening situation, I got a fourth-wall-breaking joke bashing Sierra Entertainment for having fail states in their games. Once you get used to the puzzles, you realize they’re mostly identical to the way you remember them from games like The Secret of Monkey Island – stupendously logical, at least in hindsight.

Once again, all of this goes back to Ron Gilbert and Gary Winnick wanting to make a game that really feels like it was released in 1990. Only this time it’s somewhat revitalized, with elements such as character swapping, vague objective lists hidden in items, and impromptu fast travelling giving the formula a bit of a fresh perspective. For example, I found myself changing characters all the time just so I could talk to the same NPC on the off-chance of finding some alternate dialogue options. You learn about how the world works by interacting with it, either by getting creative with the SCUMM system of verbs or simply by talking to people.

There still are moments when all you do is spam verbs in desperation, but that’s mostly a by-product of the actual genre. And for the amount of stuff you can do in the game’s substantially sized world, it’s actually tough to find yourself facing an insurmountable task.

Where’s My Loot?

Speaking of insurmountable tasks, I dare you to go through the backer mentions without spending a few days laughing hysterically. I was more than amazed when I found a library in a mansion containing about a thousand two-page books. Each one written exclusively by supporters of the Kickstarter. There’s also a usable phone which allows you to ring countless pre-set “currently not available” voice messages submitted by backers. Apparently, both features came to life spontaneously thanks to the awesomely active Thimbleweed Park blog. For example, here’s a post containing more than 1000 responses. Some of them are quite the laugh.

When it comes to physical rewards, the soundtracks and printable CD/cassette tape sleeves were already shipped and will arrive to the appropriate backers soon. All remaining physical rewards will be sent out in the coming months. It’s also worth noting that Android and iOS versions of Thimbleweed Park have yet to be released. Apart from that, all other stretch goals are implemented with no issues whatsoever.

Sadly, a Commodore 64 with dual 1541 floppy drives wasn’t part of the backer-exclusive Kickstarter rewards.

Final Act

With that out of the way, I think it’s safe to say that Thimbleweed Park is a true crowdfunding success. The decision to keep all Kickstarter updates to the bare minimum and switch to a more open, in-depth blogging approach of communication seems to have been the right decision. Judging by the active community the game’s developed over the past few years. Numerous podcasts functioning as stand-up meetings for the development team also offered a rarely seen insider peek into the nitty gritty of making an adventure game with a team scattered across the globe.

This honesty is directly translated into the game, where you find just what you signed up for back in December 2014 – a charming, witty, and nostalgic point & click that hits all the right notes. If you’re a fan of classic adventure games who doesn’t mind a bit of challenge, Thimbleweed Park is a game you’ll absolutely adore.

Now, here are some top-secret tips and tricks that will make your life easier, and perhaps 100 times happier:

- To avoid being like me and listening to the same conversations a dozen times, pressing “.” lets you skip dialogue. For some reason, there isn’t a clear in-game indication of that being a thing. (ed: It’s been added to the help screen)

- The game’s video settings contain the vitally important option of choosing the orientation of a toilet paper roll. (It goes without saying, over > under.)

- Only voodoo-loving, undead bearded pirates use guides when playing adventure games.

[…] Having raised €10,717 on Kickstarter to bring his Monty Python-esque adventure game to life, Jean-Baptiste has kept backers updated semi-regularly. His initial plan to focus on the puzzles and global experience of Lancelot’s Hangover before polishing mechanics hit a bit of a snag recently, after the release of Terrible Toybox’s Thimbleweed Park. […]