The first time I saw YIIK: A Postmodern RPG, I felt excited and a little worried. I’ve previously mentioned both my love of the Earthbound/Mother series and severe doubt that anyone could list it as a reference and make something worthy of mentioning its name. After Undertale and a few other titles, I’ve softened up, but I’m saying that so you can understand my trepidation. Earthbound/Mother is a series very near and dear to my heart and helped me appreciate non-mainstream gaming. YIIK: A Postmodern RPG immediately looks like it fits the bill, oozing personality and style. My only concern is that the style may not appeal to me.

Head Games

Almost as soon as the game starts you’ll get that Earthbound feel: little podunk town in 90s America, catchy music, calling someone on the phone to save your game, the missing dad, digging through garbage for items, people asking for money and telling you to come back later… but what’s really nice, especially after having lived in Japan, is that this feels more possible. JRPGs have kids walking around doing all these things because Japanese kids actually can do those things. They travel in small groups without adults and do things we associate with adult life: buy our own food, take the bus, help people out in our community, greet people you see around town, sometimes come home really late, though not so much of the breaking and entering.

To have an RPG match a favorite JRPG setting but have adult characters is really good for immersion. So is the fact that you’ve boomeranged back home after college, have your parents still asking that you be home for dinner as people who didn’t leave home walk with you down memory lane. That’s not my situation, but close to it, and I know a few people like that, so it hits home.

However, this is also where things start to unravel. The main character, Alex, is so hipster it’s embarrassing. While legend tells that there were hipsters at this point in time, I did an informal poll of people between the ages of 25-35 on the east and west coast of America. These people were of various ethnicities, countries of origin, and other backgrounds, and none of us feel like we noticed hipsters until the 2000s/2010s. While they may technically have been around, hipsters weren’t a subculture clearly recognized by the mainstream yet. It feels like an anachronism, like having a Nirvana appear in That ’70s Show.

This is where things start to get meta. There’s a self-awareness to the game, not in an Undertale “I know you reset the game!” kind of way, but in a 90s JRPG “I hear press B lets you dash, but I don’t know what a B is!” kind of way. The game may be advertised as a Postmodern RPG, but surrealism stands out much more, and knowing that postmodernism loves irony and skepticism makes the surrealism feel like a distraction, there to throw you off from deeper themes that may or may not be developing around you.

In pieces

I admit, that all may sound I’m overthinking the demo, but it’s important because YIIK is not a traditional RPG. It breaks a lot of conventions. It’s a more modern setting. You’re playing an adult. Your parents are divorced. You’re a loser, not the chosen one. Puzzle hints are very subtle, not giant sparkles. The turn based attacks use mini-game mechanics, like having to tap on Alex’s vinyl record on the colored points to build combos as it spins.

My demo was outdoors with a glare, and Brian Kwek from Ysbryd had to point out a few things I kept passing up due to the onscreen glare, showing that players really need to pay attention to details. It’s not that the game lacks them, as Alex gets a red exclamation point whenever he can interact with something. However, the puzzles also often don’t have solutions you might expect. For example, you find “Panda” early on in the game. Panda is a sentient “tool” that seems mostly meant for activating heavy switches. However, he can also be used to block monster paths and to step on while crossing gaps. I learn this in an area that’s filled with switches that create walkways, but the last gap has no switch: Panda, the tool for unlocking the previous paths, is essentially my final bridge. These kinds of puzzles feel less RPG and more Adventure game.

But perhaps the biggest difference is the use of first-person narration in a game that feels like it has a linear story. Alex essentially talks to himself, or maybe you, the player. Part of it may be because I’m used to silent protagonists for these kinds of games, or maybe it’s the fully voice acted audio popping up only when the main story’s involved, not during exploration. I know when I’m playing a “choose your own adventure” type game, first person perspective is fine, but with a linear story, it gets weird.

That may seem off topic, but the game plays with perspective a lot. A few characters narrate their thoughts like the disturbed people you meet in the rough part of town, though at least one doesn’t seem entirely human, so it gets a pass. Something is happening beneath the game’s surface though, and I mentioned this to Kwek. I admitted that I don’t really like Alex, that I suspect certain artistic “mistakes” may be intentionally misleading or oddly crafted, especially because they’re coming from Alex and I suspect that he is going to change and grow through the game, possibly necessitating the immature feeling dialogue so it can mature with him.

Kwek seemed to struggle with the feedback. I’m used to giving direct criticism like this and having people explain why they made a choice, or ask me to explain my idea in a different way so they can understand me better, but not Kwek. All he does is confirm that Alex will be changing through the story. I’m both relieved and frustrated, especially since the demo is long. I played for nearly fifty minutes and had to pry myself away to get started on my drive home.

While playing the demo, I admit to myself that the narrative strategy is an interesting idea, but it’s also unsettling and, frankly, wrong feeling, like an example story a creative writing teacher might show you so you avoid making that person’s mistakes. Times where the dialogue between two characters suddenly shifts perspective and style into something I’d expect to read in a teenager’s journal, made worse by hipster references that feel overly crafted, make me want to move through the game faster. It is thoroughly difficult to manage, but again, something is happening here, and the surrealism keeps bringing it home.

Girl on the moon

During the demo, you’ll find yourself in a strange space (literally) and in a rather unbelievable scene while looking for a cat. You find the cat’s owner first, and Sammy is also not what I’d call likable, but slightly intriguing. Alex, naturally, feels the same, but while he’s cool with climbing up a pyramid and poking a living eye, he freaks out because Sammy doesn’t know what an elevator is, creating quite a Kafka-esque moment with weirdness abound and our hapless hero focusing on a small, inane detail.

The all seeing eye you all may know from the American dollar bill keeps popping up. Alex pokes it like it’s nothing, but it shows up on a later puzzle, but Alex doesn’t pipe in with some kind of not-as-smart-as-he-thinks-he-is comment. He’s too concerned with finding a cat with a too descriptive appearance that took his mother’s shopping list before bumping into a girl who’s both ignorant of his culture but possibly on the same wavelength, as both somehow see Salvador Dali in the cat’s face without Sammy actually knowing who the surrealist artist is.

And again, it immediately feels like a distraction. The whole situation is too weird to ignore, which I love as a gamer but am infuriated with as someone who himself isn’t as smart as he thinks he is. It’s not just that the game calls itself postmodern, but it’s these symbols– carefully chosen names, mythological icons, artists– that keep popping up, feeling half-baked and twisted, then seemingly discarded only to come back. The pessimist in me wants to declare it all hipster garbage, but the critic in me keeps grabbing threads and trying to untangle what’s before me.

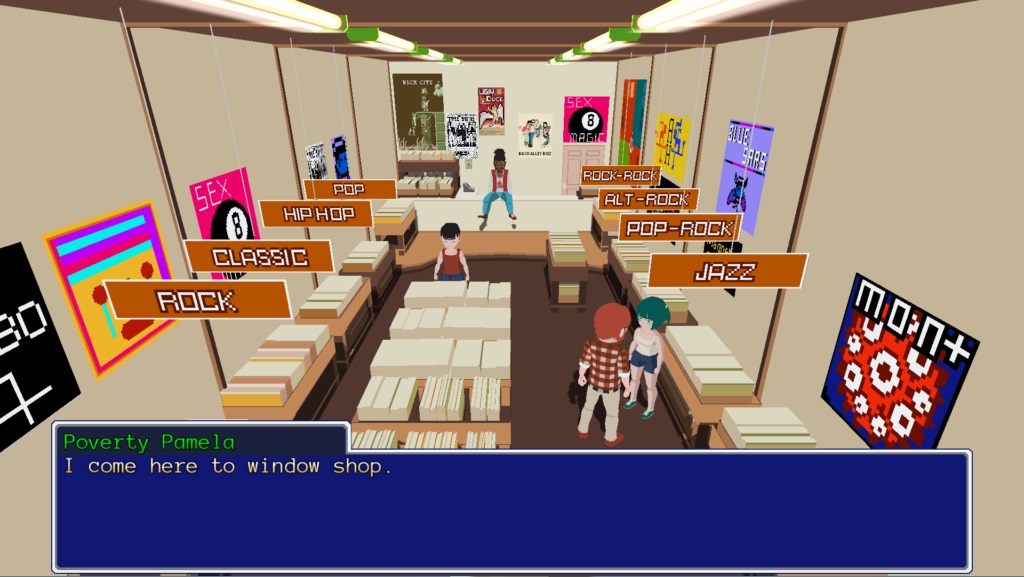

I’m digging the mini-game combat, the cool music, the colorful surreal art, the little touches like searching the couch for change, and the 90s nostalgia of the internet being a cool new tool that’s slowly killing physical distribution techniques and goods. I am really digging a lot of the game when I’m in the moment, but when weird girls or pretentious dialogue rear its ugly head, I start getting lost in my own head. Even as I write this, I question if I’m now competing with the game’s sense of potential grandeur, or if its just the teacher in me trying to break this all down for an audience that I assume is as eager to understand as I am.

Jukebox Hero

There was a lot packed into my demo of YIIK: A Postmodern RPG. Alex and Sammy, for me, aren’t very likable but are relatable. Alex comes across as the kind of guy you’d still meet these days, but as his hipster cred requires him to do things like praise the superiority of vinyl records without someone there to hear him, you may not necessarily like him. He’s young and full of himself despite obviously having boomeranged back home, something I’m sure many of us have experience with, if not opinions of the people who do. Like any awkward teen or adult, he ruins the moment by saying too much or too little just at the wrong time. Like YIIK, he has some obvious artistic influences, which help give the game its personality but also make me want tell him to shut up and live in the moment because his reflective nature and monologuing clearly rubbed off on me.

But YIIK has so much going for it, not just in immersion that makes Alex feel annoyingly real, but with mechanics that remind you of why we look to indie games for innovation. The whole thing reminds me a bit of Gundam, in that I think the world’s really interesting, but I only follow the characters to see how the world will shape them, or how they may shape it. The surrealism is visceral and probably what will get people to invest in the world. I’m just hoping Alex’s maturity and the game’s narration will move at a quick enough pace to keep players’ attention and pay off in the end.