As Halloween approaches, people may seek out different flavors of fictional horror, including video games. Accounting+ can provide a spooky time; played out in a VR game that successfully and unnervingly immerses you into frenetic reality-jumping.

It’s a game that reflects well on the intentions and spirit of one of its studios, Crows Crows Crows—and its co-founder William Pugh, also co-designer of The Stanley Parable.

Upgrading a Game

Accounting+ is actually the updated version of Accounting that Crows Crows Crows and Squanchtendo—a studio started up by Rick and Morty co-creator Justin Roiland and now called Squanch Games—first released in 2016.

According to the game’s website, Accounting started at a game jam that consisted of William Pugh, Crows Crows Crows co-founder Dominik Johann (also art and design on Minit), and Justin Roiland.

Accounting would go on to win VR NOW’s Art Award and Deutscher Entwicklerpreis’ VR Special Award in 2016.

Accounting+ was recently recognized as a finalist at IndieCade 2018, described as a nightmarish adventure comedy on the festival’s website.

Jumping Through Layers of VR

Taking place in the Santa Monica College Center for Media and Design, IndieCade showcased festival nominees on the second floor of one of the school’s buildings, including Crows Crows Crows’ VR experience.

William Pugh, there to help demo the game, said that Accounting+ was partly made to do something more interesting with VR. He felt that a lot of VR before focused heavily on showcasing the technology above other possible aspects.

“The opportunity was in VR,” said Pugh. He further described his partnership with Roiland; they got in touch, talked about game development, and considered collaborating together.

He said Roiland expressed interest in VR, and at a time when his work was less Rick and Morty-focused. Pugh commented that ultimately Accounting+ has a lot of Roiland’s influence (and a lot of his acting, with Roiland voicing characters in the game).

Pugh shared that the project started with a couple of jokes; teleporting to different worlds; and simple, still characters with drawn-on faces. He described it as more like a flip book.

According to Pugh, making Accounting+ involved working with audio before working on other aspects like the game engine, it was “more audio-driven or devised more like a radio play.” He could get an idea of what the game would sound like before anything else. A lot of improv dialogue went into Accounting+.

Doing this sort of pre-production work became a guiding principle, with the goal to “treat game design more like the storyboarding process,” something Pugh said was inspired by Roiland’s work in TV animation.

In that field, storyboarding is often used as a planning tool for creating episodes. (It’s not exclusive to TV animation; Gamasutra reported that game designer Tim Schafer storyboarded the adventure game Grim Fandango.)

“You want to get it right before you animate a bunch of characters,” remarked Pugh.

This also helped Pugh figure out how to get tone right. He considers “tone in a broad sense—story, cinematography,” etc. Pugh said that tone is as important as the rest of game development, that it’s about “prototyping the feel of a story,” not just systems.

Pugh described Accounting+ as more of a closed loop in the beginning. But he said his favorite aspect of The Stanely Parable had been how open it felt, like it could be explored.

And so Accounting+ became more open, with many secrets to explore. He mentioned that the game even has a secret water park level.

“A game is only as good as its secrets,” said Pugh.

A Post-Accounting Life

Although storyboarding was an inspiration for more planning in the development process, Pugh also describes the current Accounting+ as an accumulation of about 2 years of improv, “building stuff out of stuff.”

But Pugh said Crows Crows Crows’ next project will be the opposite, more tightly controlled, “more precisely done.” He said that everything will be looked at carefully, from style of comedy to how it’s written.

“Feels good to be changing things so often,” Pugh said.

Pugh shared that there are actually two projects coming up on his studio’s docket, and that they are both exciting to make and release.

“One of them is looking to the past,” Pugh said, starting to describe the future projects. “And the other looks into the very deep past.”

Ornithological Origins

According to the Guardian, Pugh first became interested in video games when he played a Nintendo 64 at the hospital. After a short time attending Leeds College of Art, he left to start making video games, teaching himself by making levels for other games like Left 4 Dead and Team Fortress 2. Later he worked with Davey Wreden to remake Wreden’s The Stanley Parable, which had first been done as a Half-Life 2 mod.

The Stanley Parable (Davey Wreden and William Pugh, 2013).

Destructoid reported that 2 years after The Stanely Parable remake, Pugh started his own studio, Crows Crows Crows, with Johann.

Crows Crows Crows’ first game was Dr. Langeskov, The Tiger, and The Terribly Cursed Emerald: A Whirlwind Heist, which focused on giving players a meta experience by having them work backstage on the titular game, as if it were a theater production.

Pugh said that after working together for a year on that project, a public release was near, and he realized that there were too many people’s names to list as developers behind the title.

It was better to come up with a studio name that would represent them all instead.

Dr. Langeskov, The Tiger, and The Terribly Cursed Emerald: A Whirlwind Heist (Crows Crows Crows, 2015).

Pugh said it made sense to start branding themselves. But he also knew it was something to think about, saying that the name would likely be with them for the rest of their lives, and something they would be repeatedly typing out.

According to Pugh, “10,000 Bees” was the first working title. The team kept thinking. Pugh said they didn’t want a generic name. They wanted to stand out.

Eventually Johann just suggested “Crows crows crows.” The response? Immediate acceptance, mainly because it had reached a point where they couldn’t think of anything else.

Pugh said Crow Crows Crows’ Discord has all sorts of fan theories about the meaning of the studio’s name.

Even the UK-based publication Market for Computer & Video Games (MCV) theorized that the studio website’s 2015 message, “Expected lifetime: 18 months,” roughly coinciding with a crow’s life span indicated that the team could be a temporary cooperative effort. (After releasing multiple games, Crows Crows Crows has soundly debunked that theory.)

The studio name worked out for Pugh, who had grown up in the countryside, and liked the imagery there. He said that wasn’t the reason Crows Crows Crows was selected, but it was a bonus.

Going Down the Rabbit Hole Again and Again

After speaking with Pugh, he invited me to try Accounting+.

The Crows Crows Crows demo booth was in a relatively crowded room, shared with other IndieCade finalists, including Just Shapes & Beats, a multiplayer bullet hell that contributed a noisy but cheerful mix of the game’s own music and sounds from entertained players.

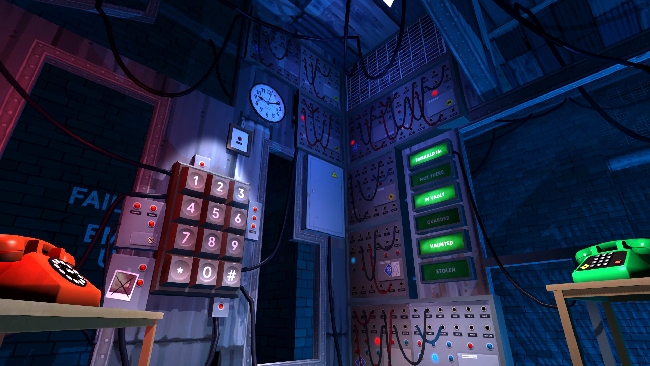

But that all went away once the VR headset was on, and I felt fully immersed in the surrounding visuals and the new audio that filled my ears, that largely quieted the outside world. I instinctively reached forward for things that literally weren’t there, and had to remind myself to not do that.

Accounting+ had what I found to be an interesting physical mechanic—there were buttons on the controls given to me that I could push, so that the in-game vision would rotate without me actually moving.

It seemed like it served multiple objectives: like it was meant to ensure I could always navigate the game space, and meant to try to stop me from literally moving around too much and potentially knocking into real things.

But I got so immersed, I constantly forgot that I could move with the press of a button, and just kept physically moving and accidentally bumping into real-life things, like what I assumed was the game’s physical set-up. It became an equally constant struggle to remind myself that I didn’t actually have to move around so much with my own body.

The game started off with an Inception twist that remained consistent throughout the demo and proved integral: I put on an in-game VR headset, and was teleported to a new place.

Although the graphics in Accounting+ were stylized and cartoony, I grew unsettled and unnerved with the world they were used to bring to life. I keenly felt the “horror” listed in the game’s description more than anything else.

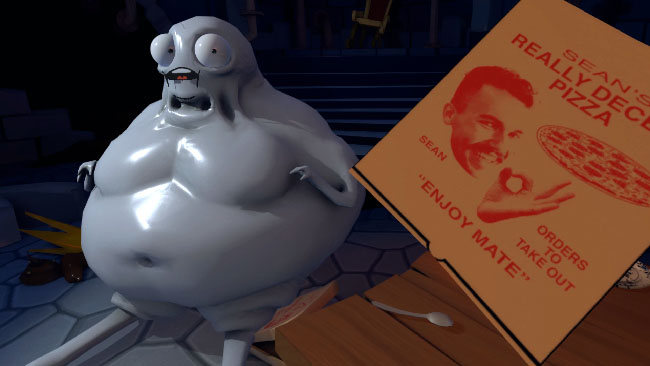

The NPC characters were cartoony and some were even anthropomorphized critters, but more often than not they berated me and were otherwise aggressive, or unnerving in other ways.

They never touched my in-game and my mostly unseen avatar, but their harsh tone often set me on edge. Words alone triggered my flight response.

I was made keenly aware of my isolation within the VR space. There were no allies here in the game.

Even the friendliest NPC was unsettling. He did nothing—but I was alone in a dark dungeon with him, which held a mess of a dining table that included a large knife. And this NPC looked grotesque, feeling intimidatingly larger than me.

He did nothing aggressive, but the whole picture he was a part of made me distrust the whole situation. He even started to sound too nice, as if he were covering something up, and plotting against me.

Looking back, I appreciate better what Pugh said about the emphasis on audio and dialogue in making the game. What I could hear in Accounting+ was key in swallowing up my imagination and slowly filling me with dread.

For example, an in-game phone call I picked up wormed its way into my ears, the callers’ increasing anxiety over the right character failing to respond to them setting me on edge, especially since it was dawning on me that I had killed who they wished to speak to.

Context like that made the NPCs more disturbing. At first, they would overreact over nothing, like something as ultimately meaningless as turning off the radio.

But then they started reacting more within reason, such as that frantic call. As mentioned above, the game compelled me to murder for the sake of moving on and not getting stuck in an area. Another NPC eventually put me on trial for it. He was aggressive, but for good reason, and now some guilt mingled with my dread.

The VR of Accounting+ really sucked me in.

I talked about how the game compelled me to murder. It also compelled me to pour acid on myself, bend down to get beheaded by a guillotine, and instigate a fiery car crash while I was a passenger.

As far as I could tell, I could not progress through the game without committing violence against others, and against myself. Several times I could only teleport to different places in the game by “dying” somehow. (The relatively more benign alternative was finding another in-game VR headset to teleport me, like at the demo’s start.)

Though it was all VR, I felt unsettled by the whole thing. My imagination was running away with me.

But looking back, it feels like a harsh deconstruction of common gameplay mechanics. Players killing other characters or enemies. The player gets killed, but returns, and can be even taken to different places when they regenerate.

Those mechanics become more unsettling when Accounting+ executes you for killing a character, or when it makes you submit to a guillotine to escape the place you’re currently stuck in.

Accounting+ largely immersed me in what felt like a downward spiral of a trap. I started to feel like I was meant to take increasingly desperate measures to escape my predicament of being forced to jump realities, but each attempt only made me fall further down the rabbit hole, and circle back around into heightening my desperation.

An NPC character became very direct and meta toward the end of the demo, essentially yelling, “It’s VR, none of this matters!” It actually wasn’t much comfort, especially since I ended up having to shoot that character later.

Of course, it practically doesn’t matter. No actual harm is done in VR, or in any other game.

But in my head, it felt like it did matter, if only in terms of momentary discomfort. I wasn’t necessarily having fun, but the game’s VR had succeeded in immersing me, and in following through on its nightmarish description.

When the Crows Crows Crows team stopped me, saying that they felt like I had played through a demo with a complete arc, I felt relief.

The music and sounds of entertained players from Just Shapes & Beats was still going on, and was welcome to my ears.

After that, I needed a break. Accounting+ still lingered.

And yet with Halloween around the corner, I knew the game was something I would recommend for a seasonal scare.